Driving west on 98 towards 441, I did a loop through Pahokee and Belle Glade. It’s not the fastest way back from Ft. Lauderdale to Orlando, and that didn’t matter. It’s one of the most interesting ways, and that did matter. The area felt foreign but familiar—the feeling that I get when I drive through the back roads of Florida—and it felt like I might be in Latin America or the Caribbean. Signs are in Creole, Spanish, and English. No chain stores for a while.

It was September 2009. My father had passed away a couple of days earlier. He made it to 74. He had a long history with drugs and alcohol. My brother used to say that it looks so healthy when he had a glass of fresh squeezed orange juice and cheap vodka with his breakfast. On the way out of Ft. Lauderdale, where my father died and had been living since the early ’70s, I stopped at Cracker Barrel with my cousin Julie and my aunt Helen. We all exchanged stories about my dad. We repeated many that we all knew, and we all had some new material to offer each other. Julie told me about the time when she really wanted to go see our grandmother, Edee, in New Smyrna Beach. Julie was only 15 and didn’t have a way up there from Ft. Lauderdale. If she got there, she could ride back a few days later with Edee. My father offered to take her. Julie recounted how, what would normally be a ride that lasted a little over three hours, took over seven, and how they ate boiled peanuts, and he took the back roads, and told stories about old Florida.

I left Pahokee, and headed north on 441. The sun was shining brightly, and the rain started to come down hard, yet the sun continued to shine. My visibility wasn’t good for a while. The rain suddenly stopped. I could see. Steam rose from the misty road.

My father told me stories every time I was in the car with him. This was the kind of backdrop for him to tell his best stories. His stories were often heavy with historic figures, and ulterior motives by those figures. Many times they were set in the location of wherever we were driving. It felt like I was watching a documentary while also being a part of the documentary. I would soon be passing Yeehaw Junction’s Desert Inn that was once a brothel frequented by ranchers. He loved pointing that out.

Julie said that after my father dropped her off at my grandmother’s place in New Smyrna, the three of them ate dinner. My father decided to drive back to Ft. Lauderdale. I’m not sure exactly where he was when he was pulled over by the highway patrol, but I think it was somewhere near Mims or Geneva. It turned out the real motivation for taking the back roads was that he was driving a stolen car. He was taken into custody. I don’t remember him doing any time for this, so I’m not sure what came of it, but the story didn’t surprise me. I’d always pictured him being pulled over near Geneva. I don’t know if I was told that or if I imagined that. Geneva would be the best place for my father’s arrest. It has readymade backstories.

Ft. Lane Park is in Geneva off Highway 46. The park is named for Colonel John Foote Lane. He was a colonel in the second Seminole War. His post was Fort Drane, just north of Ocala. Formerly, he had been a math and philosophy professor at West Point. He had entered West Point as a student at age 13, and graduated when he was 18. He is also believed to be the inventor of the modern day pontoon boat. In 1836 he contracted encephalitis while stationed at Fort Drane. This caused him to go insane, and he put a sword through his head into his brain, ending his life.

I don’t know of any evidence of him ever setting foot in the area that is now named for him.

I imagined my father driving down Highway 46, telling 15-year-old Julie this story while they shared boiled peanuts and he sipped on a beer.

In 1992, a skull was discovered in the Smithsonian Native American collection. At the time it was identified as skull number 2244. Later it was discovered that it was Lewis Powell’s skull.

Powell had been involved in the Lincoln assassination conspiracy. Powell, alias Lewis Payne, was supposed to take out Secretary of State William Seward, as part of a holistic slaughter designed to knock off the top of the chain of command. At the time, Lincoln was the president, and Andrew Johnson was the vice president. Seward was stabbed in the face by Powell’s bowie knife, ending up disfigured but living seven more years and serving as Secretary of State to Andrew Johnson. Seward is known more for his role in the purchase of Alaska from Russia.

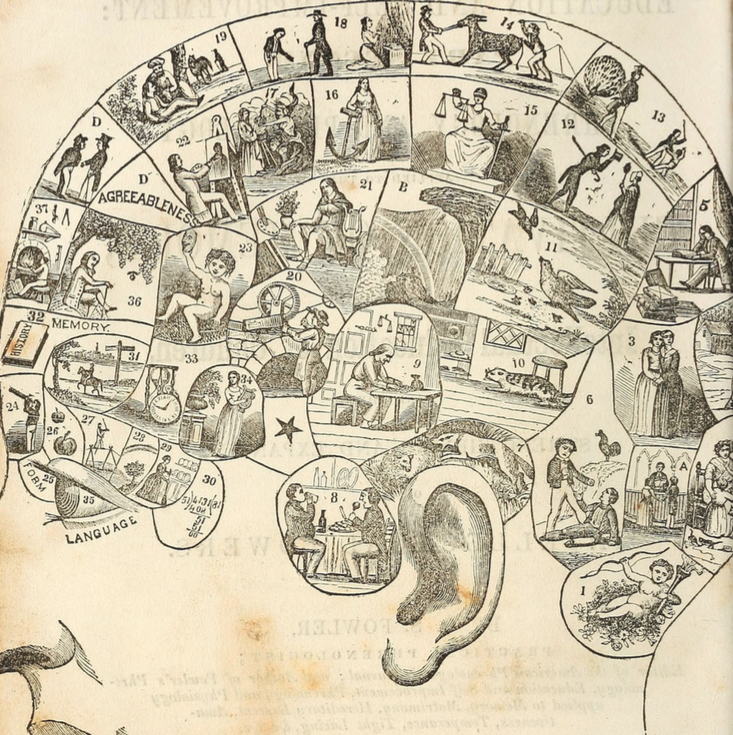

Johnson also survived after George Atzerodt failed to follow through on his assignment to kill Johnson. Atzerodt wandered drunk through the streets of Washington D.C., throwing his knife onto the road. John Wilkes Booth was the only of the three who succeeded in his assassination. Powell and the other conspirators were hanged a few months later. Powell was a Confederate soldier. He and fifteen other Confederate soldiers, and one Union soldier, are buried in the Geneva Cemetery. Powell’s skull was reunited with the rest of his body in 1994. It had been handed over in 1898 by the Army Medical Museum after traveling from a few different grave sites. Meanwhile, his body was buried next to his mother in Geneva. It turns out that an undertaker separated his head from his body in 1869. I’m not sure why. His family had come to Washington to pick up his remains in 1871. I’ve heard stories that a phrenologist had taken it to examine. Phrenology was popular at the time, but the story is unsubstantiated. My father loved the phrenology angle, but he didn’t present it as factual—only as a theory.

These two Geneva stories were favorites of his. He talked about how these stories are the kind of stories that kids need to hear to get them interested in history. I passed through Lake Okeechobee. Highway 441 was desolate. I started to think about transporting Lewis Powell’s head. Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia flashed into my mind. I thought of Warren Oates’ character in the film. He was an itinerant piano player transporting a decaying head through Mexico in order to collect ten grand, encountering bombastic bikers, prostitutes, and lots of gun-happy characters, along with Peckinpah’s slow-motion violence. This area reminded me of Warren Oates driving down a Mexican highway with Alfredo Garcia’s head, the scenes where Garcia’s head fell out of the bag to the ground and rolled around while flies hovered over its circumference. Garcia, who is never seen in the movie, allegedly impregnated the daughter of the crime boss he worked for. The crime boss put a bounty on his head, in the most literal way.

Both men’s detached heads became sought-after vessels that reduced their lives to specific incidents, which led to their deaths by very unnatural causes.

My father had been cremated. In his will, he asked family members to distribute his ashes into the Banana River in New Smyrna. None of us could figure this out. I didn’t know of any strong connection to the place. I surmised it was either a joke that only he knew about, or maybe he had smuggled some pot there in the ’70s, or fallen in love there one of the many times he said he fell in love.

My aunt Helen insisted on a Christian ceremony. A few of us read Biblical passages that she chose. I wanted to read a Bukowski poem or something that I thought was more representative of my father. I liked the idea of mixing that up with Biblical passages, but my aunt didn’t like the idea. It didn’t seem like the time for confrontation, so we compromised. I handled the Communion ceremony. I mixed freshly squeezed orange juice and cheap vodka into a classic, patinated Stanley thermos. For the wafer, we ate Triscuits. He liked Triscuits with peanut butter. We had them plain. My brother threw his ashes into the Banana River.

About a year later, I was driving on a back road that connects to Alt. 19, just north of the Tarpon Springs Bridge. It was late morning. I saw a casket next to the dumpster of a warehouse. I forgot how big those things are. It looked about eight feet long, made of white metal. I didn’t get out and touch it or open it like some of my friends suggested to me later. I called my friend Alex. He said I should throw it in the back of my hatchback and ride the two hours to Orlando with it sticking out. I ignored his suggestion, but thought about it a little when he mentioned selling it on Craigslist. I wondered about the history of the casket, and how it ended up empty next to a dumpster. I thought about how most people pass through the world fairly anonymously, and how many stories will never be heard. The processor in a computer is often called the brain of the computer, but there is still so much more we hope to learn about our own brains. So much of who we are is not visible—our interior life, our brain, is still mostly an unexplored frontier.

I made my way through Tampa, back from Tarpon Springs, towards Orlando. I stopped and got some guava pastries at the huge twenty-four-hour Cuban bakery in Seminole Heights. After that, I headed down the street to Nicko’s Fine Foods diner. It’s an authentic Greek diner. It looks like it was manufactured by Airstream. I ordered a Greek omelet and a cup of coffee. I read The New York Times (hard copy) as I ate. I noticed a man who looked to be of college age sitting across the table from a woman who looked to be about 35. She had a folder, and kept pulling out papers that she seemed to be reading from while talking to him. It looked like she was his caseworker. I heard bits and pieces of their conversation. She was looking at X-rays. I heard him say, “I can look at a copy of my MRI and tell you exactly what part of my brain is missing.”