Back in February, I was organizing papers at Gary Bolding’s home studio when I came across a typewritten resumé of his as old as I am. The first page of the yellowed papers, still neatly clipped together, included the addresses and telephone numbers of just three people: Philip Pearlstein, William T. Williams, and Allan D’Arcangelo. The list of names reads more like an upcoming group retrospective at MoMA than a graduate’s references. I knew Pearlstein had been one of Bolding’s professors, but to discover these heavy-hitters of the art world on an unassuming document really reminded me that, regarding my educational lineage, I’m from good stock. As a former student of Bolding’s, and his current model and assistant, I consider myself fairly close to him. Though I feel much like one of his kin, I’m unremittingly learning new things about his multifarious past. I recently had the chance to ask him a few questions that came to mind when considering the gaps in my knowledge of his artistic career.

Stephanie D’Ercole: Why art?

Gary Bolding: I don’t remember not drawing. Reams of typing paper and pens and pencils from my father’s office were always at my disposal. I found making art an amusing way to spend time.

I never thought of myself particularly as an “art kid”. I never took an art class except for one in the seventh grade. I was interested in all kinds of stuff: reading, music (British Invasion and Memphis Soul), science, and sports. I was consistently drawn to almost any kind of creative pursuit. Upon reflection, I guess most third graders don’t beg their parents for sets of oil paints and then copy reproductions of Van Gogh paintings from the encyclopedia, but at the time I didn’t think it was abnormal.

My parents were intelligent, practical people who had lived through the Great Depression. I was raised to be a doctor, lawyer, or engineer. Being a professional artist of any kind was never a consideration. I had been an excellent student until my later teenage years when I became interested in things other than schoolwork. In college, I was a dilettantish slacker drifting from one major to the next. I played guitar and wrote songs, but was terribly self-conscious about performing in public. I continued to paint as a hobby. When I was a junior in college, I took a painting course thinking that I might as well get academic credit for something that I was doing anyway. Filled to the brim with the unearned arrogance of youth, I remained a stubborn autodidact, but was allowed to earn an art degree in my remaining four semesters. After spinning my wheels for a few years, I moved to New York City with my future wife, Jane. I studied at the Art Students’ League, The New York Academy of Art, and Brooklyn College, and I immersed myself in the city’s galleries and museums.

So, why art? A life centered around a creative practice was appealing to me in a way that nothing else was. It is that simple.

You have mentioned Meet The Beatles as your first introduction to art. Do you mean both visual and musical?

Yes. Meet The Beatles was the first experience of art that I remember. It probably has to do with the work having been done in a medium that can be infinitely reproduced without becoming pale shadows of themselves, like the plates of paintings in books. Like a Coke, my copy of Meet The Beatles was just as good as that of a kid who grew up across from the Met. I was always interested in making art, but this was different. This was being swept up in the creative work of someone else.

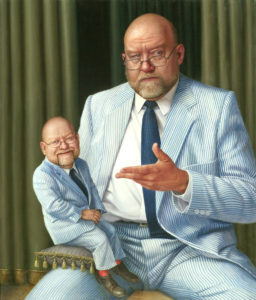

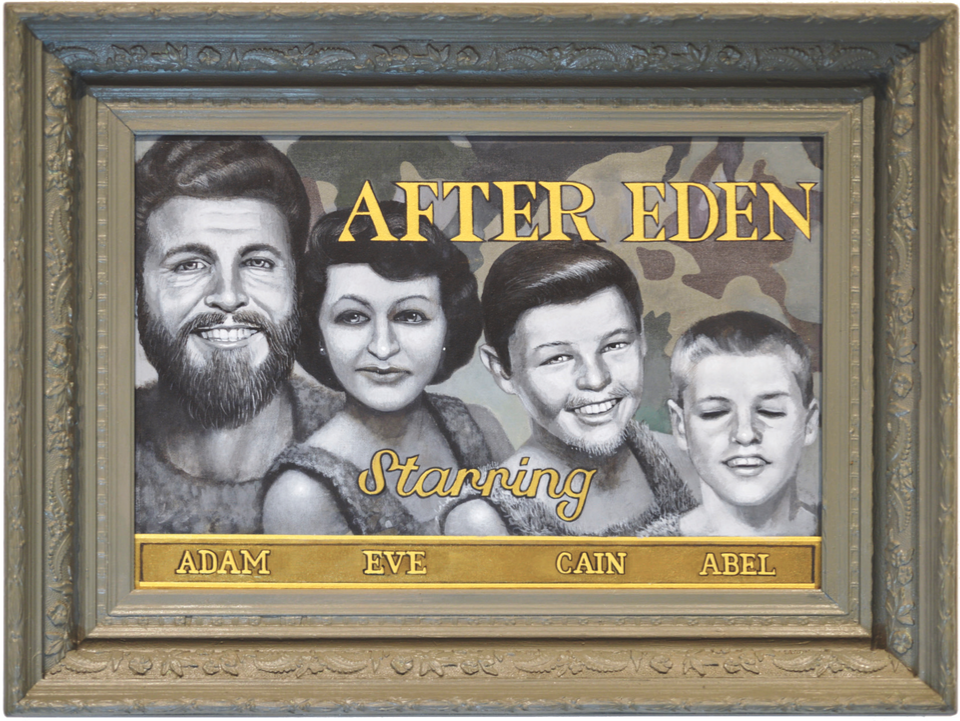

Double Self Portrait

What was the flow between your representational paintings and your abstract ones? Did you break away from representational painting to do abstracts for a certain reason?

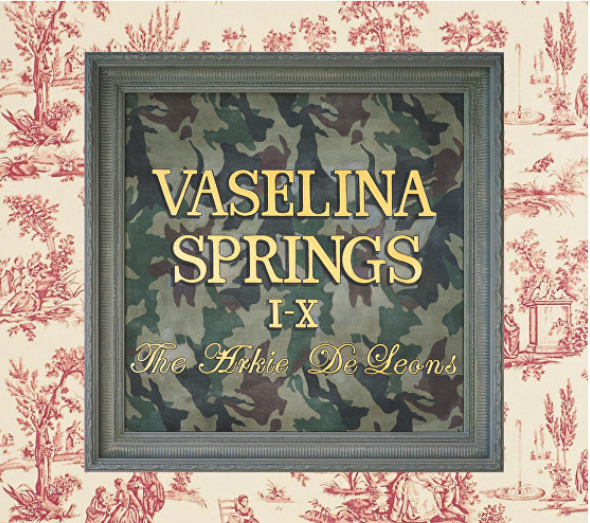

The change was not strategic or intellectual. It felt like it happened at the cellular or molecular level. After I finished Double Self-Portrait, it was as if a switch had been thrown. I was done with that kind of painting. The practice of describing my subjects in minute detail—something that had once so engaged me—now seemed not only torturous, it seemed predictable. I was ready to try something I didn’t know how to do. I was ready for a new experience. Oddly enough, I am now employing some of the technical approaches that I used to make abstract paintings to make the new, large, representational Vaselina Springs paintings.

Were the abstract works a revisitation of an earlier artistic sensibility?

I started exhibiting in my early 20s as an abstract sculptor and painter. I then became a figurative painter in NYC after studying figure drawing for several years. Despite this change in orientation, my interest in artists like Cy Twombly and Richard Pousette-Dart never diminished. When I returned to abstraction, I struggled with the problem of how to structure a painting that has no image, but I loved the act of painting itself. Focusing on the physical properties of the paint and on different ways of manipulating it gave me great pleasure.

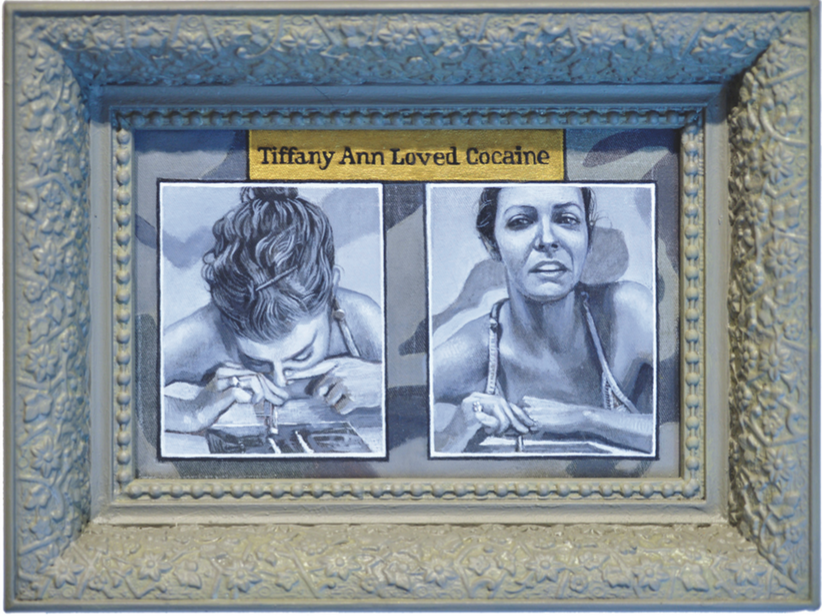

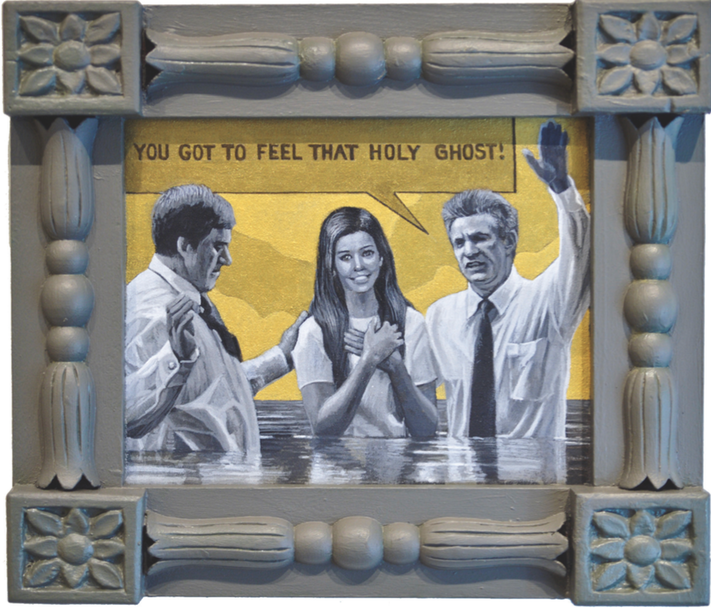

Do you see yourself pursuing something beyond Vaselina Springs, or are you too honed in on this project to think about what you’d like to pursue post-Vaselina?

I don’t see an end to the Vaselina Springs project. It appears to be inexhaustible, plus it allows me to do so many different things under its auspices that I don’t see it becoming monotonous. I do have one non-Vaselina Springs project in the pipeline. For 2016, I am doing an artist’s book project involving daily readings of the poet Rainer Maria Rilke. This has proven to be incredibly meaningful to me. I plan to begin another daily project in 2017.

You can see more at: GaryBolding.com