Robert Rivers and his wife, Peggy, have a place in Maitland that looks pretty suburban. The neighborhood is settled down, and Rivers’ home is busy being lived in. A seasonal flag marks the front door, completing their holiday decorations. No permit boxes decorate front yards, no dumpsters are sucking off the sturdy mid-century homes, and the streets seem blissfully out of the path of the tornado of McMansions that has become Central Florida’s unfortunate zeitgeist of late. In this peaceful setting, I interviewed Rivers in his home and his studio, perched over the garage with late-afternoon winter light filtering in through the windows.

Evil Man, ceramic

The interview was continued digitally and on the phone. It culminated in a dinner with Robert and Peggy Rivers and their colleagues and spouses the Enzian’s Eden Bar. The evening spun into a spontaneous, sometimes raucous, freewheeling debate about art and teaching, occasionally involving the server—one of Rivers’ students—and Ruby, their dog.

Robert Rivers is a Professor of Art with the University of Central Florida’s School of Visual Arts and Design. He teaches figure drawing, advanced drawing, and etching. He has also taught at Edinburgh College of Art as Visiting Professor for part of his career. With exhibitions in Europe and America, critics have reviewed his work numerous times, giving him a unique position in our arts community. He’s talked about.

Rivers uses printmaking and drawing, as well as ceramic, to express his ideas about the darker spirits that lurk in all of us, coming out in both human and animal figures. He has developed a method that offers the viewer an immediate, almost naked contemplation of the meaning of being a human without the protective cloak of civilization. His work is so confrontational to the viewer that writer Henry Walton says of it, “evasion is not an option.”

It was not an option for me, either. The interview started essentially when I was still getting out of the car, grabbing a notebook off the front seat. Rivers stood outside, waving his arms, flagging me down, and by the time I was inside the house with a cold beverage, we were well into the travel books that he has published with Flying Horse Press.

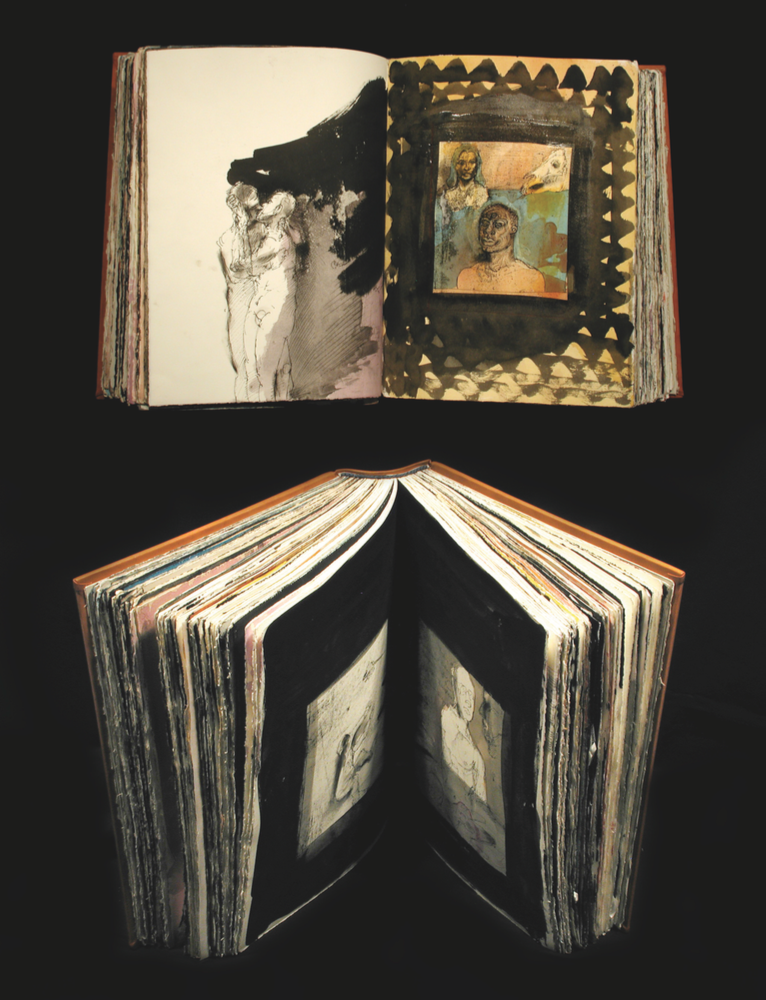

The books are oversized, some as big as a table, full of original drawings, etchings, and paintings on fat, archival paper with live, untrimmed edges. The books’ somber maroon covers belie an energy vibrating off the pages, like undiscovered medieval manuscripts one wishes to pore over carefully, missing not a mark or a line. They also weigh a ton.

Mercy on Me, handbound book (two views)

Rex Thomas: Tell me about these incredible books.

Robert Rivers: Larry Cooper, Rob Reedy, and I started Flying Horse Press. Cooper was kind enough to bind these drawings together in a book. I gave my Patagonia book to Steve Lotz. This book is from another trip, where I brought paper and supplies, sometimes mailing these back and getting some more. I travel with lots of loose paper.

What kind of things do you draw when you are traveling?

[Points to a drawing of a male figure on all fours, its face a profile of arduous concentration]. This drawing is typical—I do these at cafes, on the street, in my room—and try to finish them right then and there, with color. (A swirl of bright vermilion weighs the figure down.) Each trip is, for me, a craving for outside influences that I can absorb and bring into my work. I see things anew when I travel. It causes me to work harder, to get at my subjects from different angles, and gain energy from what I see.

Wisdom of God, etching

You started out with etching, yes?

No! I started drawing first. Then, I studied printmaking with Maltby Sykes and Conrad Ross at Auburn. It was a huge mistake! Etching a plate connected with me in some primitive, reptilian way, and I was physically drawn to the process. Printmaking has a requirement that you pare down, discard the nonessential, and it helped me focus myself down into the little furrows I was making on the copper surface, getting into the gore and the tone of line. It took me some time to find my process then.

Back in the early seventies, Auburn was a “company town” built around the university. The art school was in an old girl’s dorm on the periphery of campus. We felt like a bunch of gypsy outlaws, which increased my fervor to get lost inside art and printmaking. Since it was so small, there was more cross-pollination between students and faculty, and we knew everybody.

UCF was like that when I started in 1980. When I began teaching, I was awed by the professors in the art department—Johann Eyfells, Steve Lotz, Charlie Wellman. I felt like a young punk kid who was always in trouble. Now, it’s grown so huge that we don’t really have that sense of community anymore. So many faculty I don’t even know. Someone recently told me it is the single largest higher education institution in the country now! I guess that’s a good thing, but in some ways the loss of intimacy is sad.

I had to choose a major to stay in college, or I was going to Vietnam. My choices were veterinary school or architecture. Both looked pretty difficult, so I tried art. That is when I met Sykes, Ross, and the other teachers there. Once I learned how to draw from them, I never looked back.

Veterinary school?

I’ve worked with animals all my life. Circus trainer, horse trainer, dog trainer, cat trainer [laughs, as a silvery-gray cat weaves between us on the table]. So I’ve had an intimate relationship with lots of animals as individuals for forever. I also wanted to be a football coach! I enjoy intense physical activity, as well. It is the desire to teach what I know that led me to what I am doing today; it’s all kind of balled up together.

[Referencing a thick copper plate, about 2’x3’] This is one of your last copper plates, yes?

It’s not the very last, but close to it. Here, I wanted to create a classical Greek figure of a horse, and the body is proportioned as an iconic figure. But I often juxtapose a contradictory figure into work, and in this corner, this little ball is a naughty monkey’s head, flayed so its musculature and skeletal form is laid bare. It’s chained. You see both sides of an animal’s nature that way, the freedom and enslavement, good and bad, both inside and outside.

Hercules at Rest, etching

When did you stop etching and turn to drawing?

When a young pony I was training fell on my arm, and bone splinters damaged my ulnar nerve. Holding an engraving point became impossible; I couldn’t control it. So, drawing [shrugs]. (If he felt sorry about the event, he didn’t indicate it. Instead, he pressed on as if a new adventure needed explaining.) It was, in a way, like coming back home. We still do a lot of printmaking and I run the printmaking studio when I can. Drawing, however, released me to explore a visual language that I would not have tried otherwise.

(By now, we’ve drifted up into his studio. At the door, a metal sign says “BEWARE OF THE DOG.” At the bathroom, another sign says “GENTLEMEN.” The studio is open in the middle, with stations for each various parts of Rivers’ process: drawing board, standing easel, painting easel, and couches. His own art hangs on four walls, and a ceramic bust is mounted on the top of a stack of flat files. A television sits between windows which let light in on three sides of the room. Despite a prolific fury of creativity, his tools and the studio itself are highly organized, suggesting an ascetic’s discipline and rigor.)

Laughing Woman, ceramic

Can you share a little about your process?

So, this relationship with animals is what I return to over and over again. In the ancient world, an iconic figure of a lion tearing apart a man has possessed me, and I’ve studied it since I started drawing. This visceral consumption—the lion eats flesh—is a moment of truth. It is an act that has no thinking as its prerequisite. The pounce and the grab. It reduces life to its essence, and this essence is what I’ve sought. Draw first, think later.

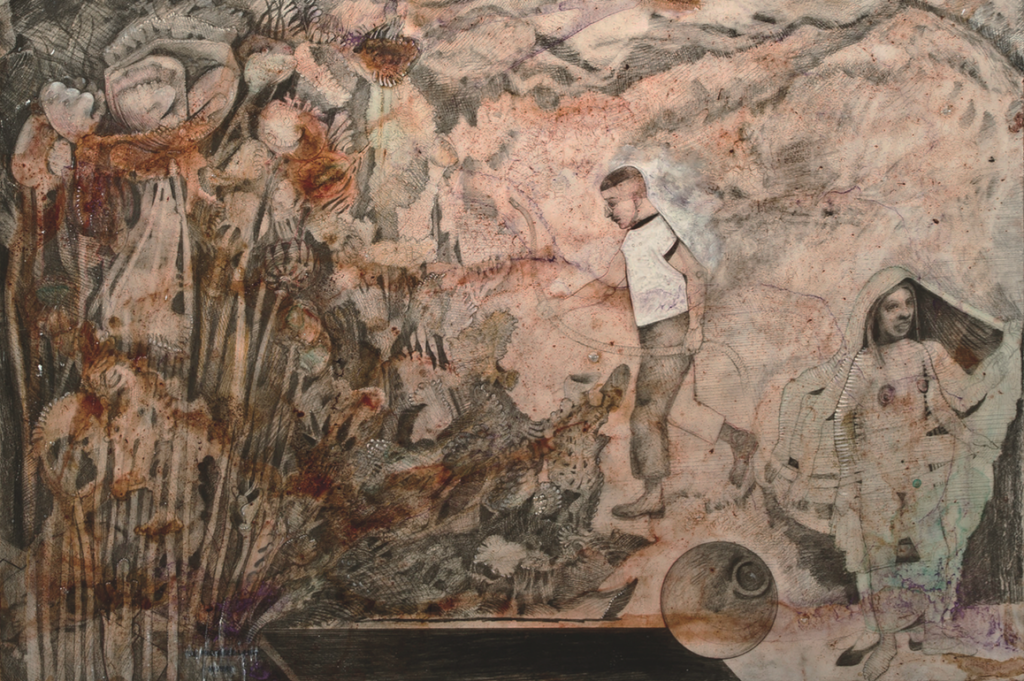

Drawing itself starts often with a classical figure—a man standing, for example. I try to cut down to the essential in my composition. But in the subject matter, I throw in everything I’ve got! When the drawing is done, I wash it with paint; sometimes going through the cycle a couple of times until it is ready. The coating of clear medium adds depth, and sometimes I even draw upon this. This process is stabilized, so I can concentrate on the subject matter I’m working on for now.

What kind of subject matter are you working on now? (Back downstairs, in a spare bedroom, are stacks of drawings, each at least a foot high. You can’t even step around the room.)

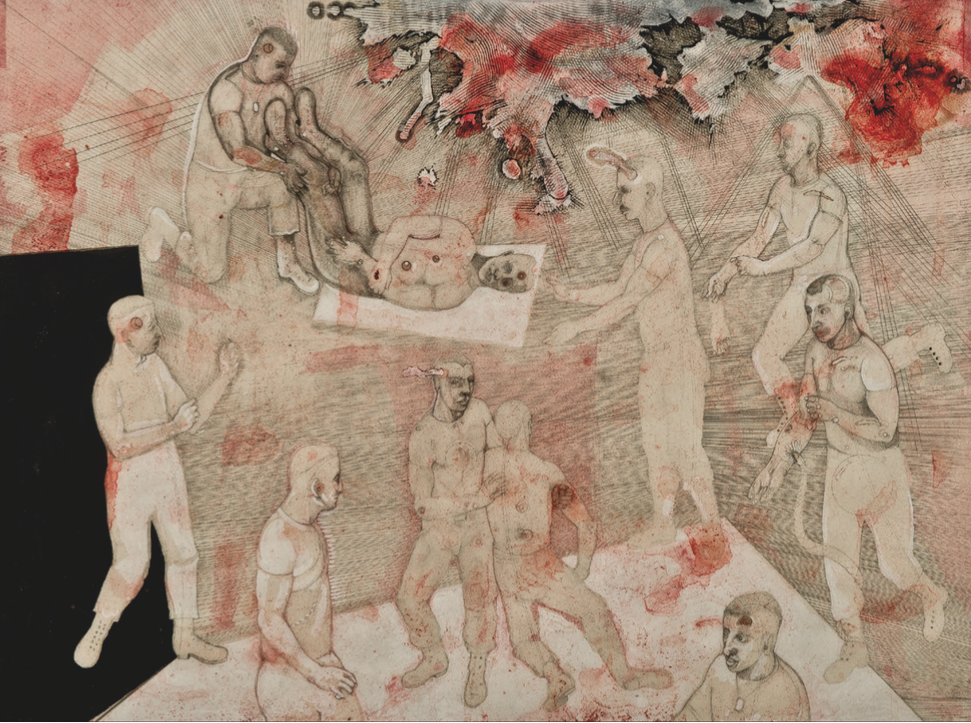

The Promised Land – April is the Cruelest Month, mixed media on paper

My brother asked for a single landscape [gestures, somewhat helplessly, to the stacks of drawings]. It was to be a tribute to his son, my nephew, a soldier lost in Afghanistan in 2010. I’ve entitled this series The Promised Land. I explored the archetype of the young soldier. Into this figure I’ve created the essence of him—here are the boots as a reference to the soldier’s profession. Poppy fields, or the chaos of warfare, surround him. When snakes—or in this one, a shark—appear, they are counterpoints to the lone figure. These compositions explore my feelings around my nephew’s service, and the meaning of his sacrifice.

The Promised Land – Your Arms Full, mixed media on paper

What would you say to a student, or a reader, about art?

Well! No matter what you think you are doing, keep your process fresh. Don’t get bogged down. If nothing has pulled the rug out from under you in a while, pull the rug out from under yourself! In the print studio, I call it the “print gods”—they introduce surprises into the work that you cannot control. It’s OK, but your work must have enough strength to integrate the accident and get better because of it. Don’t let your skill level inhibit your creativity. We’re working here in Central Florida without a lot of eyes upon us, so that is your freedom! Nothing is holding you back from diving deeply; you must satisfy yourself first. As a teacher, I have to make that as difficult as possible—there are no easy roads for an artist.

The Promised Land – April is the Cruelest Month – The Helmand Province , mixed media on paper

The Promised Land – That Lonesome Valley, mixed media on paper

Later, during dinner on a lovely, warm evening at the Enzian, Rivers and his beautiful, elegant wife sat with his colleagues. We talked about horses and art. The question was posed to the table: Who is more important, the artist or the teacher? Teachers, students, and artists at the table all started talking at once. Since everyone at the table both taught and made art, disagreements ran strongly. Answers were decisive: the artist creates the work. But the teacher creates the artist; every artist owes something to a teacher. But everyone ultimately must stand on his own.

Rivers offered his thoughts, “I give my students the classical foundation and training that is needed, so when they go forth in creating in their own chosen medium, their process is informed by the history of that medium. But ultimately, one must act without premeditation.”

Characteristically, perhaps, Rivers avoided choosing one over the other. Like many of his drawings and paintings, the classical figure dominates the field, but a hairy little soul—that unpremeditated act—lurks in the corner with a ferocity that complements the static main figure. Which one is the teacher and which is the artist? The enigma was not answered by Rivers that night, and may be the research of future historians who contemplate his quest to define the identity of man and nature.

You can see more at: RobertRivers.com

Pride Joy, ceramic

Wow impressive!!

I love Robert’s etchings and drawings! I am fortunate to own a few when we traded. I taught etching for 26 years at the Univ. of Oregon in Eugene and often showed his etchings to my students. I especially liked his use of foul bite in etching, used similarly like the red wash over his drawings. I learned quite a bit more about him from your interview. He is truly one of my favorite artists and I value staying in touch with him as a “friend” on FB

Robert is not just an inspiring artist his art also makes you think and question. On top of that he is a wonderful human being– father, husband, friend, animal lover and more Am honored to count our family among his and Peggy’s countless loving friends

Excellent and moving article, Robert…

Rex Thomas has created a fine portrait of you ( at home..in the studio..with friends)

It’s an illuminating piece..and the works chosen perfectly illustrate your imagery and preoccupations.

Your artistic legacy and reputation is secure, at home –and here in Scotland