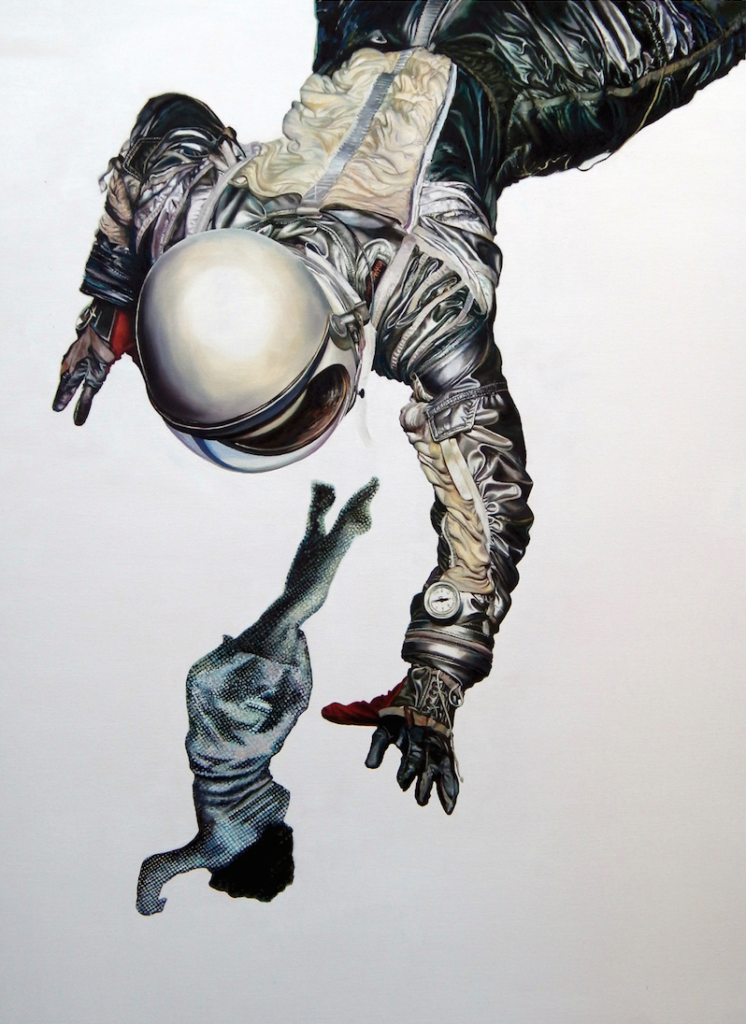

Walking into Kyle’s indoor studio space, we were faced with a large painting of a photorealistic astronaut falling with his hand extended. Reaching up is a comic strip style woman who appears to be falling upward. The two figures within the painting are portrayed in completely different styles, yet they exist together in the light void within the canvas. Kyle has an amazing talent for combining different styles of painting all within one beautiful image that appears to be some kind of larger-than-life collage. He also explores the themes of devastation and relationships through sculpture and shadow boxes, but we begin our interview talking about the anonymous man falling through the sky, his face shielded by the iconic glare of an astronaut’s helmet.

On Strange Footing, oil on canvas

Kyle: It’s not about space. It’s not about NASA. It’s about relationships. Guys—in our minds—we’re always in uniforms. We’re superheroes. We’re living in a sci-fi world most of the time, which can be alien to the women that we like. It makes us almost from different worlds. How do we reach each other; how do we communicate? I started pushing relationships as a focus when I discovered, about seven or eight years ago, how important relationships are to everything.

Jenn Allen: And not necessarily romantic relationships, just relationships in general?

Yes. Sometimes it can be a person against nature, or against their community. It can be a body of people. My large works in progress are about social statements and our culture, where this is about just one guy and his obsession, or disappointment.

I like that this piece is open-ended though. I can see how people would consider it optimistic. Even though they are falling, he is very close to reaching her.

I’m glad that you see optimism in my work. I was called Pollyannaish in grad school, but no one has called me that in a long time. This is not as dark as what I have been painting. I’m getting sick of dark; I’m getting lighter. I went through my dark phase post-Katrina, post-9/11. I made Katrina work and I’ve made 9/11 pieces. Those events really influenced me and they continued to be a part of my work as external destruction going on around us. I had heart failure about seven years ago and I was thinking, “If I survive this,”—I was in bad shape—“I hope I get to paint again.” When I did, I wasn’t thinking what I would paint, but I went right back to disaster paintings. I wanted to pick up my life and continue, but it wasn’t about external damage anymore. I stayed with damage, but it became internal. If you live long enough, you go through a disaster. It may be a relationship, money, life, jobs, where you live, what you thought was home. Sooner or later, you lose that and it’s a catastrophe, but you survive it. We’re all survivors.

More Choices Than Time, acrylic and collage on panel

That’s very powerful.

Now I’m moving beyond that because I love the damage, but I’m sick of the damage. A lot of what I make, they can’t sell in Miami. It’s too dark, too edgy. Virginia Miller represents me. They have more accessible work.

Do you collect magazines and comic books since you use them for your sketches?

Yes, but I’m not responding to the narrative in the comic books—I don’t even read what they’re saying. For example, I love people falling. If I find a good falling picture, it will go in a stack. I have stacks of boxes. The pieces that are collages are mock-ups. If they work, I sell them and make bigger pieces.

Untitled #II, (from the Floating, Flying, and Falling series), oil on canvas

So you start off with the collage, and then you paint them?

The collage informs the painting. It’s always changing. Scale changes everything. But that’s okay, because I want to make something new every time. I like painting and collaging in a way that you can’t tell where the collage begins and ends, or where the painting begins and ends.

I love that you have to get up close to see that it’s actually a painting and not a blown-up magazine.

When I build these collages, I try not to be too anatomically correct or specific with it—I just toss them. And when it works I say, “Okay I’m going with that.” I don’t have any meaning originally embedded in it, but once I start painting it starts taking on meaning.

Everest Green + Silver, mixed media

I like how you use different painting techniques. Some of it is really tight, some of it is loose, the text is really clean, and then you have impressionistic debris. So you go with what feels right at the time and you just let it evolve?

If I can make it loose so I don’t recognize it, then I like it. I don’t want gravity to work on it. I like looking at people and wondering, “Are you seeing somebody on their way up, or their way down?” We all make those assessments. I’m trying to describe our culture, what our culture feels like. Gravity isn’t working. There is just so much going on; eye candy everywhere. As a culture, we like devastation and catastrophes.

Katrina, mixed media

You also make sculptures. Are all of your constructions made of toys?

Yes, and junk that I pick up like urban seashells. I like to let something real and organic in the piece like a piece of fossilized wood or a geode; something mineral with the plastic. I’m trying to push the plastic world with the real world. We are surrounded by it. You can look at things and wonder if they are natural or man-made, and it happens all the time. Then I started embedding transformer constructions in them because I see technology as tied to our devastation. I made about eight of these pieces. I enjoy making work that doesn’t fit a category—I always have.

Rauschenburg Inspired Transformer, mixed media