To say that humans in the twenty-first century live in a disposable society is a horrifying understatement. “Disposable” is a term no longer relegated to diapers and coffee cups. In 2017, it is more often cheaper to replace a broken object than to attempt to repair it. The adage “they don’t make things like they used to” applies to nearly everything used by humans in a typical first-world day—cars, appliances, clothing, and technology.

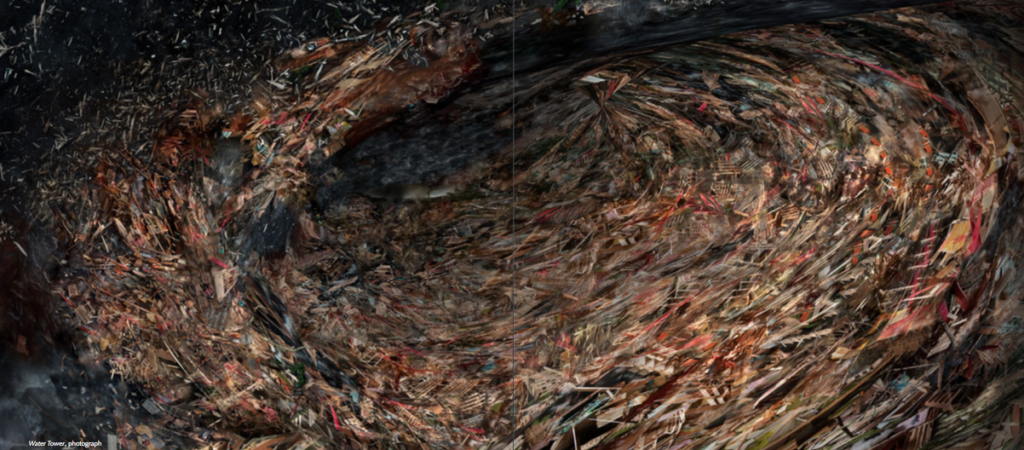

Water Tower, photograph

To think of technology as disposable may seem ironic, especially when considering the amount of money spent on cell phones, computers, laptops, tablets, and other tools of communication. But technology is that dubious industry that is both indispensable and easily replaced, blending reason and madness. It is a necessary evil that requires consumers to repeatedly upgrade to the newest, the fastest, and the most powerful version of itself. It feeds the need for a constant flow of information, so much so that when it breaks, life itself seems to stop. As the flow of information goes, so goes one’s livelihood, and technology is both the needle and the drug.

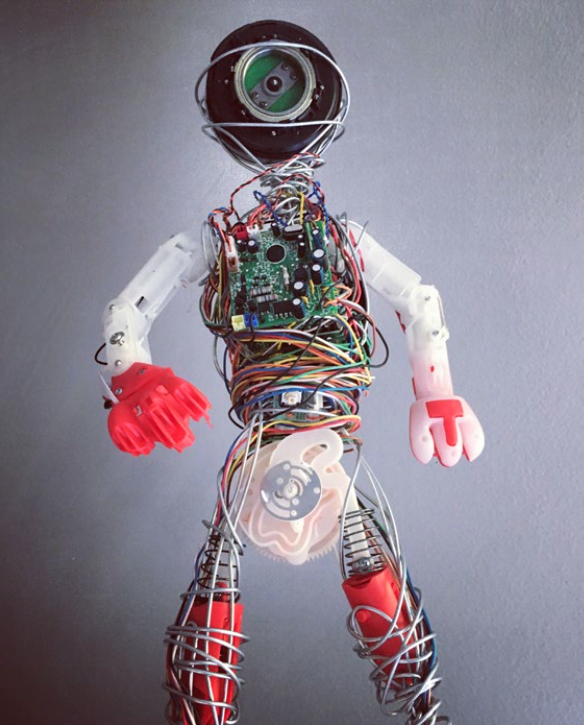

Andrew, mixed media

Recognizing the wastefulness of discarded, outdated technology, Forrest MacDonald is an artist literally making old things new again. His 2016 sculpture series, Wired Up, includes seven characters created by “using fragments taken from deconstructing broken obsolete technologies” to create life where it was lost. These new sculptures are a stark contrast to his previous work, and one cannot fully appreciate their power without seeing them in relation to his past projects, namely his 2012 photography series, Recipes for Disaster. On the surface, the two creative endeavors may seem at odds: one is photography of grim scenes of ruin, the other is blissfully sculptural and fun. Together, these artistic projects illustrate that both creation and destruction cannot only be housed in the same artist, but that both can be complementary to the art-making process.

Recipes for Disaster is a commentary on technology’s role in not only documenting a tragedy, but also glorifying it. MacDonald, an artist with a degree in journalism, does this not by photographing events that have taken place, but by creating the destructive events himself. By crafting scenes with small-scale sculptures, destroying said scenes, and then photographing the aftermath, he assumes all roles in the staged tragedy. MacDonald states, “I constructed and photographed miniaturized landscapes of domestic environments exploding, that reflect our insatiable appetite for sensationalized images of violence and destruction.” With this series, he is the creator and destroyer of worlds, and the effect is disturbing and powerful.

KABOOM, archival inkjet photographic print

In the piece, Kaboom, the viewer is presented with what appears to be the aftermath of an explosion. A raging fire consumes shattered furniture and household items, producing a thick, billowing, black smoke. There is so much broken furniture that it almost appears to be a heaping mound of trash or the scene of a landfill fire. While no figures are depicted, surely this must have been someone’s home or even the remains of an entire neighborhood. There are more questions than answers, and the viewer does not fully comprehend the events depicted. This uncertainty, this lack of detailed information, is intentional. Of his creative process, MacDonald explains, “I use repetition or patterning to contrast the static forms, in order to create both a sense of order and confusion.” The viewer craves information—the details, the cause, the reasons why—and he or she is denied.

Dedicated to Walk Disney, archival inkjet photographic print

Recipes for Disaster highlights the surreal nature of catastrophes, manmade or otherwise, especially when broadcast through technology’s filter. Objects are destroyed and are almost unrecognizable. Scenes blend and swirl into a whirlpool of chaos. MacDonald alters the photographs digitally to heighten the drama and magnitude of these tragic landscapes. It is an observation of the disposable nature of human existence and technology’s role in documenting this terrifying fall from grace. MacDonald explains, “Although these created sets are from my imagination, the nightmare these photographs represent is not far from the images I see on the nightly news or in the movies.”

detail of Dedicated to Walk Disney, archival inkjet photographic print

How does one reconcile this fascination with tragedy? Is it even possible?

Reconciliation is possible and Forrest MacDonald has found a way. With his Wired Up sculpture series, he steps away from the camera and lets the sculptures speak for themselves. Instead of acting as props decorating a set, the sculptures take the leading roles and seem to communicate directly with the viewer on the artist’s behalf. Two dimensions become three, and the barrier between tangible and intangible begins to fade. The viewer craves information—the details, the cause, the reasons why—and he or she is rewarded.

Homage, archival inkjet photographic print

The Wired Up series consists of seven characters that have such vibrant personalities, one might think they are alive. They are assembled from seemingly random pieces and parts in such a thoughtful way that the result is not simply humor or whimsy, but downright joy. These inanimate objects have the power to reaffirm the viewer’s humanness in the best possible way. While MacDonald used the photographs of the Recipes for Disaster series to “display the fragile and transitory nature of existence” through destruction and devastation, the Wired Up sculptures illustrate the beauty of second chances and new life through repurposing and creation.

Linda looks like the distant relative of a Giacometti sculpture, with rainbow-colored wires that shoot out from her arms like rainbow streamers at a child’s birthday party. The wires extend into long tendrils that reach out to the viewer in a welcoming embrace, as if he or she is a long-lost friend. Karl is assembled from assorted gears and wires, has a body crafted out of coiled telephone cords, and rides a skateboard. Suri stands atop a contraption that looks like an action movie-style bomb, complete with a timer and a comical light-up arrow. She proudly holds up a piece of glass, that could be some sort of lens, as if handing it to the viewer.

Linda, mixed media

These characters are alive and they encourage the viewer to celebrate life and creation, instead of marveling at death and destruction. Old, broken, rejected objects are not waste for Forrest MacDonald. On the contrary, they are the elements needed to create life. He states, “In each piece, my attempt was to reuse a personal, broken item—laptop computer, blackberry phone, robotic vacuum, etc.—and turn the fragments into a figurative, whimsical character.” By utilizing broken objects intended for the landfill, upcycling becomes a means of regeneration. The disposable becomes integral and the discarded items are forged into figures with names and personalities.

The Wired Up series assumed an added level of viewer involvement when it was included in the public art event, Art in Odd Places, in November of 2016. In the streets of Downtown Orlando, the Wired Up characters welcomed strangers to the art-making process by providing an interactive opportunity. MacDonald fashioned columns out of PVC pipes to act as pedestals for his characters. These columns were then wrapped in paper depicting black-and-white graphic novel-style images. Colored pencils and markers were made available, and passers-by were encouraged to color these images. The result is a magical synthesis between artist and viewer as both came together to create the artwork.

Suburbia, archival inkjet photographic print

MacDonald admits that including the viewer at an elevated level of interaction was simultaneously frightening and freeing. He elaborates, “It challenged me to get outside of my comfort zone and engage strangers to talk about art. It was also challenging to let them affect my art. It was both liberating and terrifying.” By offering the opportunity to help in the creation process, MacDonald empowered the viewers to become active participants in the art-making process itself. He provided the creative instruments and the “blank canvas,” and asked strangers for help in continuing the work he started. This is a bold and radical statement for the population at large. In that nontraditional and public setting, his sculptures became a sort of performance piece, requiring humans to engage with each other to create the final work of art. He removed the final boundary between Artist with a capital “A,” and the everyday person who claims that they cannot even draw a stick figure.

The artist has found a way to shift the viewer’s perspective from its obsession with tragedy and gore to the celebration of life and the joy of what is possible. He recognizes the need for balance in all things, even when the viewer does not. Does this suggest a subtle rumbling in the universe of a change in society’s fascination with the macabre? Frankly, it does not matter. Through his artwork, MacDonald is tipping the scales and bringing a sense of equilibrium to the ideas of destruction and construction. In his hands, the disposable is reclaimed and is given a new life. He sees to it that technology not only perpetuates tragedy and disaster, but also bliss and celebration. Forrest MacDonald understands that art requires death and destruction to balance life and creation, and he embraces the gravity and the power of being an artist: the creator and destroyer of worlds.

You can see more at: ForrestMacDonald.com