If we’re going to generalize (and of course we are), the Obama administration split politically conscious leftists into two camps: the complacent and the disillusioned. The former felt a sense of euphoria with every victory in the name of social progress, while the latter felt the fall of the heavy shadows under every shining accomplishment. The mold is always the same: pick an Obama-era success story, then shake it and see the fallout.

For every state that recognized same-gender marriages, LGBT folk continued to face home, workplace, and public discrimination and feared for safety. For every person who was eligible for comprehensive health care without being denied for a pre-existing condition, another would be denied access to basic health care based on low income (and if state welfare wouldn’t pick up the case, a code to avoid tax penalty would serve a conciliation). For every soldier withdrawn from Iraq, drones covertly surveyed and struck other “problem” areas.

So on and so on and so on.

The iconic features of art in what may be referred to tongue-in-cheek (though I hope to g-d not in my lifetime) as “the dawning of the age of millennials” reflected this anxious dualism. Palatably pretty but dismal and dangerous singer-songwriters such as Lana Del Rey, Melanie Martinez, and Marina Diamandis cornered the airwaves. Connoisseurs and critics slammed into Banksy’s mock-up Dismaland with the tenacity of a Midwest family of five descending on the real thing (the Dismaland website seemed to have just as poor bandwidth and traffic control as the real Disney site, at the very least). The “twist” to every “provocative” horror movie that managed to claw its way into cinemas was always the same: the villain dies (maybe), the hero dies (probably), everyone dies (definitely), and the world keeps spinning. Nothing changes. That’s right, 2008 election slogan, nothing changes. Hence why every movie in the Obama administration was shot with the same regulation, g-dawful, “gritty” filters that made everything look dirty or blue—not sad, just literally blue.

On TV or in the movies, almost every character that could be identified as gender divergent or non-heterosexual would presumably be dead within the same season they were introduced, or most certainly by the end of the feature. But a conundrum: was the “kill your gays” trope a grim commentary on current events meant to shock and provoke complacent souls (particularly those of the straight, white, cisgender set) into acting on outrage, or was it a loaded message to the LGBT community, a casual reminder that a marriage license is neither a sword nor a shield? Which came first, the chicken or the egg? Does art imitate life while imitating art?

The aesthetic of the Obama age was pain, but not the bloody and raw gore of the Bush administration. This was the art the adolescents of that era created when they were told they didn’t have to worry anymore. This was a new type of subcutaneous chronic pain, which would be especially excruciating when worn with a smile. The cruel irony was that the same platforms that advocated for suicide and self-harm awareness and visible monikers for support were also converging points for self-deprecating comics or punchlines depicting hurting people hiding their hurt behind masks of mundanity (think the infamous “This is Fine” dog from KC Green’s Gunshow).

Such was the “abomination of Obama’s nation” that was lost in translation—the “do as I say, not as I do, because I didn’t mean what I said (except for the part I really meant)” neurosis that anticipates major meltdowns. Kanye’s happened to be very public, and his wasn’t the only one. An entire political party teetered dangerously on its own identity crisis over the course of the 2015/16 election cycle, and by the end of it, the Shepard Fairey Hope iconography was almost indistinguishable from the parody memes.

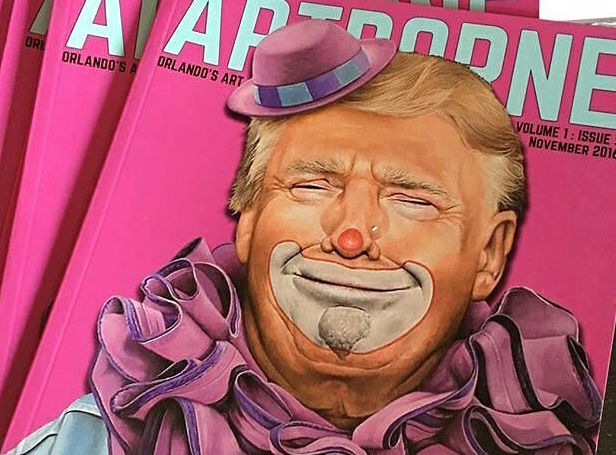

But what if there is hope for healing? What if art in the age of Trump won’t serve like art in the Obama administration? What if instead of paying backhanded compliments to complement his office, art will aspire beyond the Trump years (however few or many there may be). As the millennial demographic comes into its own after eight years of brow-beating, one would expect these adults to resemble the gruesome hostages seen in the previous generation’s gratuitous torture porn flicks. To the contrary, the seeds of prosperity have been planted and are coming into bloom.

Superficially, the plot of Get Out mirrors the plot of Obama-era shock flick Tusk: both are about men who are “foreign” houseguests to the demographic reflecting their amateur mad scientist hosts. Both films follow the protagonists’ fight for body autonomy. Both films also deliver on the promise of their titles: Tusk boasts a gruesome, bestial climax, while Get Out features a black protagonist who survives his harrowing predicament when all the real-world evidence demonstrates how he shouldn’t have.

The backlash Beauty and the Beast experienced going public with its trademark “exclusively gay moment” (patent pending) was to be expected from the folk who spend their downtime writing missives for their mommy blogs, but the fear and apprehension from the LGBT community is a trauma from the previous administration. This community hasn’t forgotten “kill your gays” in the wake of the Pulse massacre. How effective could a “gay moment” be? What could it possibly accomplish to undo years of inherited trauma? Not much, alone, but in succession with other LGBT narratives great and small? Whatever Beauty and the Beast does or doesn’t accomplish as a milemarker for gay visibility, the storyline does seize an opportunity to demonstrate how much mileage can be gained with empathy, compassion, and personal initiative to the pain we’ve burdened ourselves with in our art.

It would be disingenuous to outright predict what will change in our art culture in the Trump years, but for the first time in a long time, there is hope to see and to be seen.