When we think of untold stories in art, we think of putting a voice, a past, a face to ordinary people. Launched at Maitland Art Center’s Culture Pop event, Untold Stories features two exhibitions that chronicle personal and cultural narratives within a wide historical context.

Long view of the hall containing Inspired Storytelling: Tomengo’s Maitland Project, photo by Mariana Mora

In Inspired Storytelling: Tomengo’s Maitland Project, Trent Tomengo’s series of oil paintings are based on photographs and artifacts of Maitland’s working class residents from the turn of the century. Tomengo’s works are anchored in Maitland and its surrounding communities, but they are used to represent a larger working class that built the U.S. at the height of the Industrial Age and beyond.

The first thing you encounter in the exhibition is a glass case of artifacts: an antique drill, a clothes iron, a small basket, and a photograph accompanied by four standard 8″x10″ portraits of George Horatio Packwood, Clara Dommerich, Isaac Vanderpool and Sarah Waterhouse. Along with the portrait of Jules André Smith, founder of the Maitland Art Center, they are used to recognize Maitland’s well-known historical figures.

Tomengo’s striking portrait of Swedish-born pioneer Josef Henschen is given a lively makeover in bright, circular pops of color. One of the three major investors in the Orange Belt Railway, Henschen played a key role in Swedish migration to the United States, employing immigrants in Sanford and giving way to their settlement in Maitland. Along with his portrait of Joseph Clark, founder of Eatonville, Tomengo pays his respect to the overlooked men of Maitland. Clark is shown facing the sun; the mixture of yellows in his hat and the background of the painting are a reference to his pineapple field. The sky is light, clear, serene, and calm—a perfect compliment to a stoic Clark.

On opening night, Tomengo mentioned the African American experience as one ridden with images of strife. Through Alligator Man, he captures the liveliness of an African American railroad laborer whose life is more than the toils of work and discrimination. The image is based on a photograph from a book on the history of Maitland, showing an African American man holding an alligator. Small, glittering circles form around him, reflecting the lighthearted day-to-day moments of the working class. His overalls are barely recognized as rings of violet and gold encompass him.

By the end of the second gallery, viewers find three iconographic portraits titled Swedish Carpenter, Housekeeper, and Dressmaker. Using an arched, Gothic stained glass window motif, the three “saints” are venerated for their contributions to the local community—as “ordinary” as they were. Tomengo painted them in their modern manifestations; the carpenter wears blue denim and a white t-shirt; the housekeeper, a modest uniform; and the dressmaker, a pink dress with a casual blue jacket.

Not all of Tomengo’s pieces are portraits, but they are indicative of a community’s rhythmic transformation. The three abstract paintings, Change, Interstate 4, and TRANSITion represent the past, present, and future of Maitland, respectively.

In Change, Tomengo interprets the Great Freeze of 1894-1895 that destroyed much of Central Florida’s citrus crop as a cyclical, necessary process. The freeze gave way to a homesteading trend in Maitland that revitalized the local agricultural community. The vivid, chrome orange and blue capsules embody the citrus crop and the frost that killed it, in a pentagon frame. The Yin and Yang symbol that encircles Change suggests that the blue frost and orange crop compliment each other in a contrary, yet interconnected relationship.

Maitland Art and History Culture Pop, photo by Roberto Gonzalez

The anxiety felt by members of the Eatonville community during the establishment of I-4 is immortalized in Interstate 4. The parallel moving arrows and trail of pearlescent bubbles are broken up with a few, thin, black lines dispersed throughout the piece. They look like slight cracks in the highway’s foundation, indicating fractures in the Eatonville community after the highway’s inception. Given the context of the piece amidst the highway’s renovation—officially titled the “Ultimate Improvement Project”—Interstate 4 gives an almost ominous, jarring warning of how detrimental progress can be to certain communities.

TRANSITion moves this idea forward with the development of the SunRail station in Maitland. Pipeline tunnels of electric blue and orange cover the mustard yellow background map. The painting isn’t nearly as chaotic as Interstate 4, indicating the commuter rail system as a positive contribution to Maitland’s economy.

Tomengo’s art prompts viewers to dig deeper into the histories of the people and events portrayed. The richness of his works may go underappreciated by those eager solely for surface-level, historical homage. Look a little closer and you’ll find a thoughtful, egalitarian perspective on what it truly means to be working class. The Maitland Project shows us who we were, where we are now, and what we can be.

Similarly, The African American Narrative, a showcase of contemporary African American artists on loan from the Polk Museum of Art in Lakeland, navigates the past through the present. The show features works from Faith Ringgold, Radcliffe Bailey, Howardena Pindell, and Lorna Simpson. They take on both personal and universal themes of race by mnemonically marking their works.

Radcliffe Bailey’s focus on ancestral history in contemporary society permeates through his work. In Between Two Worlds, a sepia toned photograph of one of Bailey’s ancestors is surrounded by contour drawings of boats with hues of red and green with a hint of yellow–all colors associated with Africa. Bailey’s use of found material and strata of mixed media highlight the layers of meaning in Between Two Worlds. The scraps of velvet alone create a frame for the photograph and emphasize the faint, cerulean streaks and dark green scratches (representing trees and roots) layered underneath, suspending his subject quite literally between two worlds.

Maitland Art and History Culture Pop, photo by Roberto Gonzalez

Also using texture, color, and layering to create a thread between past and present, Howardena Pindell’s Kite Series: Norway has a slightly darker take on race and memory. At first glance, her paper collage kite looks like an innocent memento of childhood gaiety, but the array of mostly red, multicolored dots that frantically cover the kite echo segregated practices. In her statement on the piece, Pindell recalls being given a mug with a red circle underneath it at a root beer stand when she was a child, indicating that a person of color was to use it. Pindell’s spin on the red circle is a conscious effort to reimagine it as a positive, rather than unsettling, fixation.

Faith Ringgold’s color lithograph, Sunflower Quilting Bee at Arles features eight iconic African American women–including Madam Walker, Harriet Tubman, and Rosa Parks–holding a “story quilt” covered in sunflowers. The scene looks as if the group united in Arles, smack dab in the center of a Vincent van Gogh painting; van Gogh himself looks on curiously in the upper right corner of the piece.

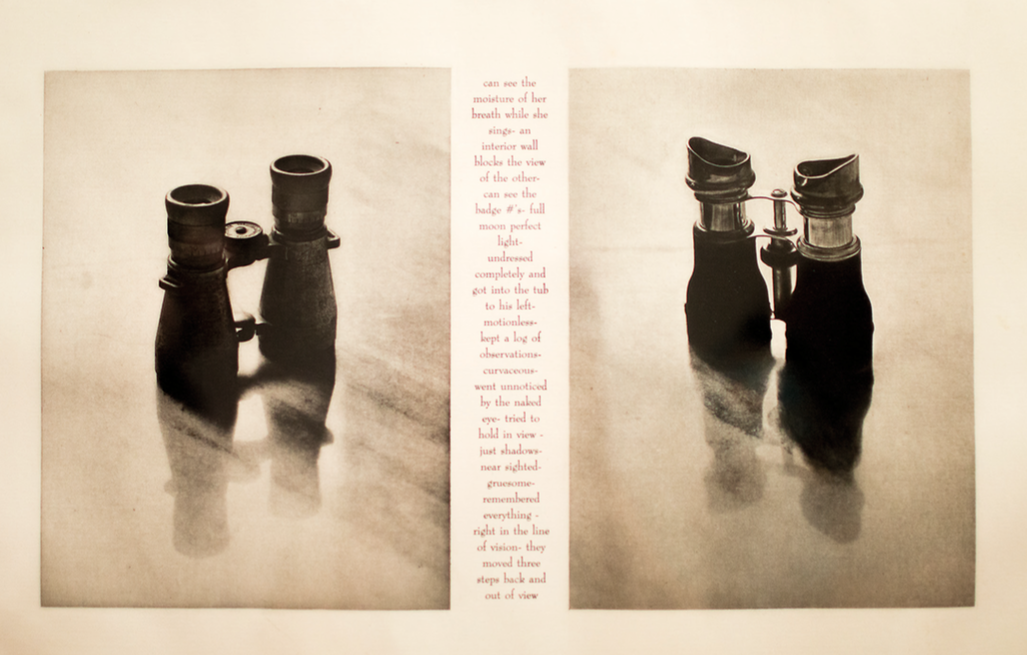

Detail of Lorna Simpson’s Two Pairs (Binoculars), photo by Mariana Mora

The same sense of voyeurism is found in Lorna Simpson’s Two Pairs (Binoculars), where a barrier of text containing fragments of observations breaks up Simpson’s two photographs of binoculars. Two Pairs is, itself, a fragment of the artist’s fascination with the idea of imagining and observing various scenarios.

Maitland Art and History Culture Pop, photo by Roberto Gonzalez

As an added bonus to the exhibitions, a station is set up with an interactive typewriter activity so that we, too, are prompted to record and revisit our own untold stories.

Untold Stories will be on display at the Maitland Art Center until September 4, 2016.