AfroFantastic: Black Imagination and Agency in the American Experience is up now at the Cornell Fine Arts Museum on Rollins College campus. Professor Julian Chambliss, Ph.D curated the show in conjunction with students from his AfroFantastic class. Chambliss and I got the chance to sit down and talk about his inspirations for the show, how he went about the curation process, and what it was like putting together his first visual arts show in a museum setting.

Chambliss worked on the AfroFantasic show as a part of a class called AfroFantasic. It is an experimental class that students can take at Rollins; it’s the first version of the course and he’s hoping to work it into the mix. I’m interested in knowing if Rollins could provide this class free of charge to black people and people of color. The students in this class helped to write the wall text/didactic after extensive research. Afrofuturism, part of the concept for the show, is a literary and cultural aesthetic movement that depicts a black-centric future while incorporating science fiction themes, historical fiction, magic realism, and strife experienced by black people and people of color. The term was coined in the 1990s but it retroactively identifies different moments in history where Afrofuturism was, in a way, being conveyed. The AfroFantastic exhibition is looking at the black imaginary since the nineteenth century: “The black imaginary is a space of empowerment and agency.” Chambliss is also heavily influenced by graphic novels—you’ll see a lot of this aesthetic inspiration in the show. The counter-narrative of white expectations and ideologies like post-colonial theory are also recurring themes in the show.

What does black art look like in a white cube gallery setting?

Who’s the audience, the primary gaze?

What does a black-centric future look like?

There are expectations of black artists from the art world that create trends within the community. I see these trends amongst my peers, at art galleries, at art fairs, and in museums. I also experience this type of questioning when it comes to my own practice (both of my parents were born and raised in Cape Verde, a country off of the west coast of Africa) although the experience is slightly different from African Americans (only because our country was ruled by a different group of white people, the Portuguese). These questions do come up after I find myself making empirically charged, identity-based works because this is the work that gets the most response.

Exhibition view of title and case.

After getting the backstory of Chambliss’ curation process, some Afrofuturism history, and rethinking of all the questions that come up with being a black creative, I went down to the museum to see the show. The large black and red wall text reading “AFROFANTASTIC” is the first thing you see and the first thing that is easy to interpret. The letters remind me of speech bubbles in graphic novels, in the way that they’re all capitalized and are in a minimalist font: the font that is used in graphic novels makes the text legible around images that are full of movement. There are sculpture, illustration, text, audio, and video works in the show, creating an interestingly diverse atmosphere.

The audio file is an eight-minute excerpt of a lecture by Sun Ra, accompanied by an abstract looping video. This immediately caught my attention. I’m interested in ways artists create sounds and display them in visual environments like galleries or museums. The abstract video on loop helps to create the kind of focus needed when listening to a lecture, and the visual also stays true to the Afrofuturist aesthetic. Hearing Sun Ra’s accent and the way he enunciates his words reminded me of the ways black people are discriminated against because of the language we use and the way it can dissatisfy white academics. This piece was a curatorial choice—Chambliss put together the audio/visual installation himself. It creates dimension and simultaneously honors history.

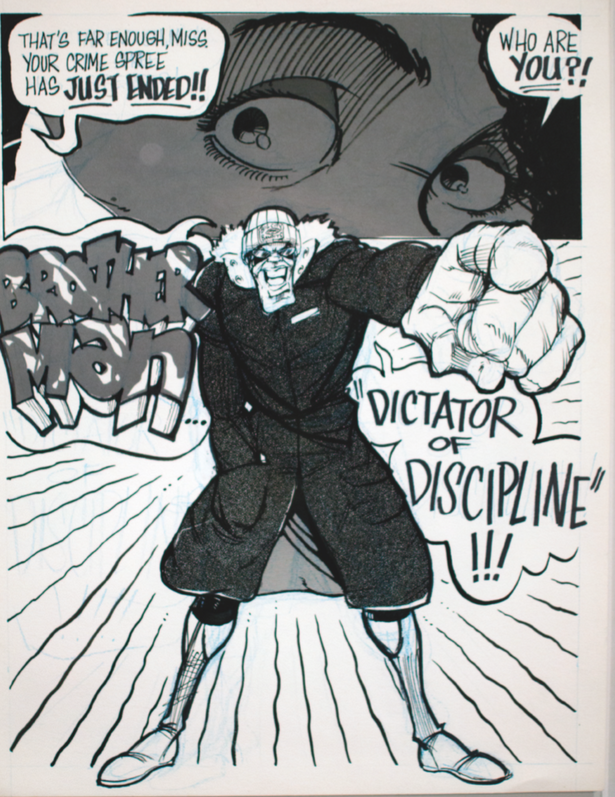

BrotherMan: Dictator of Discipline, by Dawud Anyabwile, Issue 1 pg. 17, brush and ink, zip a tone

My favorite piece in the show is an illustration titled BrotherMan: Dictator of Discipline by Dawud Anyabwile. The piece is a drawing of what looks like a black and white page from a graphic novel; it is displayed next to three similar works by Anyabwile. The style is very reminiscent of comic books from the ’80s. There’s a speech bubble with the word “BrotherMan” written in an almost graffiti-type font, and an accompanying bubble that reads “DICTATOR OF DISCIPLINE.” I’m really interested in images where “violent” language or symbols are placed within the power of black bodies. A black person calling themselves a dictator, to me, does not come across as unnerving—it’s empowering. As history teaches us, white people have always possessed this power over black people and people of color. My favorite example is the first revolving gun, a gun that can shoot multiple rounds without being reloaded, which was invented by a white man just in time for the Mexican War in 1846 and the Civil War in 1861. Legislations like the 1911 Sullivan Act and the 1967 Mulford Act were passed to keep black people from owning guns. The Mulford Act is especially interesting because it came into play after the rise of the Black Panther Party. Seeing Anyabwile’s artistic image of a black person in power is very important.

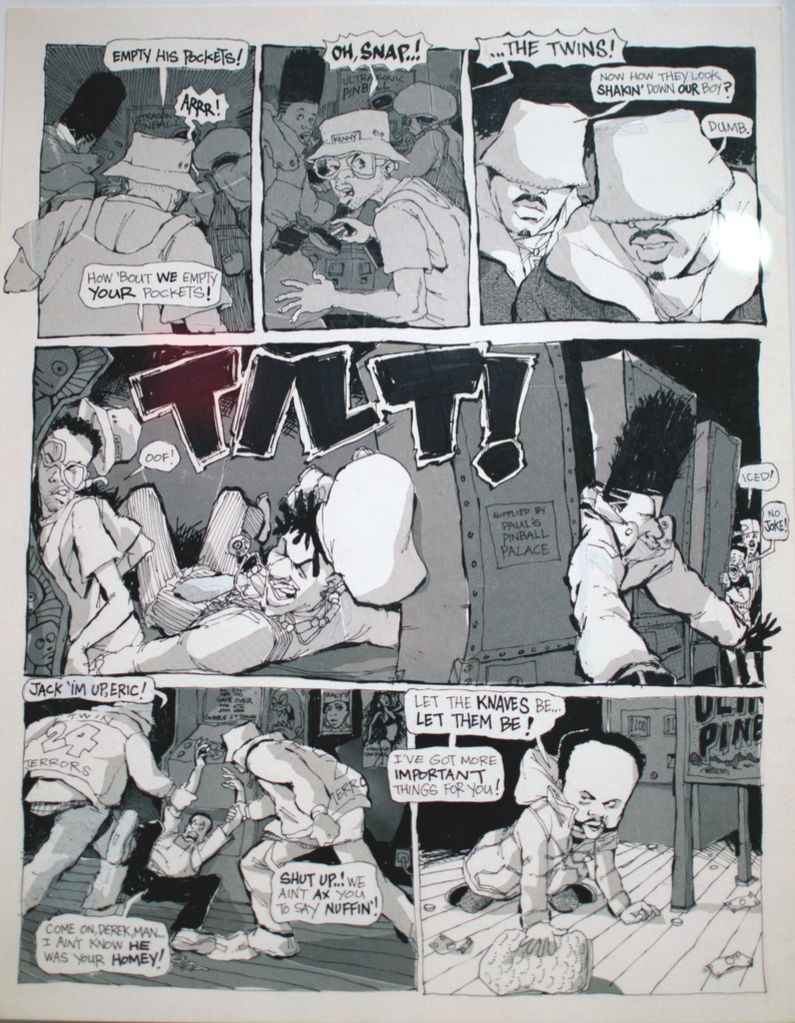

BrotherMan: Dictator of Discipline, by Dawud Anyabwile, Issue 3 pg. 17, brush and ink, zip a tone

Afrofuturism is black-centric, black-centric imagery is power, and that could be seen as violent, but this violence should not be confused with the same violence that has been used against black bodies.

Photos by Mariana Mora

AfroFantastic will be on display through April 2, 2017 at the Cornell Fine Arts Museum located at 1000 Holt Ave., Winter Park, FL 32789

You can see more at: Rollins.edu/cornell-fine-arts-museum