When hearing the term “surrealism”, most people think of melting clocks, flying fish, or animals with unnaturally long toothpick legs. The artistic style has a reputation of being weird for the sake of being weird, but there is much more to surrealism. Victor Quino is all too familiar with rejection because of the surrealistic nature of his paintings. He is often told that his work is not sellable, and if he wants to be represented by a gallery, he has to drastically change his art.

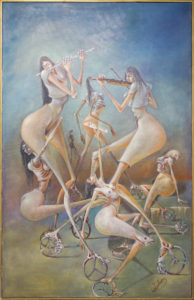

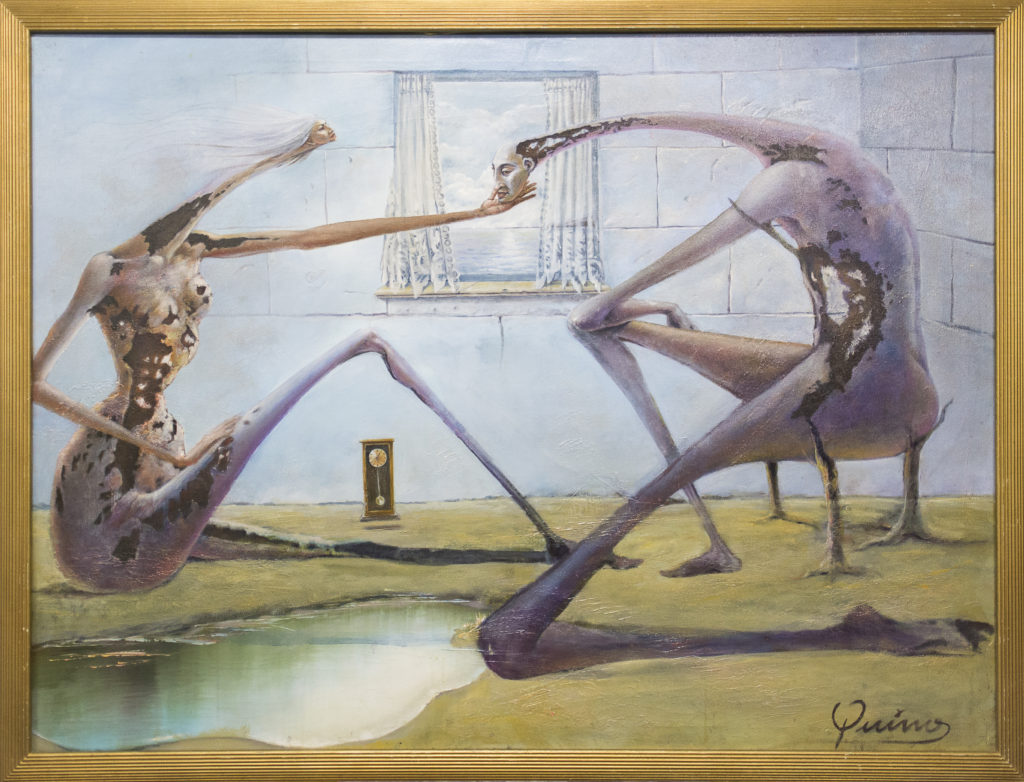

“This is my expression. I don’t want to make art for business,” Quino explains to us while we visit his studio that is filled with work from the past forty years. There is not an image of a melting clock in sight. There are, however, elongated humanesque forms with wheels attached to their feet, images of water ranging from puddles to oceans, blue skies decorated with fluffy white clouds, and lots of images of horses. You can find a horse in almost every painting in Quino’s studio. To him, the horse symbolizes “power, strength, and loyalty” and he personally identifies with the creature. Even though Quino has not spent any time around horses, they always seem to work their way into his paintings, and he often describes the horse as himself. One of his earliest works that I saw was an ink illustration of a large horse trapped inside of a tiny room. “That’s me. I’m the horse, every time,” Quino explains.

Before coming to the United States, Quino grew up and studied fine art in Peru. He showed me work from 1977, created when he was a student. His traditional drawing background surprised me when I saw his gesture drawings that he brushed off as being poorly drawn—what they showed was a classical understanding of form and light. He graduated from art school with a degree in sculpture, where he predominantly worked with metal. Quino even created metal sculptures of horses, explaining that his association and fascination is something that he always identified with. Not being taught about surrealism in school, he was only aware of the artistic style after he was exposed to the works of Gerardo Chavez in a gallery. After seeing Chavez’s work, Quino realized paintings are more free to express than sculptures so he switched mediums—“Maybe I’m in the wrong place.”

Like that large horse in the tiny room, Quino felt trapped living in Peru. In order to satisfy his personal longing for freedom, he felt that his only choice was to leave his family and travel to the United States. Boris Quino, Victor’s son, explains his father’s experience when he left Peru: “In the beginning, he didn’t know he was coming to the United States. He brought me a case of letters between him and my mother, when she was in Peru. He decided to come to the United States, and emigrated from country to country to get here. All of the letters are a reflection of him trying to break free from one place to another place.” Boris did research on his father’s life for a documentary, “Before the Lights Go Out”. The documentary, being produced by Valencia College, will tell Quino’s story and struggle.

Quino was reunited with his wife in America, but it was not easy for him to leave his family behind. His hard work and charismatic personality helped him succeed at work, even though there was a language barrier. He used his art as a way to break the ice. After creating a caricature of the owner of the printing company he worked for, he was promoted. He soon became an illustrator and landed other design-based jobs. But while he was becoming a successful American, he had family trouble back home. His father passed away, and Quino had no way of going back to Peru. Painting became a method to cope with the emotional and physical detachment he felt. He made paintings of mourning figures with distant funerals, separated by cracks in the earth.

The narrative of his early work is easier to decipher. It wasn’t until Quino let his subconscious take over his artwork that he started to create the colorful works filled with layers and hidden meanings. One of the trademarks of his paintings is his use of color. He has the ability to take otherwise bright colors and somehow make them look sad or haunting. Not all of Quino’s paintings deal with the macabre, but it is difficult for anyone to paint a cheerful scene when everything else in their life seems to be grim. He has many paintings depicting his loving wife reaching out in all directions, trying to help her independent children who insist on becoming adults. Weeping figures, solemn faces, and pools of water all symbolize the sadness that he witnessed in his wife. Quino’s work gets a reputation for being morbid or depressing, but his paintings are reflections of his emotions. The key to the surrealist style is the dreamlike state which he enters while creating his work. The paintings appear to him as he is creating them, and they often mirror his personal experiences.

In 2013, Quino had a stroke and struggled with cancer. He fought long and hard against the cancer, but lost vision in his right eye during the process. Icons from this tragic event in his life can be seen throughout his work. One recurring image is of Quino’s dog. “Morena. She protects me a lot. She is very close to me. She follows me everywhere.” Especially during chemo, she never left his side.

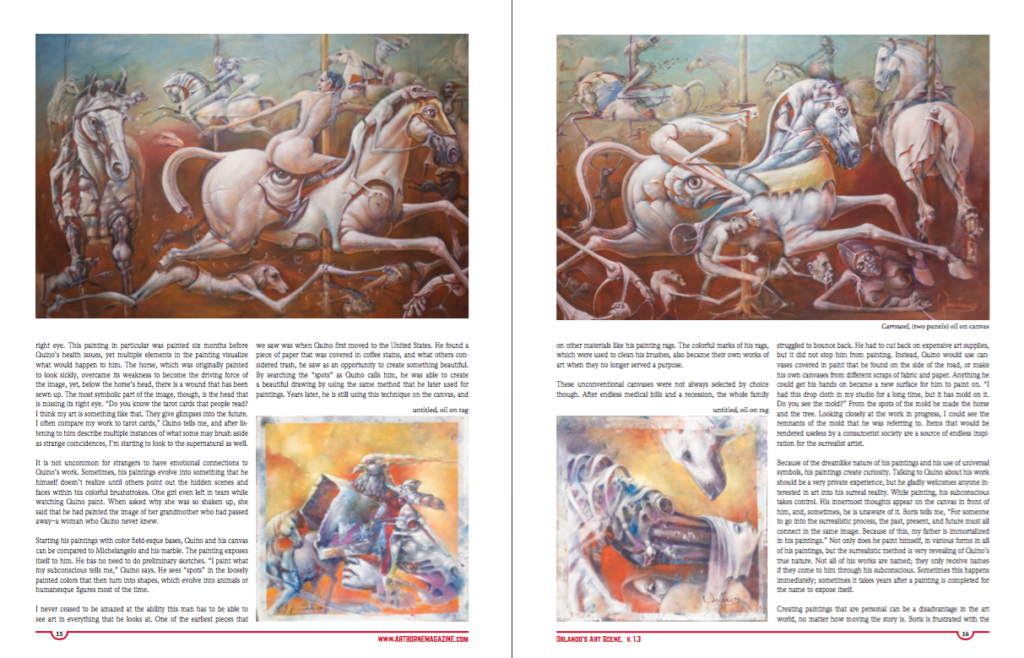

The aptly named documentary “Before the Lights Go Out” is documenting Quino’s process and his work before he loses his ability to see. While looking at one painting in particular, The Mystery of the Light, Boris points out to us that most of his father’s figures are missing their right eye. This painting in particular was painted six months before Quino’s health issues, yet multiple elements in the painting visualize what would happen to him. The horse, which was originally painted to look sickly, overcame its weakness to become the driving force of the image, yet, below the horse’s head, there is a wound that has been sewn up. The most symbolic part of the image, though, is the head that is missing its right eye. “Do you know the tarot cards that people read? I think my art is something like that. They give glimpses into the future. I often compare my work to tarot cards,” Quino tells me, and after listening to him describe multiple instances of what some may brush aside as strange coincidences, I’m starting to look to the supernatural as well.

It is not uncommon for strangers to have emotional connections to Quino’s work. Sometimes, his paintings evolve into something that he himself doesn’t realize until others point out the hidden scenes and faces within his colorful brushstrokes. One girl even left in tears while watching Quino paint. When asked why she was so shaken up, she said that he had painted the image of her grandmother who had passed away–a woman who Quino never knew.

Starting his paintings with color field-esque bases, Quino and his canvas can be compared to Michelangelo and his marble. The painting exposes itself to him. He has no need to do preliminary sketches. “I paint what my subconscious tells me,” Quino says. He sees “spots” in the loosely painted colors that then turn into shapes, which evolve into animals or humanesque figures most of the time.

I never ceased to be amazed at the ability this man has to be able to see art in everything that he looks at. One of the earliest pieces that we saw was when Quino first moved to the United States. He found a piece of paper that was covered in coffee stains, and what others considered trash, he saw as an opportunity to create something beautiful. By searching the “spots” as Quino calls him, he was able to create a beautiful drawing by using the same method that he later used for paintings. Years later, he is still using this technique on the canvas, and on other materials like his painting rags. The colorful marks of his rags, which were used to clean his brushes, also became their own works of art when they no longer served a purpose.

These unconventional canvases were not always selected by choice though. After endless medical bills and a recession, the whole family struggled to bounce back. He had to cut back on expensive art supplies, but it did not stop him from painting. Instead, Quino would use canvases covered in paint that he found on the side of the road, or make his own canvases from different scraps of fabric and paper. Anything he could get his hands on became a new surface for him to paint on. “I had this drop cloth in my studio for a long time, but it has mold on it. Do you see the mold?” From the spots of the mold he made the horse and the tree. Looking closely at the work in progress, I could see the remnants of the mold that he was referring to. Items that would be rendered useless by a consumerist society are a source of endless inspiration for the surrealist artist.

Because of the dreamlike nature of his paintings and his use of universal symbols, his paintings create curiosity. Talking to Quino about his work should be a very private experience, but he gladly welcomes anyone interested in art into his surreal reality. While painting, his subconscious takes control. His innermost thoughts appear on the canvas in front of him, and, sometimes, he is unaware of it. Boris tells me, “For someone to go into the surrealistic process, the past, present, and future must all connect in the same image. Because of this, my father is immortalized in his paintings.” Not only does he paint himself, in various forms in all of his paintings, but the surrealistic method is very revealing of Quino’s true nature. Not all of his works are named; they only receive names if they come to him through his subconscious. Sometimes this happens immediately; sometimes it takes years after a painting is completed for the name to expose itself.

Creating paintings that are personal can be a disadvantage in the art world, no matter how moving the story is. Boris is frustrated with the process of showing art, “We don’t do art shows for the restrictions and for the respect that they don’t seem to understand the point of it.” Quino is not necessarily looking to sell his work, he simply wants to share his talents and stories with others in the hope that they can walk away from his work intrigued. With such stylized paintings, he has faced a lot of rejection as an artist. Boris notes how “people do not understand how his paintings come alive. ‘This is not sellable art. It needs to match furniture. Can you change the color? The colors are too sad or too aggressive.’ ”. Time and time again, they hear the same message. Even though Quino is not looking to sell his art, the galleries are, so they are only interested in promoting art that sells.

Quino’s goal as an artist is to inspire others. He gets joy out of creating anything, and sharing his creativity. “I was making many things when I felt good. Painting, gardening, cooking–I like to cook–I like to make everything. But when I was sick, I felt very bad. Painting helped me a lot.” Painting helped him get through chemo, and even though his vision is almost gone, he still continues to paint beautiful scenes. I asked Quino if he would still paint once he is completely blind, but he seemed more interested in the idea of creating sculptures again.

Victor will be showing a solo exhibit, Secrets of the Unconscious Mind, at Osceola Arts September 13 through October 27, 2016

You can see more at: BorisQ.wix.com/QuinoArtStudio

Thank you Artborne for showcasing Quino’s work. We are so excited to be exhibiting his work at Osceola Arts during Hispanic Heritage Month. Keep up the great work. Looking forward to your next issue!!!

excellent article, I feel like you captured the artist struggle and also his humble personality. Thank you for giving him a spot in a the world of art. He surely deserves it.

Thank you for this insightful tribute to Victor and his artwork. He is a truly wonderful man as well as a fantastic artist. I have been experiencing his talent for a few years now and I am always impressed.

Very special article about Quino’s work.I enjoyed his art and talent.I really like his style.

I can’t wait to be there at Osceola Arts.

Good luck!!!

I am very happy for Don Victor, he is a great human being and an extraordinary artist. Thank Artborne to recognize the great talent and contribution to the art that has made Victor Quino, he deserves it. He is a very admirable person, who has managed to turn their sacrifices and struggle, in masterpieces of art. I congratulate you for the excellent article,

BRAVO!

I was so fortunate to see and feel his art. Muchas gracias Don Victor.

I so love his work. I would love to purchase a print. Can anyone give me any information regarding this. When and where is his next exhibit?