Gary Bolding’s latest collection of work, on display at Stetson University’s Hand Art Center, focuses on a small oil town in southern Arkansas known as Vaselina Springs. Home of 25,104 individuals, including the Blackfish family, members of the Choctaw tribe, and the infamous Lester Harley, founder of Athena Oil. If you haven’t heard of Vaselina Springs, you are not alone. Bolding has spent years creating this town and documenting it in great detail. From maps to timelines that start with the Garden of Eden, there is little Bolding doesn’t know about this town. It is hard not to get wrapped up in this fantastic place that he illustrates through paintings, short stories, letters, and songs. This ongoing, collaborative body of work evokes a sense of Americana while preserving the disappearing southern oil towns.

Jenn Allen: How do you pronounce Vaselina Springs?

Gary Bolding: Vay-sah-LEE-nah Springs. That’s specifically because the town I grew up in is technically El Dorado (doe-rah-doe), Arkansas, but they pronounce it “doe-RAY-DOE.” I always say I grew up in a town that didn’t know how to pronounce its name.

How long have you guys been working on this project?

This is all about this imaginary town called Vaselina Springs, in South Arkansas. The whole thing is a soap opera; it’s a serial. It comes in installments—it might be a painting, it might be a song, it might be a drawing, it might be a short story. Part of this project is what’s called epistolary fiction, which is fiction in the form of a letter. It actually started out as some story songs. It’s something I always did for fun. When I wrote the first three songs, I had no idea that it was going to grow into anything. They were written in the ’90s. At some point, I realized that these story songs were about three generations of women in the same family. One was about an older woman, and two were about younger women in different historical times. I realized that they were all related, and then it just kind of went from there. I started writing songs to fill in the gaps of the narrative, so that you had a chance to understand that these people are connected.

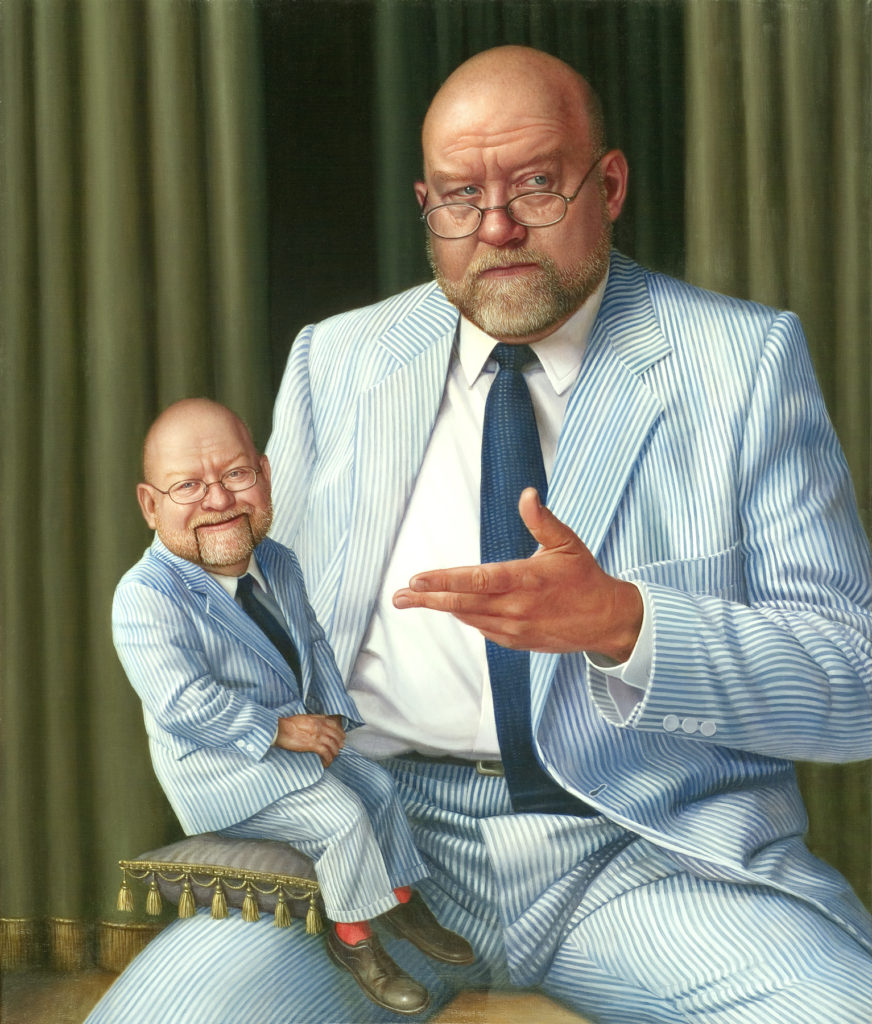

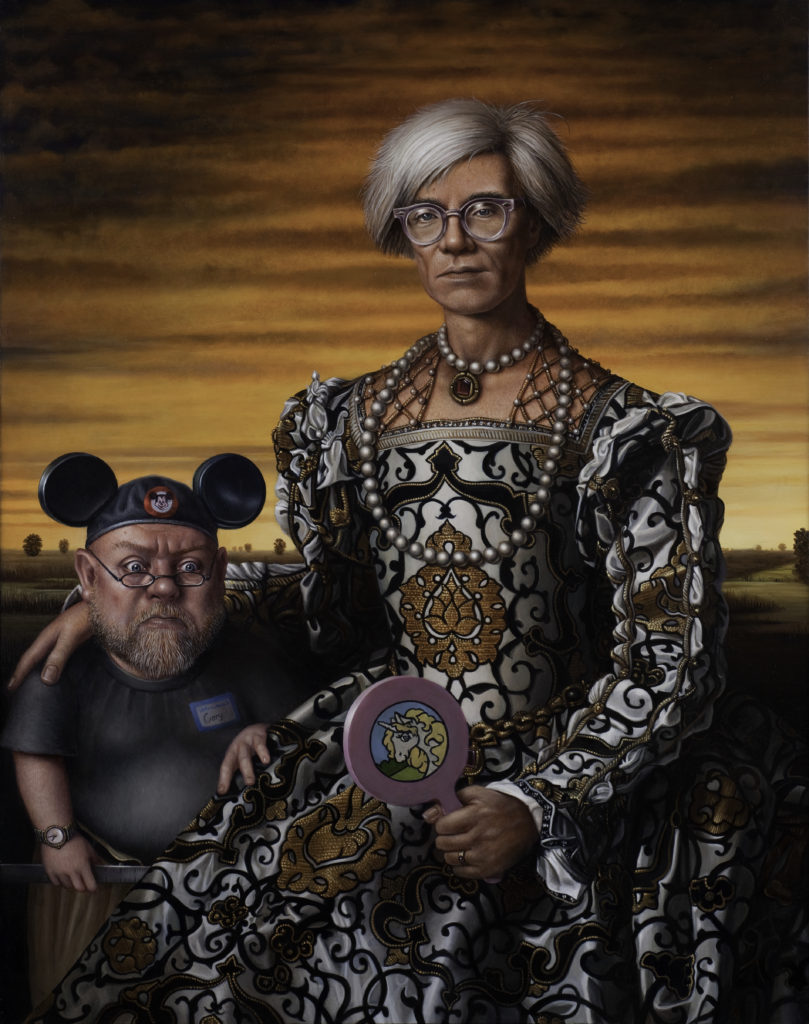

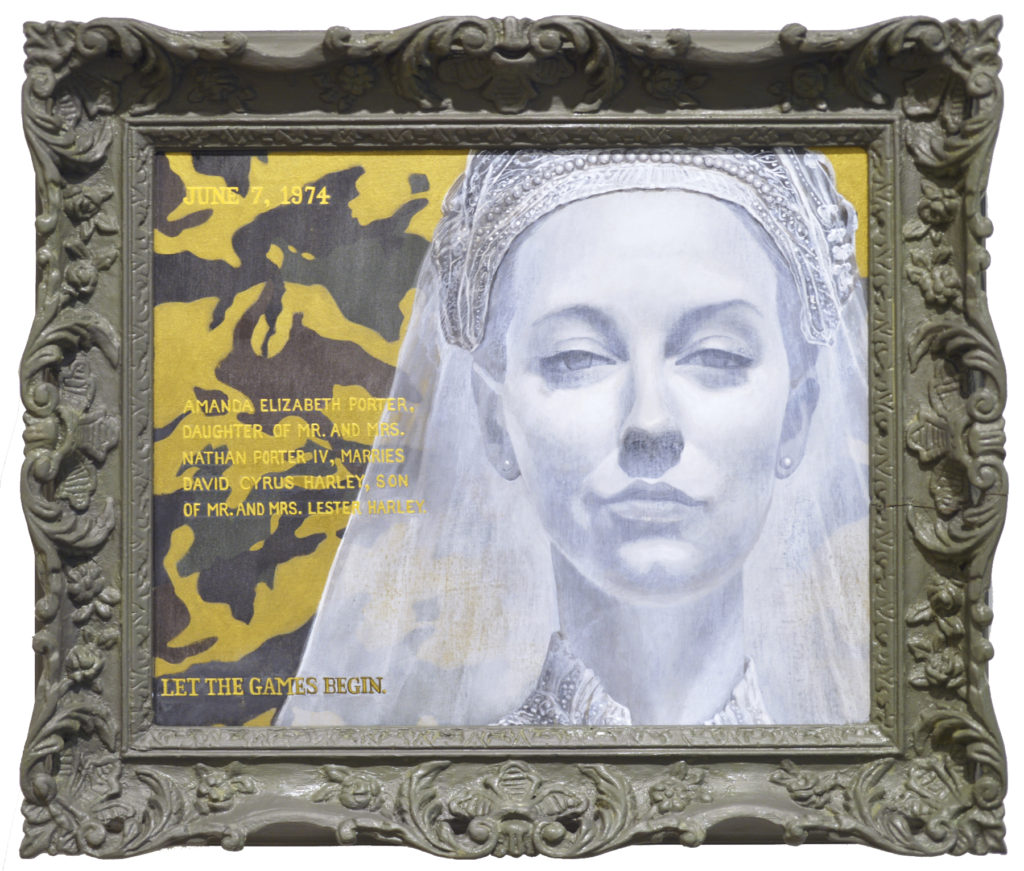

The pieces that are in the show at Stetson are more illustrative of what is going on in the actual song. It is more of an instillation piece. Each song has several images that are picked out and painted. They are painted on camouflage material and they have these really elaborate frames. I have about 40 songs, or so, right now, and each CD would have an installation piece of images that accompany the audio. For each CD, I make a little painting of a character so that each CD has gone through my hands and has a different person who lives in the town. Some of these people could become part of the narrative. As long as the CDs are moving out, I will continue to make more portraits. The population isn’t necessarily all present day. The story starts in the Garden of Eden. Some of the 25,104 citizens might be from the early 21st century; some of them might be from today. Some of them are ghostly and from the past. It’s a multi-generational story. Now, I have so many characters, and I start to see a resemblance in them and create families. In the Harley family, Lester Harley started this company, Athena Oil; Athena, always the wise choice. Athena was the goddess of wisdom.

Are all the faces in the CDs made from your thumbprint?

They almost all start as thumbprints. It’s amazing how the thumbprint starts to suggest a different face, or a different gender. I don’t have any preconception, I just put my fingerprint on and then if it doesn’t look like someone, I’ll put another fingerprint on top and, pretty soon, little eyes and noses—it’s just one of those natural things.

Do you create these characters first and then find the models?

Yes. Some of them are hard to find. For Lester Harley’s son—who is kind of a bad guy—I was originally using Alec Baldwin as a stand-in, but I have to find somebody that is an Alec Baldwin type without being Alec Baldwin. Because this town population is 25,104, all the characters live together, and because it’s an oil town, they’re all really wealthy. The first part of the timeline seems to dwell more on middle class/working class redneck kind of people, but it’s very much about class and the American class system. And it’s also about race. It is talking about these things through specific stories of people who lived at this time. I hope that I am not preaching to the choir. What I am trying to do is show that it’s a grey world, it’s not a black and white world. Everybody has good and bad in them, so they’re not one-dimensional characters. People are complex. I am not trying to paint one group as all being the heroes and one group as being all evil. It’s more complicated than that.

Why did you feel that it was important to have a musical component with your paintings?

It’s not so much that I think it’s important, it’s just something that delivered itself. All this stuff just kind of shows up and wants to be created for whatever reason. A friend of mine who used to own a recording studio came down for a visit and we were playing a little gig at one of the bars downtown. We were playing some of the original songs and he said, “You should come up and record some of these.” So we did, and that was the start of it. That was a number of years ago. He just started asking me questions about the songs, so I started writing songs, and making up stories that filled in the gaps. While I was writing about what was happening, the writing started to become art instead of just explanation. Because I’m a painter, I started making images that are illustrative of the place itself.

I am starting to work with a guy in Arkansas who is a filmmaker, so we’re going to add some video components. He’s got all these ideas on how you can make an installation piece where there’s video on all four walls, the ceiling, and the floor. People will be literally walking into the images. It is a reaction to the sensory overload in cinema. You have images, and story, and the overwhelming visual experience of being in a dark room with this brightly colored picture that is 30 feet high, and then sound on top of that. In a way, it is influenced by this operatic approach by bringing a lot of art forms into the picture. A lot of that is because people seem to require a lot of stimulation now. In order to get someone’s attention, you have to do a lot.

You tend to use a muted and cold color palette, which is an interesting contrast to the bright colors of the sensory-overloaded cinema.

I made the decision to use a limited palette. These colors are so dull, that the color that functions as a red is actually a brown. The name of the color is Caput Mortuum, which is “dead head” in Latin. A lot of the modern colors are synthetic, but these colors have an alchemical quality to them. Most of them have Latin names. They are these organic colors made out of dirt, which I like. It also allowed me to have a little bit of warm and cool. The limited palette emphasizes the suggestion of memory and time; a fleeting memory. This petrochemical world is disappearing, and it’s going to become like the ghost towns from out West. There is a bleakness about it, but I see a beauty in it, too. It’s a sad, wistful kind of beauty. For a lot of people, this is the world we have. You can see its fault, but also look for the beauty or aesthetic. There is a despairing quality, but there is also a sort of embrace of the beauty that is still there. Some parts of the paintings are more specific and some parts are indistinct, but because you see them in the context of the painting, it becomes a cohesive image. I like the effect that it seems dreamlike.

You’ve definitely captured that dreamlike aspect, and painting is such a nice medium to capture the feeling with. If you used synthetic colors, it wouldn’t come across as a memory, but as a more factual representation. Did you use the limited palette for that specific reason?

Yes, I wanted it to be more tonal, and more like a drawing. Some of my early inspirations for these paintings were the black and white, post-impressionist drawings by Seurat, which were done on textured paper. They’re just suggestions, nothing is hard-edged or spelled out. There are no lines. The tonal variations make up the image. When I first started the abstract paintings, I was working completely in black and white, stripping down to essentials. Part of the reason I work with the palette is to give myself limitations. It is also about creating the mood.

I think it’s interesting that you chose not to make your images black and white because that could have been an easy way to suggest time and memory.

It’s too obvious of a trick. But I also really love gray. This gray that I’m using, Payne’s Gray, when you use the cool gray next to a brownish gray, it looks blue. That’s the thing about color; it exists in relationship to other colors. You can make colors look really different depending on what you accompany it with. I like the idea of having something that looks like a dark, cool red, which actually is considered in the brown family. But you can make it look red if you use it in a certain way.

And using colors in your grays add dimension to your pieces. They are not flat at all. Sometimes with paintings, when they are more photorealistic, your attention is drawn to the surface, but your work feels like it is going back in space.

I’ve never considered myself a photorealistic painter. People have described my previous work as photorealistic, but almost all of them are done from life or imagination. There was no photography involved; it was done with a mirror. Sometimes I would use a model, but then make up the room. It was never about reproducing a photograph. I had been doing these very tight, realistic paintings—very labor-intensive and very smooth. After a point, I completely broke from that and started doing big abstract paintings. I used textures and different materials, different tools. With these paintings for Vaselina Springs, I’m taking the approach of the abstract paintings, but I am making images with that same technique. It’s all in the way that I’m handling the materials. There is a lot of putting on, scraping through, building up layers of textures. It is a step-by-step process. I excavate back through.

The project as a whole is still developing, and I’m collaborating with a number of people who are all helping me create this project. My assistant, Stephanie, is helping me do social media, which we are just getting started. Everything will be archived on the website. You will be able to read all the letters, see the images, which won’t be the same as seeing them in person. I have thousands of photographs. You will be able to see all the little portraits of the citizens and the music will be there. Right now, we are releasing one song a week. The website is such a nice virtual venue where people from anywhere can access it. The flip side of that is that we are going to do a live show at my home. Two of my friends from Arkansas are coming down, and two of my friends from here are going to play. It is like a roadside attraction to me. I have a stage outside that we will play on for a small audience.

Gary Bolding is a professor at Stetson University in DeLand, Florida

Collaborators for his project, Vaselina Springs, include:

Charlie Chalmers

John Davies

Stephanie D’Ercole

Matt Dickson

Rachel Fields

Andy Griebel

S. Herbert

Ed Nicholson

Will Nicholson

Tara Norwood

Darren Novotny

Barbara Raney

Jeff Woodward

Gary is holding an essay contest for tickets for the private concert at his house.

For more information, visit GaryBolding.com and VaselinaSprings.com