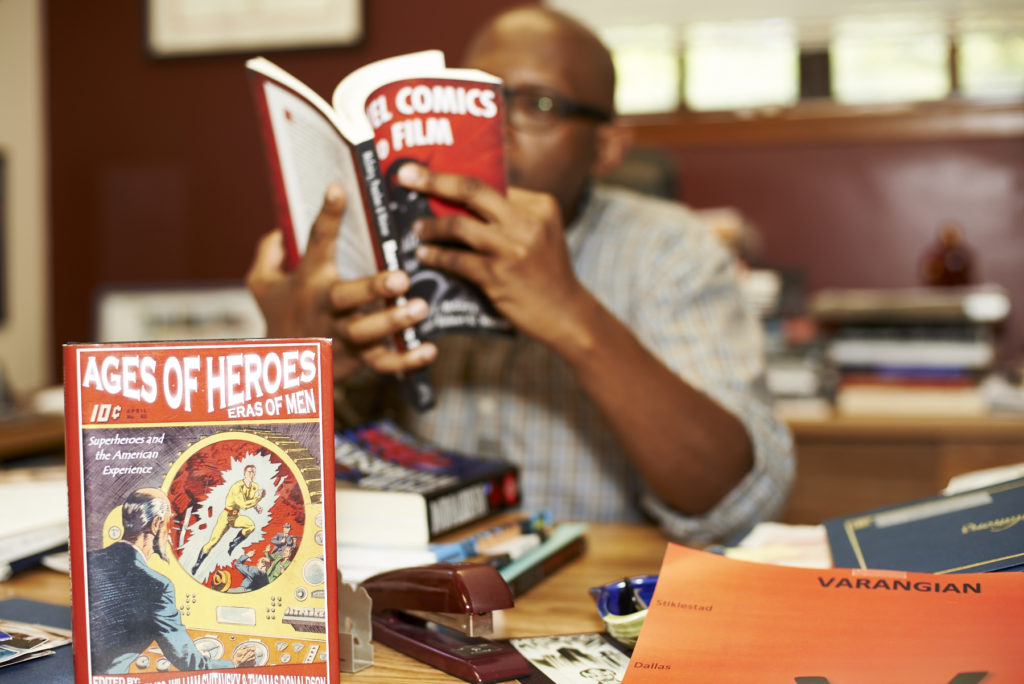

Dr. Julian Chambliss is a professor who is very good at what he does. And that is to profess. With little prodding he can lay a plethora of interesting, thought-provoking knowledge and opinions out for you. Dr. Chambliss serves as coordinator of the Africa and African-American Studies Program at Rollins, and Coordinator of the Media, Arts, and Culture Special Interest Section for the Florida Conference of Historians. After a short walk through the beautiful Rollins campus, our interview took place in his cozy office, overflowing with books, comics, and comic book memorabilia.

Julian Chambliss presenting “The History That You Feel“ at PechaKucha Nite Orlando v.18, photo by Davina Hovanec

One of Chambliss’ big claims to fame is his TED talk about how the story of superheroes in America reflects the story and the struggles involved with urbanization and the U.S. experience. Another accomplishment of Chambliss’ is one that might gain him fame, but in a more notorious sense. On Memorial Day 2015, he took part in a project organized by John Sims to bury the Confederate flag.

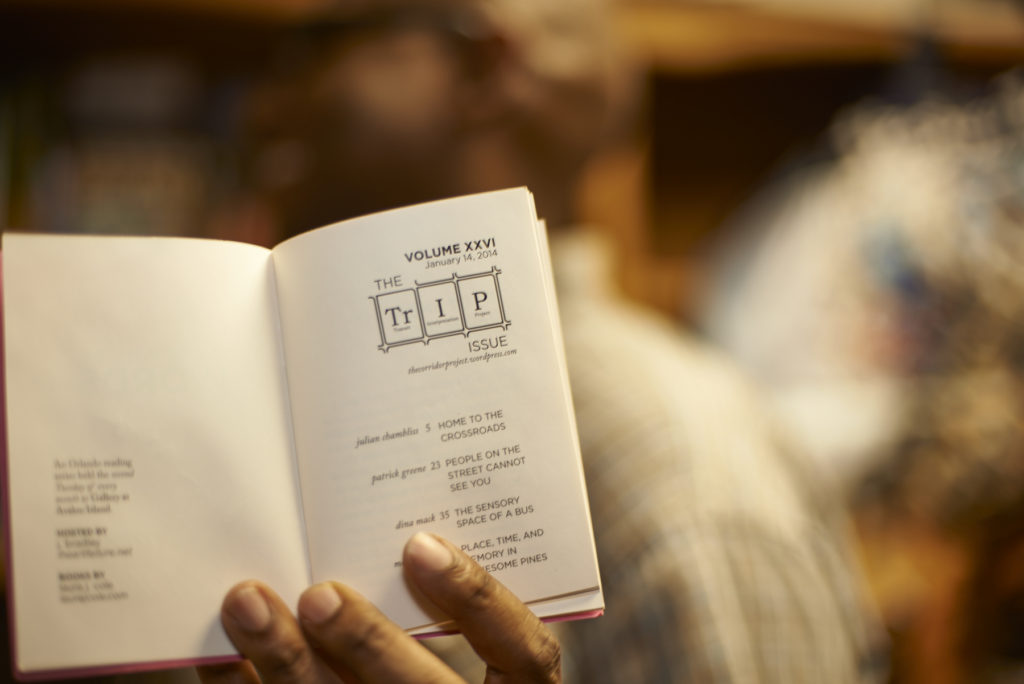

My personal interest in comic culture and the growth of our great city Orlando led me to consult with my good friend and comic expert, Nick Grondin, to think of some creative comic related questions to ask Chambliss. I was, and still am, interested to hear his perspectives about the way urban space shapes our communal interactions, and how comics interplay with culture. I was so caught up with that end of his story that I overlooked asking about the flag ceremony in our initial interview. So, this is a two-part interview. The first part is about academics, comics, and the Orlando art scene. The second part occurred after our original interview and outlines the funeral for the flag, the nature of the Confederate flag and how we deal with it as a modern society.

Rob Goldman: So, let me see, where should I start? In the past month, what has been your focus of study?

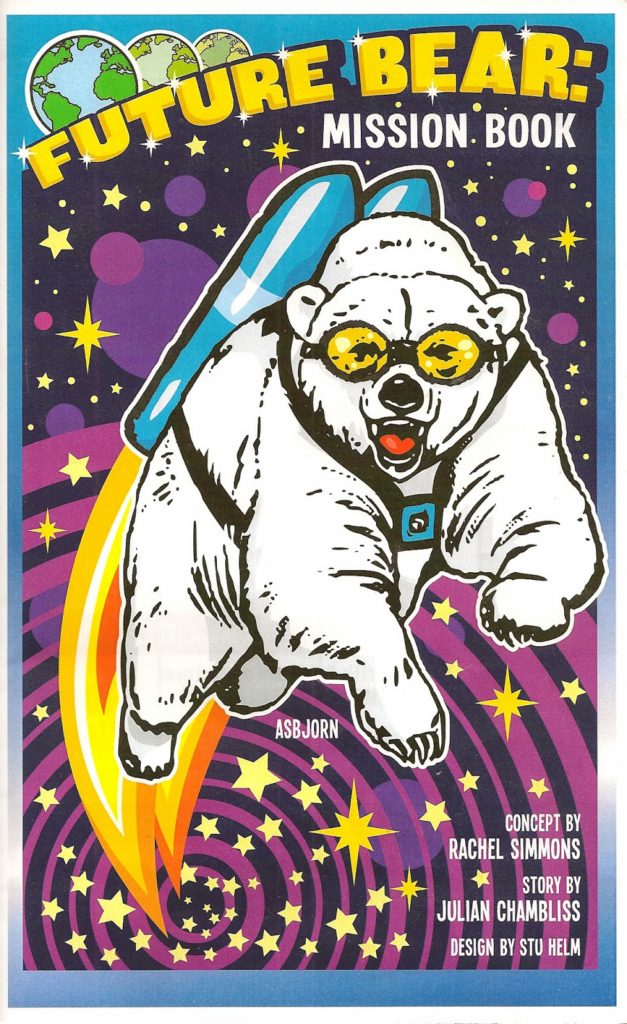

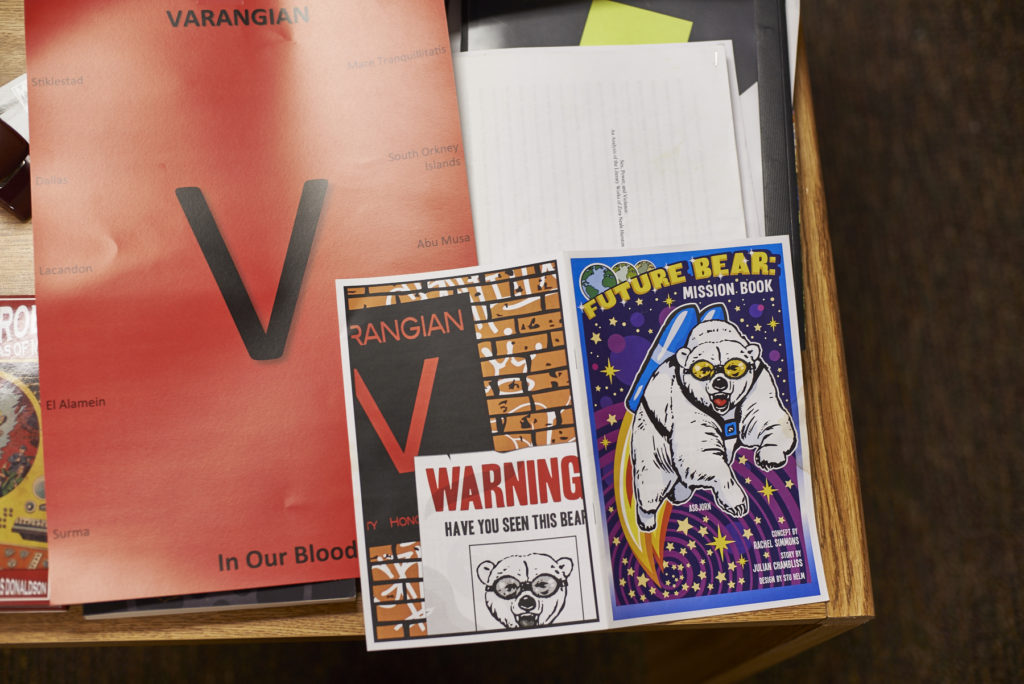

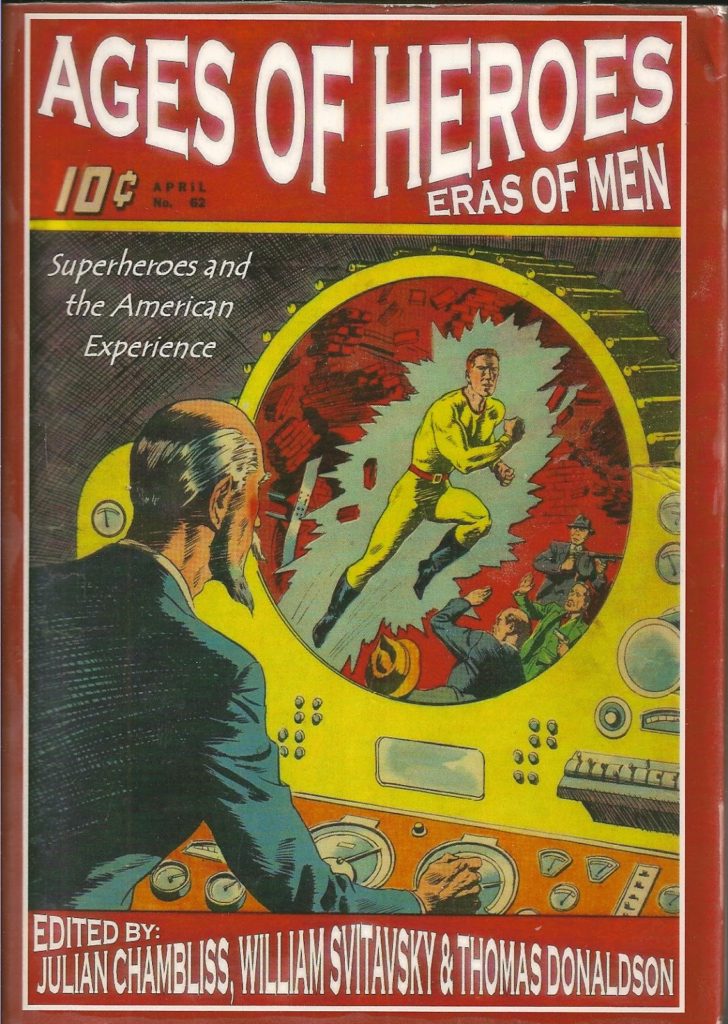

Julian Chambliss: In the past month, I’ve been really concerned with a couple things. One is a book about the Marvel cinematic universe I’m coordinating and writing for with some colleagues. It’s about superheroes that are in the movies produced by Marvel Studios. So, when I think about their comics, that’s the thing that sort of distinguished modern Silver Age comics from Golden Age comics. The idea that all these characters are sort of living in the same world was not actually introduced in the first comic book age. It develops over time. With that development you get an opportunity to tell these shared universe stories, which happens in comic books but not so much in other media. Marvel’s doing a good job. The book is about all that.

Other things I’m working on, of course, are a lot to do with preparing for class and thinking about the research end for that. I’m doing a class on Afrofuturism, which is called Afrofantastic. That is a new class for freshmen. We’re also going to curate a show in the Cornell Fine Arts Museum called Afrofantastic. So, I’ve been working on getting the objects together that are going to be part of that show, and sort of mapping out how the class will go.

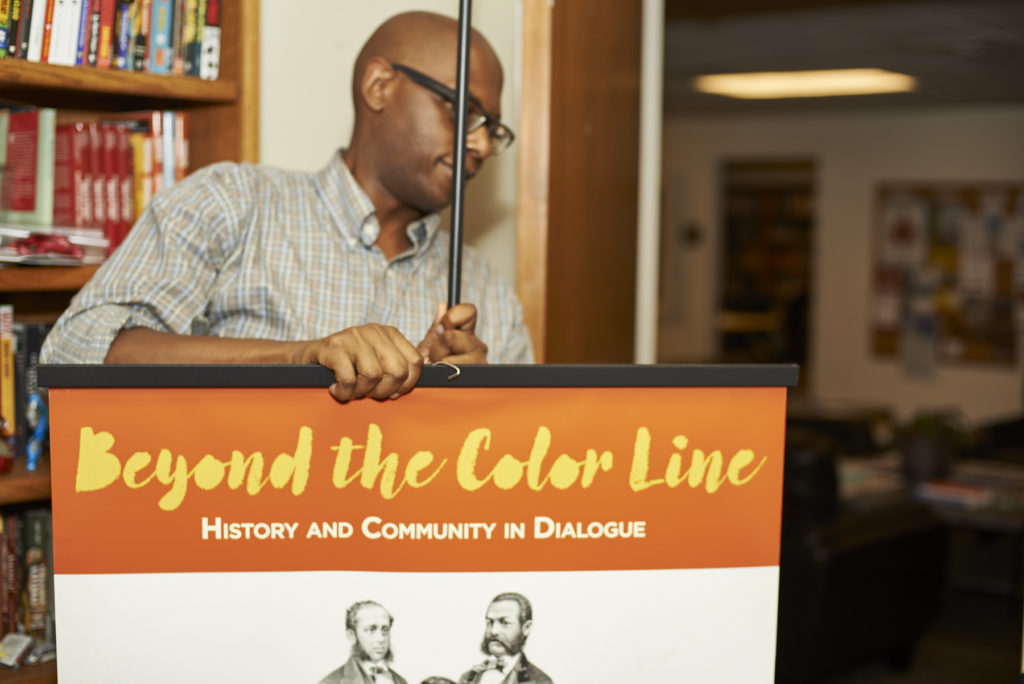

Introduction banner, by Dr. Chambliss, to a pop-up exhibit of Black history in Florida created during his African American History class.

You talk about organizing this show, I’m wondering if academic art shows, like CFAM (Cornell Fine Arts Museum) shows, if you think that those shows serve the Orlando art scene as a whole.

That’s something that the Cornell really strives to do, create a space for the sort of complexity that we associate with the Orlando art scene. I think people tend to assume that the Orlando art scene isn’t very complicated. Aesthetically, perhaps, Orlando is closely associated with Disney, and Mickey Mouse cartoons, which, in a way, are actually quite complicated. They’re important, as a part of the American cultural landscape, but when people think about art, they’re thinking, in this context, about a particular narrow band.

Can you name any particular Orlando comic book artists?

You know, artist-wise… yeah, I don’t know that many artists. That’s one of the big gaps in terms of some of the stuff I’ve done. You know, I’m hoping actually in the next year to do more with comic artists in the community. If I have the opportunity to do a class in the spring, that’s going to have a big comic component. I’m hoping that we can figure out a way to create some opportunities to spotlight some comic art. We do a lot of community-based research so I’ll have to reach out and make some connections.

Are comics an art form?

I do think they’re an art form. For the Afrofantastic show we’re gonna have pages from Brotherman, a comic from the early ‘90s. Original pages by Dawud Anyabwile. I’ve talked to him, he’s going to loan us pages from the original Brotherman, which, you know, are these archival things, right? These are original pages, but we’re gonna put them up in a gallery! So, of course, his art in a gallery at this point is not an unusual thing, it’s perfectly reasonable. The intent around art and comics is clearer for people who know that part of the art world. So, if you are familiar with the influences of modern art, especially artists associated with street art, or graffiti art, or something like that, you know they often transmit or translate these sort of pop culture iconography from comics, television, movies, things like that. So you get a lot of art that’s not necessarily comic art, but it’s inspired by comics. You see a lot of that with hip-hop artists that use phraseology and characters and concepts that they borrow from comic books. A lot of them borrow stuff from like, the X-men, or the Punisher.

Cool! I can ask you a fun question now. In your TED talk, you mention Metropolis and Gotham, how they’re two sides of the same coin. Where does Orlando fit in that spectrum? Is it one or the other?

It wouldn’t be either. It would be like a Central City or a Midway City. Which is to say, if it was a DC city, it would be like that. Part of the reason I hold that the Metropolis and Gotham dichotomy works is that they’re basically just adjectives for a city and urbanization. Metropolis is a big city, Gotham is also a big city, but darker. If you look up the definition in the Oxford dictionary, they do tend to lean toward these definitions. Gotham is a big city but there’s this connotation toward it being more sophisticated. I was looking this up, actually, a while back. Gotham also references a city full of fools. A community of idiots, like, the dark ages, or something like that. Which actually makes perfect sense if you think about why anyone would live in Gotham, given how criminally dangerous it is. You could see living in Metropolis because the world’s most powerful superhero lives there. But, living in Gotham… the Joker lives there! And your superhero is just a guy! And all the villains there are super crazy. The superhero is just a human, and he only operates at night. That’s another thing, Superman is there all the time. Another thing about Gotham is its costumed villains, each of them has these sort of mental quirks, things that you associate with people that go crazy in the city. Obsessive compulsive disorder, anxieties around things that make them very dangerous, or just that they’re psychopathic. These are all things that people used to say would happen if you go to the city. It’ll drive you nuts. The nature of the nuts is embodied by these different characters. They are unable to love, they’re heartless and cold. Literally, you have Mr. Freeze. People in the city are crazy, Joker. People in the city get really twisted up and have really bad values, shit… Poison Ivy.

That leads me to another question. In one of your articles, you talk about 20th century heroes that sprung from “social exploitation, environmental spoilage, and urban disorder.” What kind of heroes spring from 21st century worries and issues?

I think you see heroes that are concerned with identity, the schism behind identity. So, there’s this fixation on inhumans in Marvel comics or in Marvel’s Agents of SHIELD on television. Like, who are you? Are you who you say you are? How your blood is sort of defining you. It’s a bit of a commentary.

You also see heroes sort of born out of technology, this sort of relationship between yourself and technology, this idea that they sort of integrated in the Marvel cinematic universe. Like, all the powers come from technology if you think about Iron Man armor, Captain America super soldier sort of biological experiment.

So… Which superhero do we need? Superman might go without saying, but if the world could pick one superhero, who could we use?

Good question. Maybe a good superhero to have would be like a Professor X? One that can help people understand each other, with the mental power thing. If it’s a question of symbolism, maybe a Wonder Woman would be really important? If you wanted to have only one hero, they’d be the symbol. You have this global question about gender inequality, and this question about peace, so, anti-war. These are some of the ideas that William Marston, the creator of Wonder Woman, was concerned with. He had many weird ideas, but one of the important ideas was this need for feminine power to constrain male power. There’s a lot of iconography of the original Wonder Woman that grows out of S&M-ish leanings. He was in a polyamorous relationship. He lived with his wife and his girlfriend, intimate with both. He believed that female power was this sort of check on male power and that it was important for males to learn to submit. From his perspective, there’s a really complicated relationship between gender and power. Teaching boys to submit to female power, that can sort of help them figure out their own power. There’s a real complexity there. Like, contemporarily people tend to view Wonder Woman as a warrior. That’s not exactly what Marston was advocating. Yes, she is very powerful, but she’s also this paragon of love and femininity, to say women can be powerful. But the constraining thing is like, “Good for you!” You’ve got the lasso of truth, and you think of telling the truth as being your best self.

That brings me to another thing I wanted to address and that’s how comic books reflect the world around them. How do you think about comics as a way to get social messages across?

Well, that reminds me there’s this new comic Black. I just got a preview copy, it’s based on the premise that only black people can have super powers. Just the premise alone, I thought about the concept of X-Men: “Oh they fear and hate us.” And I was like, “well they DO fear and hate black people.” So if they just had superpowers… well, that’s a good question.

In contrast, though, look at someone like Molly Danger by Jamal Igle. You wouldn’t know that Jamal was black just from reading it. You’d think it’s just the classic pre-pubescent superhero story.

I asked you about picking one superhero, but obviously, superheroes don’t exist. If you could enlist the help of one influential person in our world for Orlando, maybe a group, to make the city better, maybe do a project, who would you choose?

You know, I think a company like Boom or IDW. I think for someone to start a company like those in Orlando? That would be good. Also, maybe a company like Lion Forge, who has made a lot of success with making comic books off of Universal Television property. So like Airwolf, Knight Rider, Miami Vice, etc. But, none of those companies are like, huge companies.

The point is, we need one of those. If you think about it, the model for that kind of thing exists in Orlando. I would argue that you can look at a company like Burrow Press, the model that is Burrow Press, and you can replicate that in the comic world. I think there are enough talented people in Orlando and the metropolitan area. You need to create a space for them to do this, and an awareness for the opportunity. There’s not a shortage of talented people in Orlando. There are a shortage, sometimes, for vehicles in which that talent can be on display where an audience can appreciate the talent. If we had a comic book company in Orlando, it would need to cultivate that space. In that gap of what Orlando is, and what it could be, I can see that. I think there is a thing where you don’t see this clear inter-generational support that you might see in other major cities, where there’s people at the bottom of the system, and at the top of a system, who forget they’re in the same system.

I think we have some of what we need. We have resources like the CFAM, who will give public tours and talk about the contemporary art that is featured. We have a public institution, the OMA, whose broad size and scope can help them do a lot of things. Then you have the Downtown Arts District, with galleries like Avalon. So I think there are spaces for everyone to be active. When you have a magazine like Artborne, it becomes a touchstone for a lot of these discussions, like, “What do we want from art?” You know, is Artborne going to be read by everybody in Orlando? Or is it going to be the arts people in Orlando?

So, that’s a really important question. If your goal is to grow the art scene, then you kinda have to tow that line between it being cool and slick, but also accessible. What can you do to move people up in their understanding and their engagement? You need vehicles like an art magazine.

On that note, let’s wrap it up with a nice, easy question. What is your mantra?

Haven’t gone far enough. I sometimes ask myself, “Why didn’t this work out? Have I gone too far?” Invariably what I find is no. Didn’t go far enough. When the ideas get really crazy, don’t think “Have I gone too far?” You haven’t gone far enough.

I couldn’t just leave it at comics, that was to limiting the full picture of this great professor. Julian’s efforts in activism are an important part of his story.

Considering the news media simply focused on the controversy, the outrage, and the protest against his involvement in the John Sims’s project, no one was getting the full scoop unless we got his story firsthand. Julian was happy to oblige, and his true opinions of the event, the factors surrounding it, and what it means to America will surely have you thinking hard about the role of historical symbolism in modern society.

First, how did you find out about the protest, and what made you want to get involved?

Well, I was asked to be involved by John Sims. He’s the artist that conceived of the project. He has an established project called the Recoloration Proclamation. A few different projects regarding the Confederate flag. He’s recolored the flag. He did a show in Harrisburg, PA in 2003 or 4 where he hung the Confederate flag (with nooses).

He reached out to people to organize this flag burning across the South, in the former states of the Confederacy. Thirteen flag funerals. When he asked me to do the funeral for Florida, I already was aware of the anniversary of the Civil War. I was aware that there is a contested meaning around the Confederate flag. So, I understood; I said yes. It sort of jives with my own understanding of the complexity of the flag.

Were you worried about the backlash, or did anyone close to you speak out about it?

People spoke out, in the sense that they were worried for me. Because, you know, the Confederate flag is a flag that is full of, in my mind, a false narrative. Most people of color, or white people, who recognize this false narrative usually hold their tongue. They don’t go around telling people they don’t believe in that kind of willful ignorance. So whenever you’re challenging the flag, you’re basically challenging white supremacy that relies very strongly on shouting down, not necessarily violent things, but aggressive things.

The threats were… just that, threats. Nothing like being in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s.

Threats, you say? Were there specific threats or was it just the idea that doing this could be threatening?

No, no… people threatened me. People would call my office. People would send these angry, angry e-mails. People said they were going to come to the event with guns. It was all over these white supremacist boards with violent imagery, and so on. It was a real threat, not imaginary. There were real threats. At the end of the day, I think that forced some people to come. Some of my friends who weren’t going to come were like, “Well, I’ll come now.” So, ironically, on the day of, many people showed up, but at the wrong place. On the day of, I heard about all the angry people who were “looking for the n-word that was gonna burn the flag.” They were at the Greenwood Cemetery, but the day of? I was at the Urban Wetlands Project, so I never saw any of them.

Do you think that the general media has had misconceptions about this?

Oh, yeah! Of course! News media is ill-equipped to talk about why we burn the flag. For the news media, it became about how I was upsetting people. They couldn’t talk about how it’s a disruptive, regressive symbol that does not represent what they pretend it does. The story is not my ideological position. I’m burning the Confederate flag. I feel like if it were the American flag, people might not notice at all.

Can you speak to the idea that the Confederate flag is “holding us back” as a country?

Numerous times, people have asked me why I buried the flag. It is a regressive, repressive symbol that does not represent the ideology and political context of the contemporary South. Regression, here, means that it is tied to backward social/political/economic perspectives. That flag does not represent today’s South. There’s a lot more diversity, a lot more black people, Hispanic people. This is not a society that’s built on white supremacy, it’s a society that is more diverse in every way imaginable. To say that the flag defines how we should conceive of southern society is ridiculous for a variety of reasons.

The Confederate flag is a symbol of defiance in the face of reform. The idea is that “we don’t want to change, we want to be a white supremacist society, we don’t care that we lost the civil war, we still love the Confederate flag.” The symbol is resistance. The heritage that you’re celebrating is, “Oh, I fought a war to keep slavery.”

It’s treasonous, isn’t it?

Well, yeah. It clearly is treasonous. Now, the mythology around the flag is very different. The facts around the flag are set in stone. People ask me [if I know] all the time, but they’re just upset about the history. No, I know the history. The history is settled. You fought the Civil War, you lost. You had a slave society that was proven illegitimate. That’s why they fought the war. That’s why slavery was abolished after the war was over. That’s why they had reconstruction, because they wouldn’t let it go even after they lost the war, and it’s with political wrangling after reconstruction, that they were allowed to create a system that basically reaffirms white supremacy.

The history of the Confederate flag isn’t the question. The question is all the bits that were created after the war to justify the southern slave society, the white supremacist order. This leads to a mythology tied to the South where the war wasn’t fought about slaves. It was.

At the very basic level, familial history is represented by descendants. You represent your family. Symbols don’t represent your family. The Confederate flag doesn’t represent southern families. I’m a southerner, I have a southern family. That flag doesn’t represent me. You can’t say that a flag that is tied to white supremacy and terrorism also represents all of the South.

If you say to me, the Confederate flag is a symbol of white supremacy predicated on violence and systematic discrimination— I’ll agree.

If you say to me, the Confederate flag represents all of the South— that just ain’t true. That’s not how representation works. It might be something you associate with the South, as is any historical touchstone I can associate with a time and a place.

There’s a hundred things you can say, but at the end of the day, my point about what the flag stands for remains. It’s a regressive symbol tied to backward ideologies defining the South.

Photos (unless noted) by Jason Fronczek

You can see more at:

JulianChambliss.com