It’s 2015. I arrive early to a Glenn Grishkoff lecture at the University of Central Florida. Too early it seems. The room is all but empty, save for Glenn in the front preparing his brushes for the coming lecture, and Jordan. I find my way to a seat, ignoring the empty ones, and place my bottom on the chair inches away from Jordan Senarens. I introduce myself. She doesn’t seem interested in making conversation, but she humors me nonetheless. I find she has a studio space in the room adjacent to the one we are in. I calmly continue with the conversation, even after I discover she’s responsible for the pieces I’ll soon come to know as the Diffracting Series. I fall in love — not with her, mind you — but with her work. It has an air of simple elegance, and com- plexities I can’t comprehend. She is, after all, a recent transfer from the biology department.

Over the next several months I run into Jordan on campus, as I’m so prone to do anytime I want someone to be my friend (a ceaseless campaign of ‘random encounters’). She relents, and allows an interview. I believe she’s finally comfortable, so I confess I’ve been slaughtering the pronunciation of her last name.

Open curtains, enter scene.

Jonathan Yubi: Senarens, where’s that name from?

Jordan Senarens: I think it’s Cuban.

Cuban? You have Cuban descendants in your family?

Yeah.

Mother’s side, or father’s side?

Father’s.

Speaking of family, tell us a little bit about yourself.

Well, I’m from Fort Lauderdale. My family…. I have a very small family. And my father moved to India, he was a landscape architect. I think that’s how I get a lot of my overall clarity of my landscapes. I make each piece of foliage, as an icon. So everything is perfect. And that’s how I remember all of his drawings when he was designing landscape. So I think I’m more influenced by him than I thought I was.

That’s cool, I didn’t know your dad was a landscape architect.

Yeah, so I did all of these drawings of location with marker, but they were real places. This one is imagined. The other one I did isn’t imagined, it’s from photographs.

So your father, obviously a big influence on your life. How about your mother. Was she involved in any sort of art?

She’s crafty. But she always supported my decision to be an artist. I got a lot of pushback from her brother. He was like, “I would never let my daughter be an art major.” She said, “If she thinks she can do it, she’ll do it.” So I always had a lot of support from everyone in my family.

That’s interesting though. I’ve always been very interested in your decision for a career change. Can you tell us a little about that? About what you were doing before, and why you decided to move into this.

I think I decided I wanted to be an art major when I was in middle school. So I was always set on that and then before I really found what I wanted to do in art, I was panicked all the time thinking I wasn’t gonna make it work. And I think my biggest panic was my sophomore year here. Because I got my associates degree in high school, I went straight into my core classes here at UCF. I really missed math and I wanted the ease and the — what word am I looking for? The… knowing you’re going to be successful. The… what’s the word I’m looking for?

I’m not sure.

I just wanted to know that it was going to be successful. You know? If I had switched, well I switched into wildlife biology, but then that seemed unrealistic with what I wanted to do with my life. So I devoted myself to this and eventually I did the painting Detracting Light and that really started everything. And it kinda got me on this… got this ball rolling.

So physics? And biological sciences. Is that what you said?

Wildlife Biology

Wildlife biology. That’s obviously… you’re obviously passionate about that. What made you decide that art was more… was more of your career path then the sciences?

I think I just felt like I had to do it. It was something that I knew I was good at, and if I really knew that I could do it, it would work out. And I… like I wouldn’t be happy doing anything else. So I just decided to incorporate the different subjects I like into my art.

You recently had your work at the Henao Contemporary Center, was that your first show outside of UCF?

Yes. I’ve had shows in UCF and related to UCF. But that was my first. I’m going to get an MFA eventually. Probably take one or two years off. I’m going to get an MFA and I’m thinking about an MBA because I want to start a teaching studio one day.

So what are your goals the next couple of years since you’re going to take a break?

Just keep showing, and try to live off of my art, and build a really good body of work to apply to an MFA program. Because I really want to get paid to get my masters… or at least not have to pay.

There’s some good programs in Illinois. Are you trying to stay in Florida for your MFA?

I kinda want to go to RISD. Which I probably won’t get a full ride to RISD.

We can hope, huh?

Yeah, but I’ll probably get a scholarship to go there. And I think I have a New England influence on my aesthetic.

In what way?

I think my subject matter or my houses are very Florida, but I think aesthetically I belong in the Northeast. Instead of being around all this Miami art, which I appreciate, that’s just not what I do.

Of course. So how does that make you feel? Knowing you’re new in the game?

I think everyone has to go through that. And I just have to prove it – to any potential investors – that I’m going to stick with it. I devoted my whole life to this, so hopefully, other people will realize that. You only need a couple people to support you before it starts working out.

How do you feel about the culture and arts in Orlando?

I think it needs to be more.

It’s such a vague word. Like “How”?

A lot of people in Orlando are just not educated in art. And it’s too new in the area, but that’s not to say it’s not going to change. It’s just developing. It’s not well estab- lished like New York or Southern California.

It’s a lofty comparison whenever you compare to New York.

Or even Atlanta. Even Santa Fe.

Yeah, I‘ve heard Santa Fe is great. There’s such a big market there.

I was just there in December.

Really, how was it?

I really enjoyed it. There’s a lot of very… institutional art… decorative? I think that’s the right word.

I can see that. I see a lot of older artists migrate to Santa Fe.

There’s also a lot of Native American art. That’s a big influ- ence. Which isn’t decorative, I’m not saying that.

No, of course. I understand what you’re saying. That be- ing said, I mentioned Philadelphia. They’re really big on their mural scene, and all these bigger cities they have a kind of presence, an essence. What they’re known for. If you could – I don’t know if you could – how would you describe Orlando? What’s our community, our arts?

I don’t think I’ve been in it long enough to know, to give it a word, to sum it up. I would say it’s not as conceptual.

How would you describe your work, in that context?

It’s accessible but very conceptual. My houses I’m work- ing on. Aesthetically, they’re very easy to reach. But they’re thought provoking.

What’s the meaning behind the houses? Why do you create these fractured shapes?

I like overlapping time, and to do that, you have to over- lap space. Because that’s how you view a moment in time.

Every piece I do has its own formula I develop, they each have their own rule. For example, in Diffracting Light, there were no black triangles. That was the rule. And I don’t make changes, ? times out of ??. I’ll make a mark, and then make it work. Once it’s there, that’s where it lives. It gives it a permanence.

*Rob Goldman joins the conversation.*

Jonathan: Here, take a seat man. I’ve been sitting all day.

*Rob sits and chats with Jordan. I walk off. When I return, they’re talking about influences.

Rob: Earlier I asked her, “What do you want to be asked,” and she said, “My influences, of course.” So I asked her and she said, “Diebenkorn.”

His Ocean Park Series, they were a big influence to my House Series.

Rob: And you’re primarily a painter, right? What’s your role in art?

Art doesn’t need to be about art. Or politics. I paint what I’m interested in, which is science. But it’s accessible to the public. Looking at it, you can see the person that made it had an understanding of something.

Rob: And you want people to read it better? Is that a goal of yours?

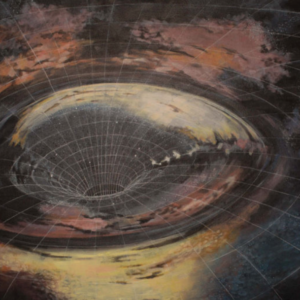

I think bringing my interests to an audience that doesn’t necessarily know a lot about it— generally. And also bringing science people to the arts. My work started really illustrative, like my black hole nebula. And as I progressed, it became solely about diffracting space or time. And about overlapping time. It’s the same position in space, but seen in the present, and either the future or the past, depending on how you see the landscape. It’s about making flat planes appear to be optical cubes.

Rob: Is science helping identify you as an artist?

Yes, I would say I’ve been influenced by Picasso and his cubism. And he was in- fluenced by Einstein’s Theory of Relativity.

Jonathan: What’s your dream project?

I want a solo show with a neighborhood of my hous- es. Each of them as large ?-foot paintings.

Rob: What was the best piece of advice you’ve received?

Everything that’s coming to my mind is really cliché. I was really inspired by Carla Poindexter because all of her work is very scientific also, but more imagined. She makes little flying machines. I haven’t gotten a lot of negative feed- back. I like to say I’m intrinsically motivated. I was always terrified to do bad in school… and I’m not old enough to be wise.

There have been some unsuccessful pieces, like…

*Jordan goes to the back of her studio to retrieve a painting she deemed unsatisfactory.*

Rob: How much you want for it?

Jonathan: I have three dollars in my pocket right now!

Rob: I got $15!

Jonathan: Dammit… Hey, you know who your work makes me think of? Hold on I can’t pull it up, I’m using my phone to re- cord. Maybe I’ll just end the recording.