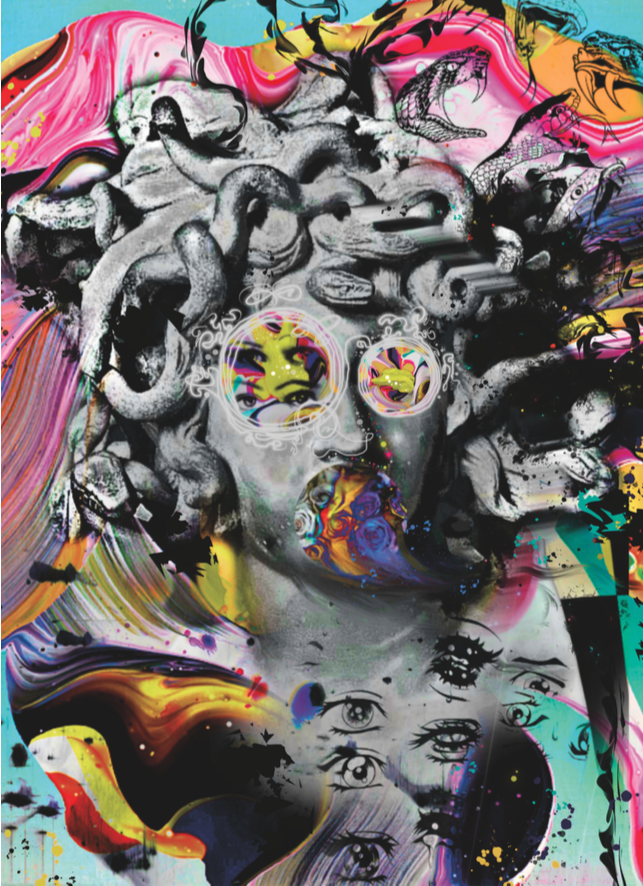

Le Surrealiste’, mixed media on canvas print

Nicholas Lucius is art. When “living halfway between reality and fantasy” is your modus operandi, creativity is a way of life and art is an absolute. Can a person ever find that elusive balance between reality and fantasy? Nicholas Lucius has not only found balance, but has a dual residence. Through his artwork, Lucius suggests that finding balance requires one to always have a foot in each of those worlds. Straddling the chasm between reality and fantasy might be difficult and uncomfortable, but having to choose between the two would mean death. At the very least, it would result in banality, which, for artists and creatives, is simply death’s synonym.

The artwork of Lucius is that rare bridge, or better yet, conduit between those two powerful worlds. In his work, the real and the fantastic collide, blend, and morph into something new. It is almost scientific. It is, without doubt, otherworldly. His effortless harmonization of two seemingly disparate worlds welcomes the viewer into this new space, a space he calls “a limbo between surrealism and pop.”

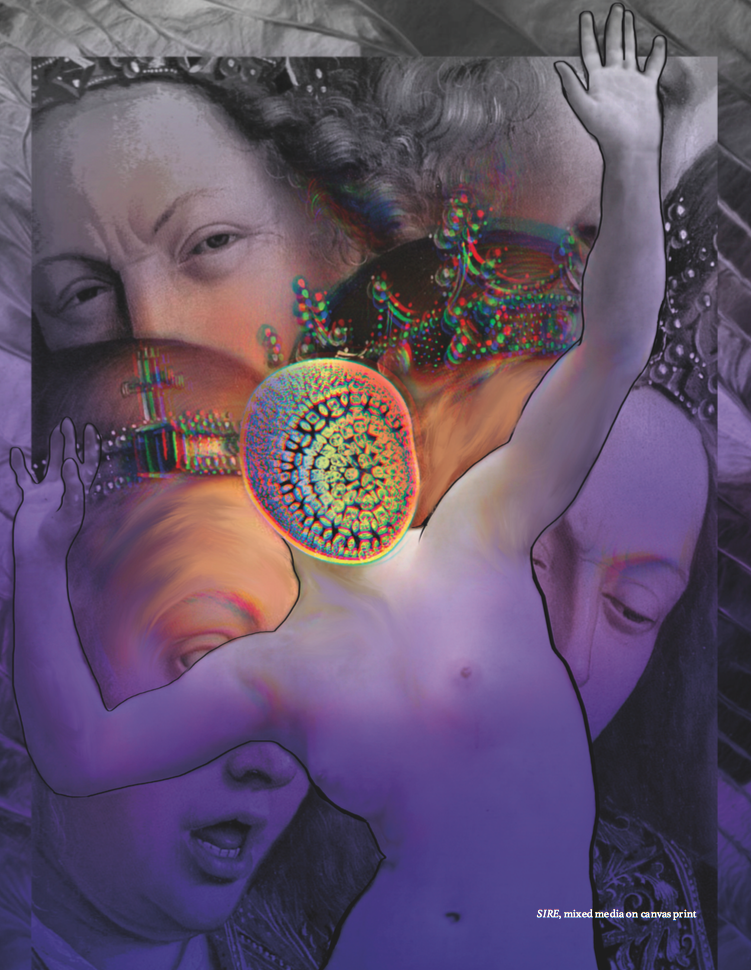

Reality Seize Me, mixed media on canvas print

Salvador Dalí and Andy Warhol are obviously his muses. He is the self-proclaimed “love child” of the two. With progenitors like Dalí and Warhol, one can never really feel at home living solely in reality or in fantasy. Having Lady Gaga—the pop world’s most creative multi-hyphenate—as your patron saint only reinforces that fact. Each world is too limiting. Yes, even a purely fantastic world can be too restrictive for an artist because it limits the artist’s audience. Lucius’ audience is all of humanity. It is in that mysterious unknown—the chasm where the two worlds meet, that new space—where the work happens. The human becomes the divine. The creation becomes the creator. Lucius is fully aware of this profound transformation and all that it requires. Of this personal and creative “reinvention,” he says, “I had to accept that as a lifestyle and not just call myself an artist. I wanted to be one.”

Pouring his being, passion, and personal truth into each piece, Lucius creates artwork that combines art historical references (the real world) with colors and imagery seen only on the best acid trips (the fantasy world). The collage technique is used brilliantly as images from antiquity, vibrant colors, and kaleidoscopic patterns overlap and bleed into each other. There are layers; so many complex and surprising layers.

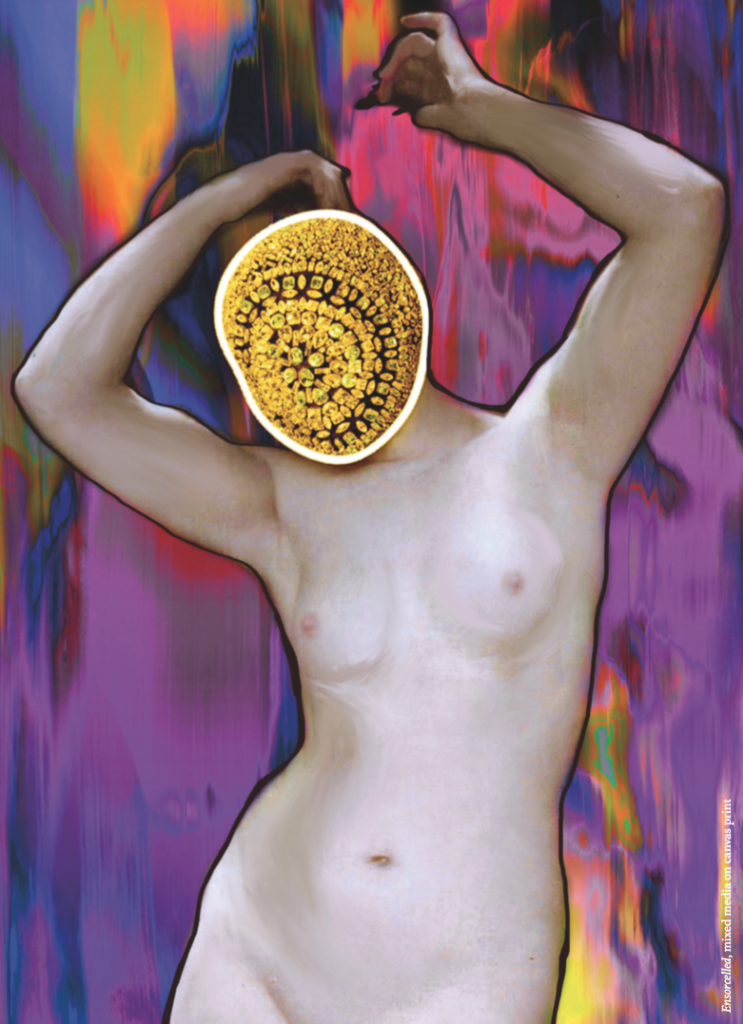

Fantasy Free Me, mixed media on canvas print

In his piece from 2014, Greetings Himeros, Lucius focuses on two sculptural heads from antiquity. In Phantasmagorgon, a piece from the same year, the subject is the sculptural head of the ancient, mythological creature, Gorgon. One look at 2014’s Tempt Me to Madness and your average art historian (like the humble writer of this piece) sees a reference to Matisse’s Dance in the movement of the figures’ bodies. These art historical references ground the viewer in the real world. They are the “known unknowns”—things that everyday, ordinary people recognize even if they cannot identify their provenance. The Gorgon’s head might have been a memory from an old text book on a chapter that discussed Greek mythology. Matisse’s painting of Dance may have been on a notecard from a friend who wanted to reconnect after years apart.

Phantasimgorgon, mixed media on canvas print

Including art historical references that are superficially recognizable, but require no further inquiry to appreciate them, is the key. In the piece Phantasmagorgon, the viewers need only recognize that the focus of the artwork is the head of Medusa. The artist who carved the sculpture, the date it was created, and its current location in the world is unimportant. Lucius makes the initial connection with the viewer by finding commonality with him or her in the real world. It is in this moment of comfortable recognition that the fantasy world collides with reality. It is too late to turn back and the viewer is right where Lucius intended. In Phantasmagorgon, rivers of color flow in and out of the Gorgon’s head. Upon closer inspection, the viewer sees hand-drawn eyes and snakes surrounding the figure. There is so much to look at in this one piece that the viewer’s eye cannot rest on one thing. It is like Lucius is reaching through the piece, grabbing the viewer by the eyes and pulling them into the artwork. The viewer is no longer a passive participant. Through his work, the viewer gets to experience the same chasm between two worlds in which Lucius resides.

Explicitly Beautiful

Nicholas Lucius is evolving. This evolution is exponential. In just two short years, there has been a distinct and obvious difference between pieces from his new series, Explicit Beauty, and pieces from 2014. The art historical references are there. The colors akin to a “hallucinatory rush of adrenaline” are there. Yet, something is different. Before labeling those differences “maturity,” one must look closer.

In the 2016 piece, Bleached Beautiful, Lucius forces the viewer to focus on the figure and only the figure. Drawing from his art historical arsenal, he utilizes a “classical female nude”—probably one the viewer has seen a hundred times over in places already forgotten. She sits on a technicolor cloth against a background of erratic shading. She is recognizable yet nameless at the same time. With her face obscured by a patterned object, a motif seen repeatedly in Lucius’ new work, the viewer must acquiesce that she cannot be identified.

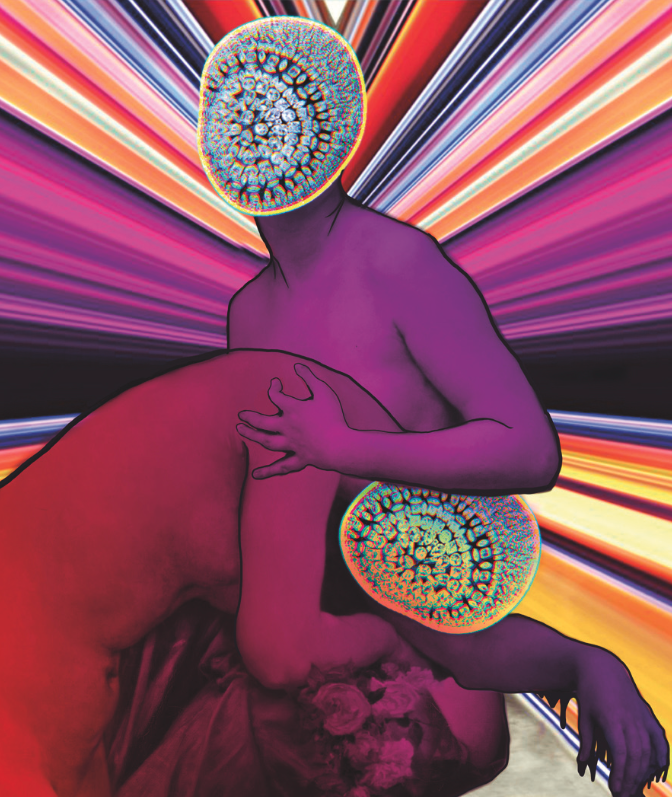

In a New Direction, mixed media on canvas print

This unidentifiable woman is just out of reach. She is familiar, but also distant. The viewer is drawn to her, but the reasons for this gravitational pull are seemingly unknown. Is it her physical beauty? Is it the alluring fascination with the unknown? She is all of this and more.

Aptly titled Explicit Beauty, Lucius’ new series invites the viewer on the same journey he is taking as an artist and as a human being. He is exploring feminine divinity and all the mystery and bewilderment that goes along with it. Lucius encourages the viewer to connect with the female figure on another level, a level far beyond that of sexual objectification. He is once again straddling the divide between two worlds and, in his new work, the worlds are the secular and the divine.

Nicholas Lucius is enlightened. Drawing from his own personal exploration of human sexuality, he is shifting his own perspective and thereby shifting the viewer’s perspective. Early works spoke to his fascination with the male form. Pieces like Tempt me to Madness and artPOPIST have a distinctly voyeuristic approach. There is, at first, curiosity, then participation, followed by ecstatic celebration. It is the joy that comes with the “a-ha moment’ of complete and total self-awareness. Of this time in his life, Lucius recounts, “For the first time, I felt like I found my voice.”

artPOPIST, mixed media on canvas print

If Lucius’ early work is the loud, raucous exploration of human sexuality, the Explicit Beauty series is his investigation of humanity’s solemn fascination with the sacred. The “classical male nude” has been replaced by the “classical female nude.” The colors and patterns that once seemed to define each piece now tend to recede into the background so that the figure can take precedence. Indeed, the layers, previously used so expertly to express fantastic chaos, no longer scream “collage.” The layers do not scream at all anymore. Instead, the layers are more understated and seem to sing. They sing the praise of the feminine divine. The Explicit Beauty series exchanges voyeurism for meditation, and flesh for spirit. Lucius trades sexual ecstasy for emotional ecstasy and the result is universal and profound: one cannot exist without the other. This new series explodes with life because of the work that came before it.

By removing the sexuality of the female figure, Lucius puts the viewer in the same position as the artist himself. He explains that he is “experiencing her [the female figure] through the lens of the 11-year-old boy who couldn’t really figure out why he never found her [sexually] appealing.” Instead, he is “identifying with her in emotional and creative ways.” With the elimination of physical sexual attraction, Lucius and the viewer are forced to connect with the female figure in some other way. He has effectively elevated the “classical female nude” to icon status. Much like the Virgin Mary in Christian mythology, the female figure is humankind’s doorway to that which is holy.

Does Lucius’ new work supersede his past work? Not in the slightest. If anything, his Explicit Beauty series complements and enhances his existing body of work. It reiterates the need, not only for Lucius, but also for humanity itself, to live with one foot in each world, however one chooses to describe those worlds: the masculine and the feminine; the sexual and the spiritual; the secular and the divine; the real and the fantastic.

Nicholas Lucius is art. He is channeling both the real and the fantastic and the work he creates is the result of harmony between the two. Through his artwork, Lucius illustrates how chaos and order can dwell within the same being. They are inseparable and complementary. He is perfectly at home in that chasm, that new space between worlds.

Brand New Persons, mixed media on canvas print

You can see more at: Thaumaturgical.weebly.com