Aaron and Sheila had moved south, so far south that they went past the south until their vista was the Atlantic, from atop the flat peninsula, jutting from the edge of America. Their fortunes were supposed to change in Jacksonville Beach, where her parents had relocated for the sort of retirement that, for puritanical elderly folks, counted as decadence. Shuffleboard. The landscape looked like it had licked itself into existence off of a color brochure. Pastel architecture pushing itself into an impossibly blue sky. The ocean sighed. It was beautiful, but alien, somehow. The sand didn’t feel natural or pleasant to Sheila’s feet. It felt dirty. The air was humid, making her lungs tire out with breathing, the sun this spigot from outer space. She glazed herself with coconut oil at the beach, and her skin began to tan and freckle. Without cold winters, Aaron could find work all the year round painting houses. They could become middle class. Sheila loved him, almost as much as when they were first married. He had changed. For a while, he had changed.

They made friends with another couple, Tom and Francine, who they would go square-dancing with. And friends from Boston would come down every few months to visit. But in between times, Sheila started to get a case of nerves. She was young, lithe, and beautiful, just a few miles from the beach. But she felt not right, somehow. Even though her parents lived three blocks away in a duplex, Sheila didn’t like to spend too much time with them. Their company made her feel like a married spinster. The game shows and the soap operas on the floor console Magnavox bored her, until General Hospital came on late in the afternoon. She would thaw out the dinner’s meat before the show, and start cooking when the end credits rolled. Or she might have cabbage stew stewing in the crock-pot, puffing its pungency throughout the house while she watched her story.

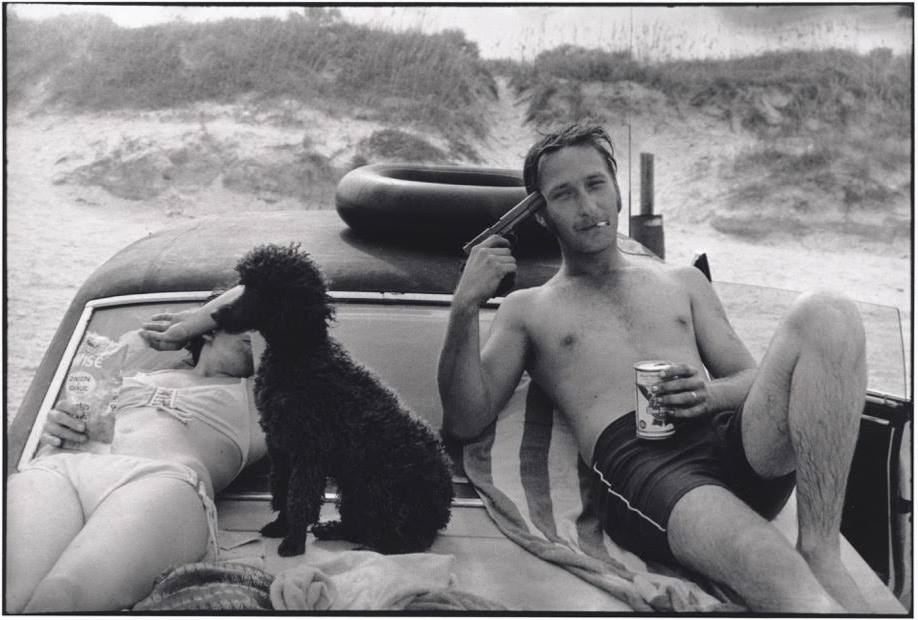

Photo by Christopher Bolton

Sometimes Aaron would come home late, after having stopped for drinks with the painting contractor he worked for. He was out of the door before dawn, and worked until five P.M., six days a week. She wanted him to have a drink, if he wanted a drink, but she didn’t want him to have five drinks. He was a good man, if. She couldn’t accept Boston again. She tried to keep dinner edible if he arrived at seven, or eight. At nine, she would throw everything out, and watch the news while drinking what may be her twelfth can of Tab, and smoking her cigarette, feeling its weight in her lungs.

They were trying to have a baby, although Aaron always worried about money.

Sheila got nervous being in the house alone. She bought a dog, a black poodle named Sugar, to keep her company. Burglars are afraid of dogs, even poodles. Sugar would watch General Hospital with Sheila, that long snout, both dignified and absurd, pointed like the barrel of a gun at the screen. Aaron never liked the dog, eventually confessed that a poodle made him feel queer every time he walked her. Sheila pointed out that Sugar was a black poodle, to which Aaron retorted that he would rather own a pink German Shepherd. Sheila giggled and kissed Aaron. Every two weeks she took Sugar to the groomer, to keep her fur sculpted in its French, cartoony way. When the mailman arrived, Sugar would go manic.

The dog was like General Hospital. The dog was not a baby.

In Boston, there had been a miscarriage.

During tourist season, during the week, Sheila didn’t like taking the Volkswagen out to the beach by herself, the way some of the men would look at her. Like she was a medium-rare slab of prime rib. Sometimes Sheila could not bear it. Without the tourists, mostly old people and families inhabited the shoreline. She could sit in a deck chair and read her magazines, sleep while cocoanut oil quickened her flesh. On Sundays, she coaxed Aaron to go to the ocean.

One Sunday, during the season when tourists swelled over the beach, Aaron and Sheila drove out in the Charger to the water. Overhead, the overtures of dusk burned in swirls of bronzes and blues. Sugar craned her skull out of the passenger window. They parked at the public lot, surrounded by the gnarled paddles of sea grape. Once on the sand, the couple could barely walk between flesh, and Sugar misbehaved like a nuisance, psychotically insistent upon sniffing everything. The seagulls squalled overhead. Aaron squinted into the blinding sky, afraid a glop of white shit might squeeze out of the humidity. Sheila could feel his tension in her own bones. “Let’s go back home,” she whispered, as he yanked at Sugar’s leash.

“No,” said Aaron. “The crowd’ll scatter in a bit. Let’s just wait.”

“We could go home and come back.”

“Wait here,” Aaron said. He walked past the parking lot, across the street, and into a liquor store. Sheila sighed, watching its tinted door swing closed. She crammed towels back into the front seat, and hopped up onto the Charger’s hood. Sugar put her paws on the glossy white fiberglass, and lifted her snout the Sheila’s face. Sheila unsnapped Sugar’s leash. The dog leaped onto the hood, and sat upon her hind legs, looking like a French sphinx. Sheila scratched the poof of black wool atop Sugar’s head. Sheila looked through the shade of her sunglasses at the distant ocean sighing.

Aaron arrived with a six-pack of Pabst Blue Ribbon, which felt more patriotic than the fourth of July. He yanked a cold cylinder from the plastic holder, and gave it to his wife. The beer felt beautifully cold in her hand. It could not possibly taste as beautiful as it felt in her hand. Aaron got back in the car for a moment, but didn’t start it up. She could feel the vibration when he opened the glove compartment for something. Then Aaron came out, sat on the other half of the white hood, and popped open his own Pabst. I am beautiful, thought Sheila, I am happy, as the beer’s temperature rose to meet that of her body. She looked out to ocean, with Sugar keeping watch to the south, with her husband sitting near her. We are in this together, she thought. Everything is going to be okay.

______________________________________________________________________________

This ekphrastic story was written for Florida Overtures, Undertones, and Subplots, a collaborative art show and reading sponsored by The Gallery at Avalon Island and Burrow Press.

You can see more at: TheDrunkenOdyssey.com