In the dark times,

will there also be singing?

Yes, there will be singing

about the dark times.—Bertolt Brecht, “Motto”

Svendborg Poems (1939), trans. John Willett

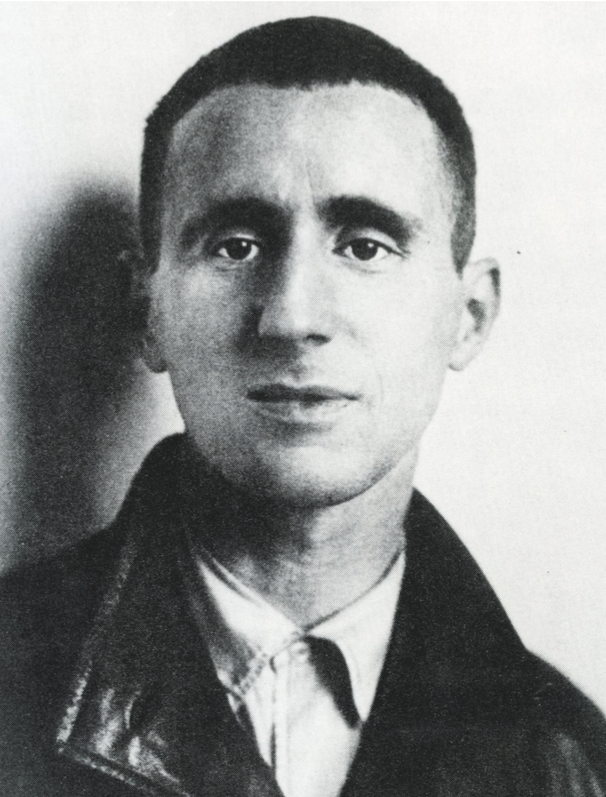

In Denmark during the middle years of the Second World War, radical lyric poet and playwright, Bertolt Brecht, included the lines above as an epigraph to the collection of verses named for his place of exile. Known now as a celebrated dissident and prominent émigré writer of exilliteratur, Brecht had fled the Nazi seizure of Germany and its accompanying crackdown of insubordinate artists and authors following the expurgation of his screenplay for Kuhle Wampe or Who Owns the World?, and just one day after the Reichstag fire. Brecht’s displacement later brought him to the United States, where he was subsequently blacklisted and forced to testify before the HUAC.

Bertolt Brecht, circa 1920

McCarthyism, Nazis, exile…you may be wondering why I’m digging up these dated demons of fascism. At the risk of anachronistically writing our doomsday politics into works of another era (or to the ArtNet-identified “disorienting Trump-is-everywhere effect”), I want to walk through Brecht’s “Motto” to discover a definition of our present dark times, field a query of our crisis in creating, and affirm art’s place as an upholder of radical imagination and resistance—for both the artist-denizen and the curator.

Truly, we live in dismal times. For many of us (including myself), the ability to think of this political era as a new or emerging menace is reflective of our multifaceted privileges. At the time of writing, no less than a dozen executive orders—in only twice as many days—have made real the threats many feared regarding the prioritization of white supremacist, capitalist, patriarchal interests in our executive office. Criminalized refuge, religious discrimination, repealed reproductive freedoms, and disregard for native land rights (just to name a few) are shaping the experiences that American artists both live and reference.

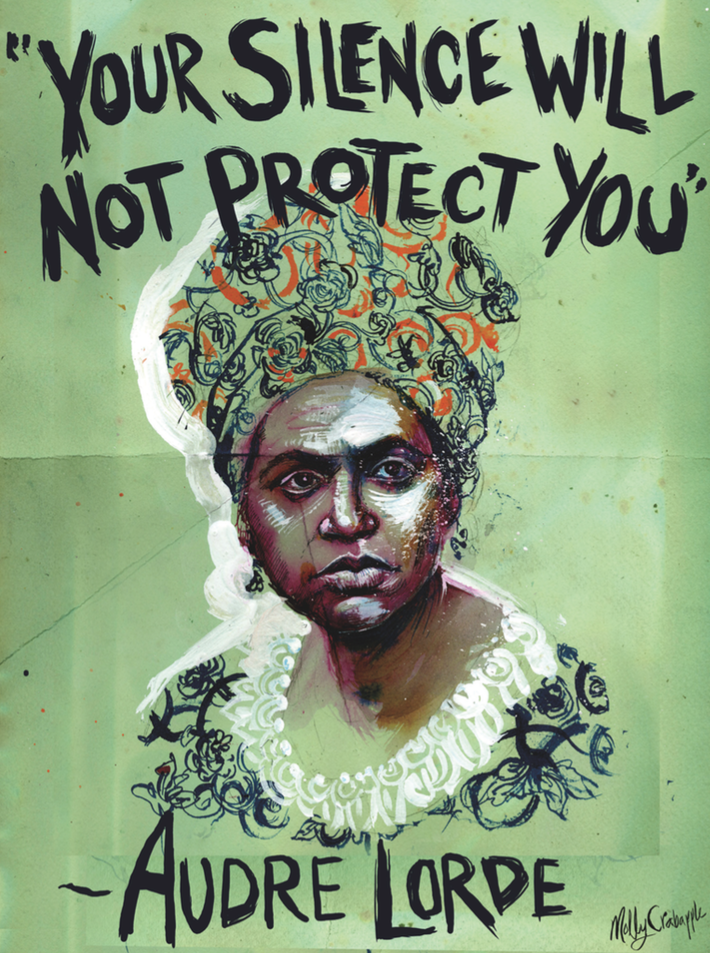

Threats to the safety and security—not to speak of prosperity—of ourselves, our families, friends, and neighbors are enormous, and we would be wise not to ignore what is at risk in the realm of the arts, which—formalists may disagree—is inalienable from society. Annual federal arts funding has never recovered from the post-Piss Christ cuts, but preliminary proposals from the White House’s budget office outline not only reductions in spending, but outright eliminations of cultural programs like pittance-recipients National Endowment for the Arts and National Endowment for the Humanities. Along with the hazard to education posed by a federal department that can’t spell DuBois, the recommended eradication of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting forebodes a dismal atmosphere for accessible creative learning. This conservative fiscal ideology signals the coming of an anti-art era, and raises the question, “Will there also be singing?” Or, can art endure and persist?

In times of fear and uncertainty—and totalitarianism—power is historically consolidated not only through policy but also through reasonable and necessary refocusing on so-called lower order needs by those under siege. In spite of this, a key aim for artists and viewers will be to resist the ideology of art’s irrelevance. Without denying the need for real and immediate harm reduction, or the critical questions surrounding the role of the artist as ally, I contest the view that art making and political action exist in isolated worlds. At its best, art is not an exclusivist escape but rather a mode of engaging with, understanding, and responding to the world.

Still, in mounting resistance, it is crucial to think deeply about complicity and allyship. To my mind, the most important action for artists and organizers in making and showing socially engaged, movement, or activist art is to make way for the work. Not only individuals, but also institutions and organizations, should be reflecting on reparations and employing power to refocus attention on work by those most specifically and urgently affected. More than ever, it is important to give credit where credit is due, to share resources, and to expand our proficiency in hearing and responding to criticism. For art institutions and curators, this is accompanied by the necessity to be courageous in selecting work that challenges, not upholds, dominance, and to reject exploitative arts.

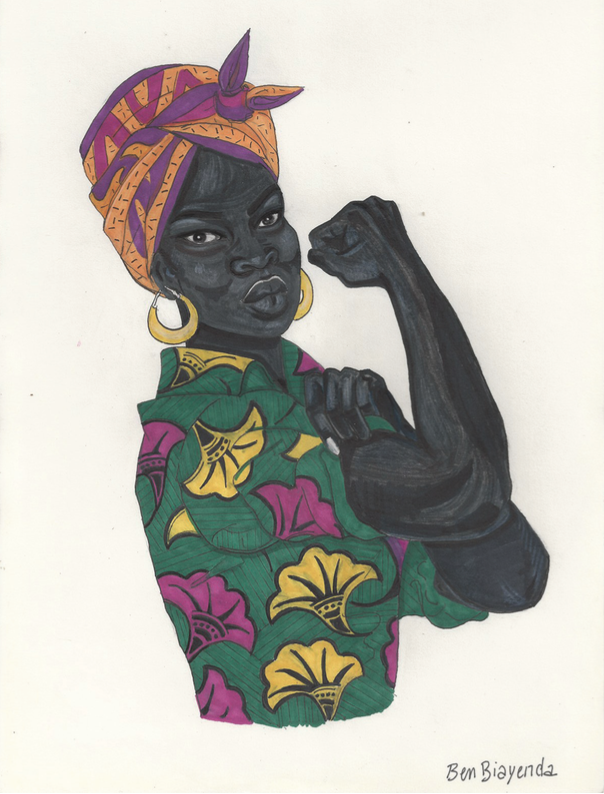

Figure Feminisme Noire, Benjamin Biayenda

To use a popular example, Shepard Fairey’s We the People series, and in particular his American flag hijab design, epitomizes solidarity gone wrong. In appropriating symbols and images, Fairey takes away attention and opportunities for artists of the identities he portrays to speak for themselves and to declare their own principles and priorities. This problem of erasure is disturbingly common. To serve as the cover image accompanying a recent Women’s March on Washington story, The New Yorker arts editor selected work by a white artist who recast the Rosie the Riveter archetype as a woman of color. This concept has radical potential but collapses under questions of why, if the intended message concerns intersectionally centering the struggle, creative work by someone closer to the intersections was not selected for publication. Putting her practice above subject matter, the cover artist responded to criticism of the magazine’s choice by suggesting, “You can read more about my entire, lengthy thought process behind the piece if you Google my name.” Instead, I searched online for Namibian illustrator Benjamin Biayenda’s Figure Feminisme Noire.

Right about now, many of us are clamoring to confront the mounting hegemony obscured by media confusion and policymaking by predator swamping. As we’re incrementally muted by the “banality of evil,” it’s important to refresh a recognition of a critical function of the work of artists—one that is connected to political power: artists make poetry agent through overwhelming obstacles. They provide both means of fathoming adversity and rendering interventions, counternarratives, and alternative inroads to grappling with it. Through radical imagination, they shape scaffolding for direct action—and even for singing—in and about the dark times.

You can see more at: AgenciesOrlando.Tumblr.com