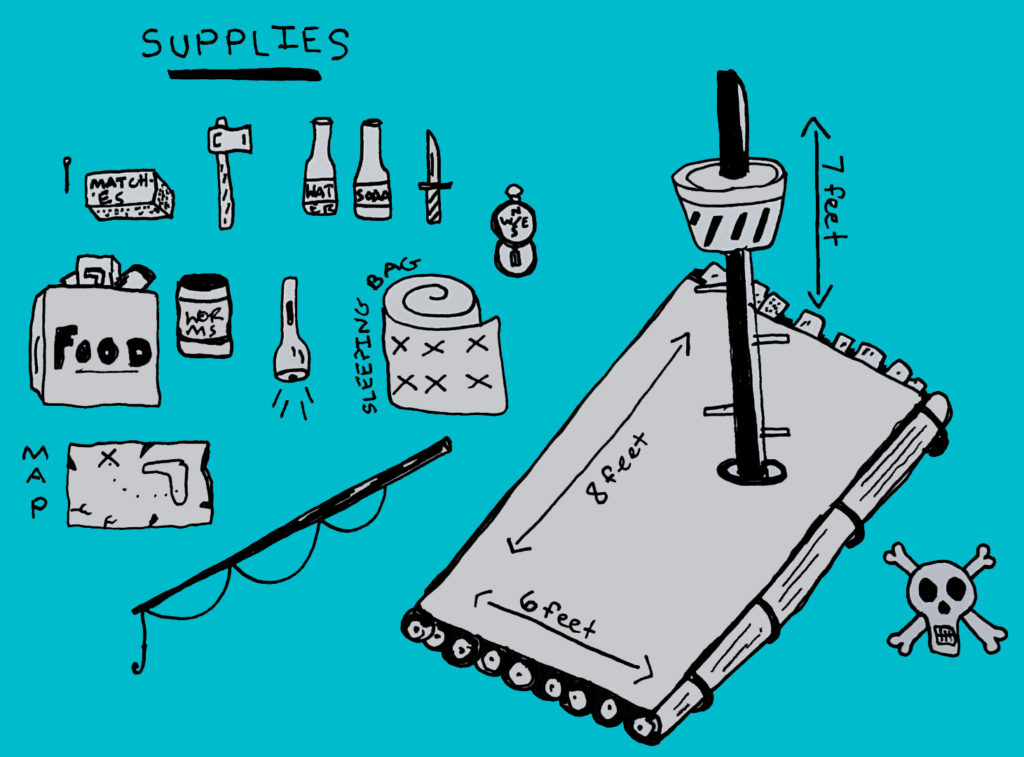

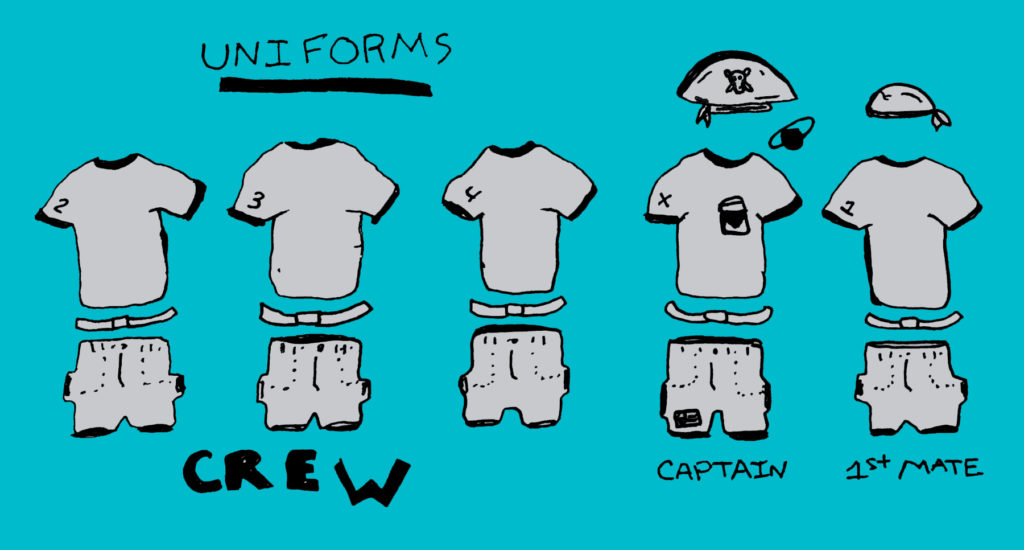

When I was eight years old, I organized the neighborhood kids on a project that I was sure would change all of our lives for the better. Using discarded boards from picnic tables and other junk, I decided that we would build a raft much like Thor Heyerdahl’s Kon-Tiki, which Heyerdahl took from Peru to the French Polynesian islands.

It took us a few days to build. When it was finished, we carried it to a lake and it immediately sank. I’m sure my parents were not only relieved, but also unsurprised. I had told the kids in the neighborhood that when we were finished, we could get one of our parents who had a truck to take us to St. Petersburg from our Winter Park home, where we then could take the boat to New Orleans. When I asked my father later why he didn’t try to stop me from doing such an outlandish thing, he said I figured it would sink, and if it didn’t, then we would need to talk.

At the time, I hadn’t read Heyerdahl’s book, but it was one of many books sitting on my grandmother’s bookshelves. She had talked about the book. In my mid-20s, I stayed at her house for about a month and finally read the book. Her house was filled with books, globes, maps with pins in them indicating that she had been to the pinned part of the world.

My mother, brother, and I spent about eight months living in Plantation, Florida with my grandparents. During those eight months, I attended Plantation Middle School. I was a sixth grader. My grandmother, Edee, was a columnist for the old Fort Lauderdale News. My step-grandfather, Joe, was a sports reporter for the paper. Every morning they would sit on the back porch reading the Fort Lauderdale News and the Miami Herald papers that were delivered to their house. They would smoke cigarettes, drink coffee, and discuss current events. I would sit out on the porch reading, too, and discussing what I’d read. My grandmother insisted that everyone should get up in the morning and read the daily paper and stay informed. I had no problem with that idea.

During my brief stay with my grandmother in my mid-20s, she had stepped up the newspaper delivery to include the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. My step-grandfather, Joe had passed away a couple of years before. Edee (everyone called her Edee) and I would sit on the back porch—that now had a screened in swimming pool—drink coffee, and read four newspapers every morning.

I lived a few miles from Edee for about a year. She would always be willing to go see a foreign or independent film with me. We exchanged books. When I think of John Kennedy Toole’s “Confederacy of Dunces” I think of this period. Edee, my father, and I all read it around this time.

When I was a kid living with her, I remember saying something about how I hated some group of people. She asked me what I hated about them. I gave her a vague blanket answer. She countered everything I said, and pointed out that I was too smart to say things that were not thought out. She asked me to think about what I say—really think about it—and if I think hate something, I should only say I hate if I can give a real reason for hating it. I think about this conversation every day.

When I was in the 7th grade, we moved back to Winter Park, Florida. A neighbor of mine had every Beatles album and 45 ever made. The Beatles had broken up a year earlier. We listened to the collection over and over. Then, I bought some Yoko albums. She had been vilified by most Beatles fans for breaking up the lads. At that time, her role in art movements like Fluxus seemed to be dismissed as crap by all of the Beatles fans that I knew. Her records were the strangest things that I had ever heard. My friend seemed almost angry that I was intrigued by her. I kept thinking, “Wow, someone did this.” It made me feel like any art form was valid. Then I’d read that John Lennon had started listening to composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen and John Cage, because of Yoko Ono. I would go to the Winter Park Public Library and check out albums by these two, and others that I knew were on the Lennon’s list. I would listen over and over, wondering what I was missing. In my 20s, I started to read a lot about these composers and other 20th century classical composers. It started to make sense. I really enjoyed them and became obsessed with the quest to find more.

Lennon, Bowie, and others had also referenced The Beat Generation. I loved the sense of adventure and coolness of the Beats. They were also world class name-droppers who led me to appreciate the other Beats along with Dostoyevsky, Genet, Henry Miller, absurdist theater, Rimbaud, Baudelaire and French Symbolism, Thomas Wolfe, and many others along with Bebop jazz. Reading the Beats led me to Ken Kesey, Hunter S. Thompson, Joan Didion, Tom Wolfe, and the writers who wrote about 60s and 70s counterculture. I guess this article requires me to be a world-class berkau.*

The Beats also led me to explore Jackson Pollock then the rest of the New York School Painters. Like the Beats, this was pretty much an all-male club—or at least the men got the recognition. Pollock’s wife, Lee Krasner, was very talented, but was usually referred to as “Pollock’s wife.” The women associated with the Beats, like Diane di Prima, Anne Waldman, Joan Vollmer, Edie Parker, and several others were given less press, too. I knew that two strong, brilliant, and very talented women were at the root of my autodidactic path: Yoko Ono and my grandmother, Edee Greene.

During my research of the New York School Painters, I realized that there was a group called the New York School Composers, and that Cage was a part of that, along with Christian Wolff, who first gave him a copy of the “I Ching.” Morton Feldman and of course several others were included in this group. This led me to the New York School Poets, and then the photographers.

The Beats, and the Lost Generation—which included Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, Fitzgerald, Isadora Duncan and a long list of others—inspired me to travel. Somerset Maugham’s “The Razor’s Edge,” along with friends like my boyhood friend Mark Imhoof, made me think it was okay to travel without real purpose, or even money. Traipsing through Europe, the Middle East, Northern Africa, Latin America, and all over the United States, it is almost impossible not learn about history, art, food, and see for yourself what people who you have only ever heard about are like. Mark used to say the hardest part about travelling is getting out the door.

I’ve always looked at mentors for self-educating. I guess it’s not quite “self.” I met my good friend Matt Gorney in the mid-80s. He knows more about music than anyone I’ve ever met. He used to be in a band around that time called Bad Afro Experience. I lived in a house downtown Orlando that was, I guess for the lack of a better word, pretty bohemian. Matt would pull up in his mid-60s Corvair with a stack of records most days. We would listen to whatever he put on. There were plenty of stories, referencing, and cross-referencing that went along with these listening sessions. I realized some of what I already liked—The Lounge Lizards, Sonic Youth, and others—were a part of what is called the New York Downtown Scene, and they were a part of the No Wave Scene. Matt has given me countless tips on books, magazines, and music to check out. Later, I was part of the rotation of his radio show, Jazz in the Bible Belt.

While I was living at that house, one of my roommates, Shannon Zimmerman, and I would be on a constant book and periodical exchange, and together, we would seek out material that neither of us knew little or anything about.

Jeff Knowlton, another member of Bad Afro, was often at these listening sessions, along with Mark Greenberg. Jeff ended up getting his BFA and MFA at CalArts. I had never heard of the place until he got accepted. We would frequently talk on the phone. He told me about several different artists, movements, and gave me reading lists. This was around 1990. I found out that schools like CalArts were focusing more on theory. I started to read Derrida, Baudrillard, Lacan, Foucault, Sontag, Deleuze and Guattari, Lucy Lippard, and other dominant theorists. Jeff helped me get a strong grasp on contemporary art.

Mark Greenberg introduced me to the world of photography, and lots of interesting music and films. I continued to find people who could lead me on my quest to learn. I am careful not to take anyone too seriously, or not seriously enough.

Since that time in the early 90s, I’ve continued to search, and have met so many “teachers” that I don’t have the word count to list. Some of them are real teachers, meaning they get paid to teach, but they weren’t paid to teach me.

At the end of the 90s, I was roommates with a real teacher, Steven Garnett. It was more like an extended artist’s residency. We exchanged books, music, watched films, played music.

I barely mentioned any formal education, because the most important things I’ve learned have been out of school. I’ve told people that I never really liked school, and a lot of times they would respond, “Oh, I do.” I love to learn, but sometimes school seems to get in the way of my idea of a path or paths. I’m really surprised at how many art history students seem to know little or nothing about contemporary art. They usually tell me they start to learn that in grad school or at the end of undergrad. This is the kind of thing I didn’t like about school. I wanted to learn about what’s happening now, and then find out about why artists do what they do now. I had teachers try to keep me from reading something that they thought wasn’t important, but I credit listening to rock music with being a big part of what led me to learn about jazz, classical, photography, conceptual art, performance art, literature, film and even hiking (“The Dharma Bums.”)

I realize that my father had a bigger intent when he let me build the raft. He didn’t want to quell a misguided enthusiasm, because he knew that it was not only harmless, but the enthusiasm was rooted in a curiosity for the world that has never stopped.

*A name-dropper.