The unlit tip of Joe’s Pall Mall cigarette hung onto his lower lip. I kept waiting for it to fall. It didn’t. It never fell. The ember moved up and down slowly as he matter-of-factly stated that my brother was going to be a left-handed DiMaggio someday. The three of us were on our way to meet track and field legend Jesse Owens at the Sunrise Inn, across from the beach. In a month, this area would be what it was most famous for at that time: prime spring break territory. This is where the film Where the Boys Are accelerated a spring break tradition, and spawned a bunch of other films that seemed to get progressively more hedonistic and shallow. It was also where the New York Yankees played during spring training.

My parents told me stories of seeing the infamous playboy “Murph the Surf” in Lauderdale bars in the late ’50s and early ’60s. He was known for buying entire crowded bars a round. His charm blurred suspicion that a young surf bum had plenty of money. Later, he was arrested in the biggest jewel heist in American history. His charm diminished when he was busted for killing an ex-girlfriend. In the mid-‘80s, he was released early from prison after he found God. My father said anyone with any sense would claim to have found God in hopes of an early release.

My brother and I were still in Little League. “DiMaggio was the first real five-tool player,” Joe said. “He could hit, hit with power, field, run, and throw.” Joe discreetly sipped his Schlitz, placing the bottle between his legs as he spoke. I had to remember not to rest my hands on the seats of his Pontiac Tempest, because the seats were sticky from spilt beer. The 1967 Tempest was only three years old, but had not aged well. There were stained racing forms on the seat and a couple of empty beer bottles rolling around, clanging every few minutes. Rust was making its way onto the unwashed body. The windows were cracked open, but not enough to ventilate us from the smell of stale beer and smoke. The interior looked like the photos of post-communist Eastern Europe: the unproductive factory where the Peace Corps intervenes, or the smoke-filled car from the dream sequence at the beginning of Fellini’s 8 ½. Now, I imagine a larger-than-life balloon looking like Joe, tethered and floating above the car, like at the end of the dream.

“Your arm might be stronger in the end,” Joe continued. He took a drag as he assessed my ten-year-old brother’s baseball abilities and looked him in the eye. “You could be another Clemente as far as that goes.”

“Did you know DiMaggio?” I asked Joe.

“I met him a few times. He may not remember me. I was covering baseball for the Cleveland Plain Dealer in the ’30s. I met his brother Dom a few times—hell of a player, too. Dom was a better fielder, and faster. You know Joe D. injured his knee getting out of a cab when he was in the minors? He was supposed to have had blazing speed prior to that.”

As he spoke, Joe maneuvered the steering wheel as if we were on a ride at a fair. We slid in and out of lanes, narrowly missing other cars and occasionally brushing curbs. Rain drizzled down from a sunny sky. The windows fogged up as the Tempest floated through the mist.

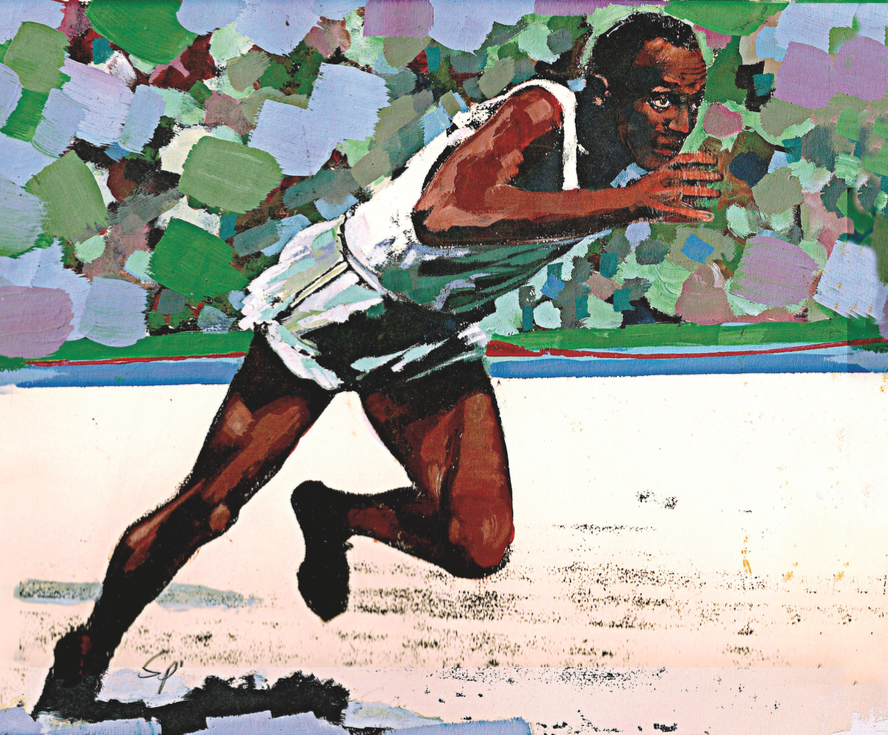

Jesse Owens, painting by Spencer Petit

“Do you think he was as fast as Jesse Owens?” I asked.

“Hell no. Jesse was the fastest human of all time. His records have been broken, but the equipment was crap then. Track shoes were much heavier. Starting blocks didn’t exist. Most of the tracks were gravel, and were much slower. With today’s training, Jesse would have blown anybody away, including Bob Hayes [the 100-yard dash record-holder at the time].”

We continued to talk about Jesse Owens as we headed down the palm tree-lined Sunrise Boulevard towards the hotel on the corner of Sunrise and A1A, Ft. Lauderdale. After we passed Highway 1, I saw the Wolfie’s neon sign on the left. I wished we could eat lunch there. It was one of my favorite places to eat. The Jewish deli is now long gone. Ft. Lauderdale seemed to be on a tear to erase the past.

We drove over the drawbridge that crosses the Intracoastal Waterway after waiting for the bridge to come back up. I watched the large sailboats cross under, and I looked across the water towards Hugh Taylor Birch State Park. My brother and I loved riding the 3-mile-long tourist railroad that took us around the small park. The park was touted as a stop on the route for the almost mythical “barefoot mailmen.” The carriers travelled up and down the coast of south Florida delivering mail on foot.

Joe had arranged for us all to meet with Jesse Owens for lunch at the hotel restaurant. My father was also supposed to meet us there. He didn’t seem too excited about the lunch date. He never encouraged my brother’s and my interest in sports. Joe had gone to Ohio State in the early ’30s, the same time as Jesse. I had been reading a lot about Jesse Owens and how Hitler wouldn’t acknowledge him when he won four gold medals in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. Joe told my brother and me that he was good friends with our hero in college. My father seemed doubtful; he was usually a skeptic. My father was staying at the Sunrise Inn, too. He was there on business.

Joe was my step-grandfather, married to my father’s mother, Edee. Edee and Joe seemed more like drinking buddies than a couple. Joe had apparently drank his way out of several good jobs, including some foreign correspondent positions. Now, he worked as a sports reporter for the local paper in Ft. Lauderdale. The job may have been closer to entry-level, but had plenty of perks for sports fans like my brother and me. We got a tour of the Yankees’ locker room when Mickey Mantle was there. He had retired a year prior, just before the 1969 season, but he was still active with the organization.

It was common knowledge that my father didn’t take Joe very seriously. He often referred to him as a fuck-up.

We pulled up in front of the hotel. My father was standing out front. He looked dapper, wearing a dark suit and Ray Bans. He was uncharacteristically punctual. As the car approached, Dad made his way towards the driver’s side window. Joe rolled the window all the way down. He asked my father if he would mind him leaving to pick up his dry cleaning around the corner, since he was a little early. My father agreed. We got out of the car as Joe drove away. My father seemed to be playing down our lunch meeting. I was annoyed that he wasn’t taking it seriously. We were getting ready to have lunch with one of the greatest athletes of all time, and my father acted as if it was kid’s stuff.

Jesse Owens walked out a few minutes later dressed in a crisp, gray suit, smoking a cigarette. He was in his mid-50s. He looked dapper and lean. He put his cigarette out in an ashtray in front of the lobby. I was surprised and disappointed to see him smoking. I later read that he was a chain smoker. He died in 1980 of lung cancer.

My father walked over to my brother and me. He asked if he could have a minute to talk to Mr. Owens. We waited. They stepped far enough away that we couldn’t hear their conversation. It seemed like they were talking for a while, but in reality it was probably only a few minutes. Afterward, my father walked toward us and said, “Stop by my room when you’re finished.” Jesse introduced himself to us. He was very polite.

“Dad, aren’t you coming to lunch with us? What about Joe?” I asked.

“I’ve got some work to do. Don’t worry about Joe. He’s not coming back.” He sounded a little impatient with my questioning.

“What? What do you mean he’s not coming back?”

“You’ll be okay.”

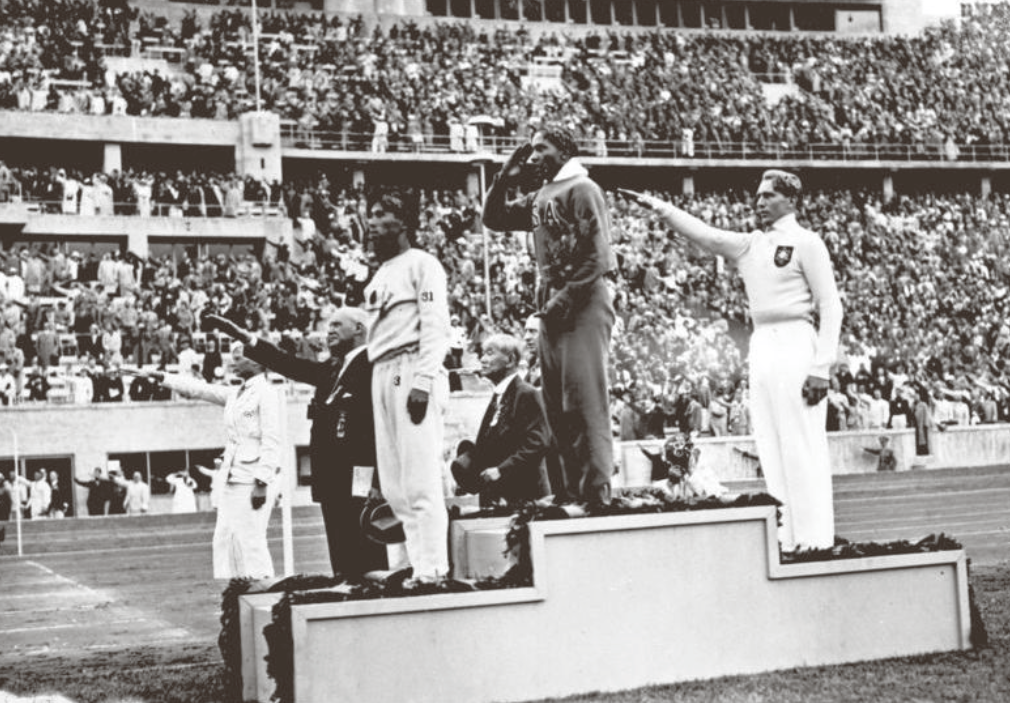

Jesse Owens on the podium after winning the long jump at the 1936 Summer Olympics. L-R, Naoto Tajima, Owens, Lutz Long.

We walked to the restaurant with Jesse Owens. I was elated, but confused by Joe’s disappearance and my father’s nonchalance about it—although, my father was mysterious about lots of things. We knew he made good money, but we didn’t know what he did for a living. He would say something like, “I’m a businessman.” A couple of years later, he was busted for mortgage fraud—that’s how we found out his occupation. He did a short stint in a minimum security prison.

At lunch I ordered my favorite: a club sandwich with chips, pickles, and a Coke. I had memorized all of Jesse’s times in high school, college, and the Olympics. When I asked him about Joe, he would say something general like, “He was a good guy.” He didn’t offer up anything on Joe. We mostly talked about track, especially Jesse’s career. I asked him about Hitler ignoring him after he won four gold medals.

“He didn’t seem interested in greeting me. Hitler was using the Berlin Olympics as a showcase for Germany. I imagine my winning four gold medals put a damper on that,” Owens recounted.

“Do you think you could break Bob Hayes’ record of 9.1 in the 100-yard dash if you had the tracks, starting blocks, and shoes they have today?” I asked.

“I see that you’ve thought a lot about this. You ask better questions than a lot of sports writers. It’s impossible to say what I could do under current conditions if I were in my 20s. I think I could break the record, but there is no real way of knowing. Pat, do you run track? You definitely know about it.”

“I’m one of the fastest kids in my grade, but I guess that’s not the same as being the fastest in the world.”

After lunch, we went by his room. We waited in the doorway as he grabbed two black-and-white photos of himself wearing a suit very similar to the one he was wearing that day. He autographed both—one for me, one for my brother. My brother had been a lot quieter than I had been. He was still a little shy. After saying our goodbyes and thanking him, we went to my father’s room. We were so excited to show him the autographed photos. He barely reacted.

He drove us back to our grandmother’s house. She lived about ten miles west of the beach, in Plantation. My brother, mother, and I had been staying with her and Joe since my parents had split a few months earlier, a couple of months before my twelfth birthday. My brother and I ended up encouraging my mother to leave my father. We wanted peace, and my father seemed unsatisfied with anything any of us did. We were tired of the arguments, and my mother was visibly unhappy, and I think she held back a lot in front of us.

That afternoon, my father explained to us that Joe left because he was embarrassed. When we asked why, he said Joe was trying to impress us by saying he was friends with a hero of ours. He asked us if Jesse Owens volunteered any information about Joe. When we asked what he meant by that, he said, “Did he just say things like ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ or ‘I really liked him’—comments that were vague?” Dad said that Joe had lied. He didn’t know Jesse Owens. I finally agreed that might have been the case. But how did Joe get the meeting in the first place?

Dad said that when Joe called to set up the lunch meeting, he said something like, “Hey, it’s Joe from college,” and Jesse probably thought he’d met so many people in his life that he might be forgetting that guy Joe that he hung out with briefly. In 1970, it was easy to call a hotel switchboard and get through to someone famous. We fell silent. At that point, our father finally showed some compassion. “He lied,” Dad continued, “because he really loves you guys, and he’s a fuck-up, and he thought he could shine, and in a way, he did.”

“It was nice of Jesse Owens to meet us for lunch,” my brother stated quietly.

“Yes, that was very impressive, in twisted way. An amazing gesture, really. He didn’t have to do that. He didn’t know any of us before today. That’s why I went over to talk to him before lunch. I offered to get him off the hook. He said no. I told him to charge it to my room. He said no, he would buy you guys lunch. He knew the whole thing was important to you kids.”

When we pulled into the driveway, we all got out. We walked through the carport and back to the pool area in the backyard. Joe, Edee, and my mom were sitting poolside at the table they ate many meals at. They were all drinking beers. Joe and Edee were both smoking. Joe just looked down at the table, and mumbled something about getting tied up at the dry cleaners. My mother quickly changed the subject and asked us all if we wanted something to drink. My father said, “No thanks.” We walked back out to the driveway to say goodbye to him. Dad turned to us right before he got the car and said, “Hey, I think it would be a good idea if you didn’t bring up Jesse Owens around Joe. Don’t ask him where he went today. Okay?” My brother and I both said okay. “Hey, I love you guys.” Then, he hugged both of us and drove away.

Very nice piece Pat! You are a gifted writer. I’m still smelling the car and beer/cig combo. They were a pair weren’t they? Thanks for sharing.

L