Portrait painting is one of the oldest forms of the medium. During the Renaissance, portrait painting became the standard requirement for all painters. When looking back through history, we view the elite exclusively through the gaze of the painter. Without these skilled artists, we would have no visual representation of prestigious historical figures.

The Kill, oil on linen

In the age of contemporary art, it is rare to find a technically skilled portrait painter, but that is exactly what Rima Jabbur does. Using her classical training, she creates life-sized portraits and striking narratives. The first piece we looked at in her expansive studio space was a jarring image of a hunting scene. This piece, which is 60” wide and 50” tall, depicts the moment a hunting party inspects the animal that they have killed. Jabbur has been on multiple hunting trips in Africa, but has never participated in the act of hunting herself. In this painting, Jabbur has recreated the decisive moment. Working with a video still as a reference, she turned the pixelated frame into a flawless oil painting. Standing in front of the image, it is not only reminiscent of a crime scene, but it also appears as if you are part of the hunting party, lighting the scene with a flashlight. With a medium like painting, it is easy to take an image based on reality and turn it into an illustrative work, but Jabbur strives to create truth through her paintings.

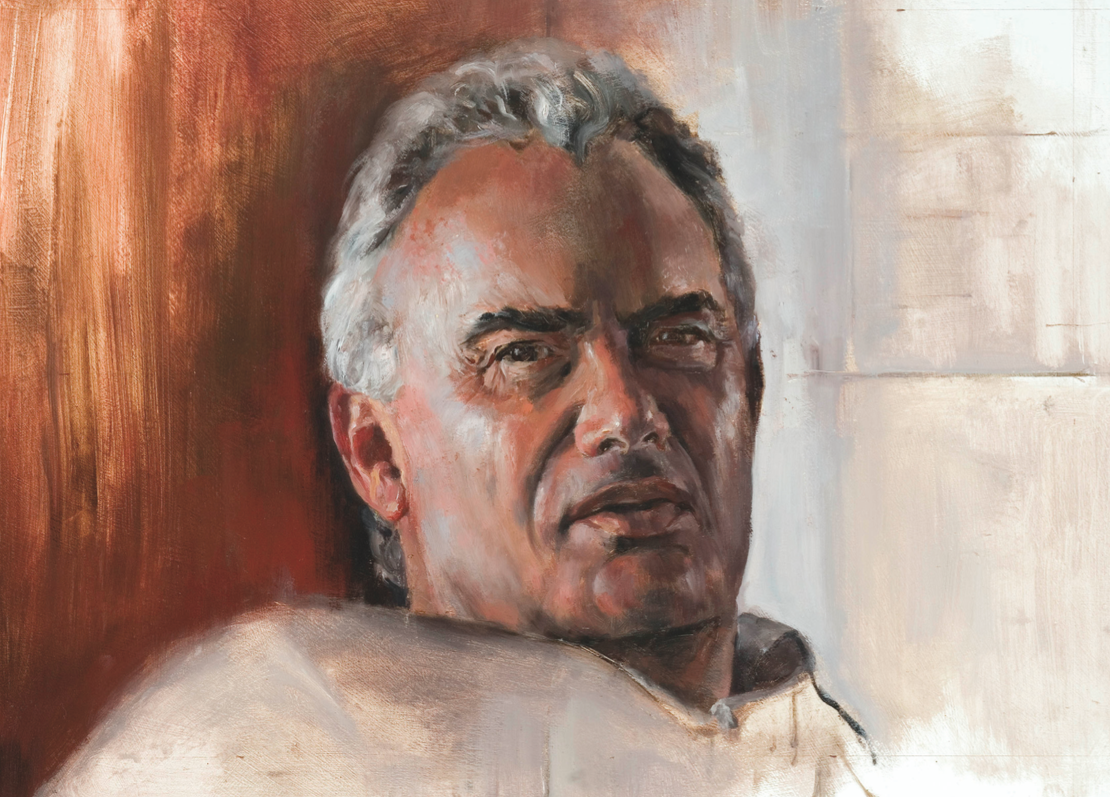

Walid, oil on panel

Study of Tara, oil on prepared paper

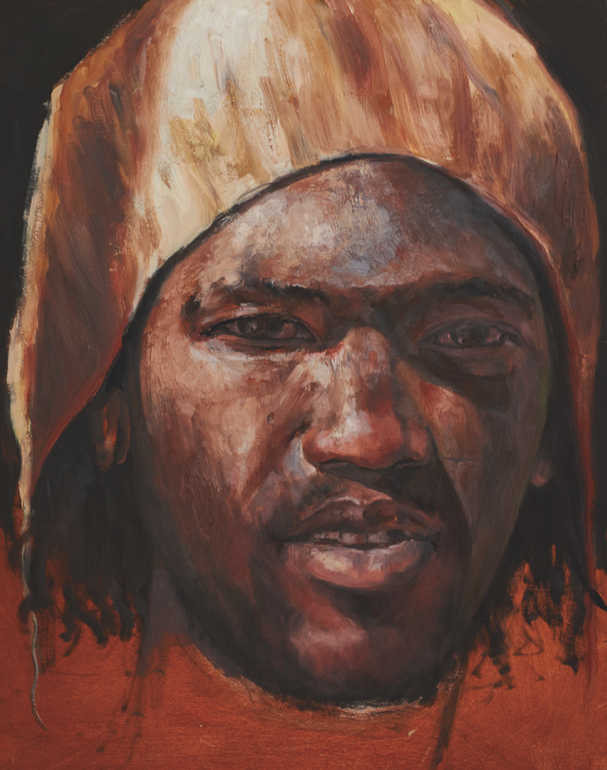

Especially in her portraiture, truth becomes an element of the painting itself. Jabbur refers to these paintings as “psychological portraits.” Through her portraits, she reveals elements of the model’s character. Working exclusively with people who intrigue her or have a connection with her allows Jabbur to reveal deeper levels of the individual. When searching for a model, Jabbur is not necessarily searching for someone who is classically beautiful, and sometimes it takes months to find the perfect person. “The reason I love portraiture is that I get to live with that person for a while,” she explains. Not only is portrait painting an intimate and vulnerable experience for the model, but Jabbur explains how the artist is vulnerable as well. When painting from life, not only are you looking at the model, but the model is also looking back at you, watching the artist while they work. That can be a lot of pressure for an artist. For her process, Jabbur invites the model to her studio space, works with them in person and photographs them in multiple ways. “The photo is just a point of departure, I don’t copy the picture,” she explains. Elements of multiple images are used to create the final painting which may not look like the photograph at all. This is a time consuming process and by doing so, Jabbur is able to see more of her model’s personality before the painting has even begun.

Gaby, oil on linen

For her large paintings, Jabbur’s process begins with charcoal. “Drawing with charcoal is liberating,” she explains. “If something isn’t working, I can just wipe it out with a cloth and try again.” Unlike oil painting, there is no preparation and cleanup when working with charcoal. She can spend a few hours drawing and walk away, not having to worry about her materials drying up. The back corner of her studio is covered with charcoal sketches. Elements of other paintings in the works can been seen drawn out in black lines. It is not uncommon for Jabbur to combine multiple sketches to make up a painting. Before the painting begins, she will hang two pieces next to each other and view them as one to see if the idea can successfully translate into painting.

studio shot of studies of works in progress

Although she is mostly known for her oil paintings, Rima Jabbur does complete work in charcoal as well. In December 2016, she participated in Cornell Fine Arts Museum’s exhibition Displacement: Symbols and Journeys. The show featured the works of artists who have been relocated from the country they were born in. Jabbur, who moved from Syria to the US when she was eight, displayed a charcoal and blood-red piece consisting of three prominent elements. The top of the image depicts two faces of the Hindu goddess Kali, with her tongue sticking out in shame. Underneath the image of Kali are two groups of soldiers that are almost identical, but one group represents ancient Syrian warriors, while the second group of men is dressed in modern garb. “War will never stop,” Jabbur says, describing the piece. “Hindus view war as a necessity for change, and Americans view it as a tragedy. I identify as an American, which gives me a different perspective on the world.”

Time of Kali, charcoal and watercolor on paper

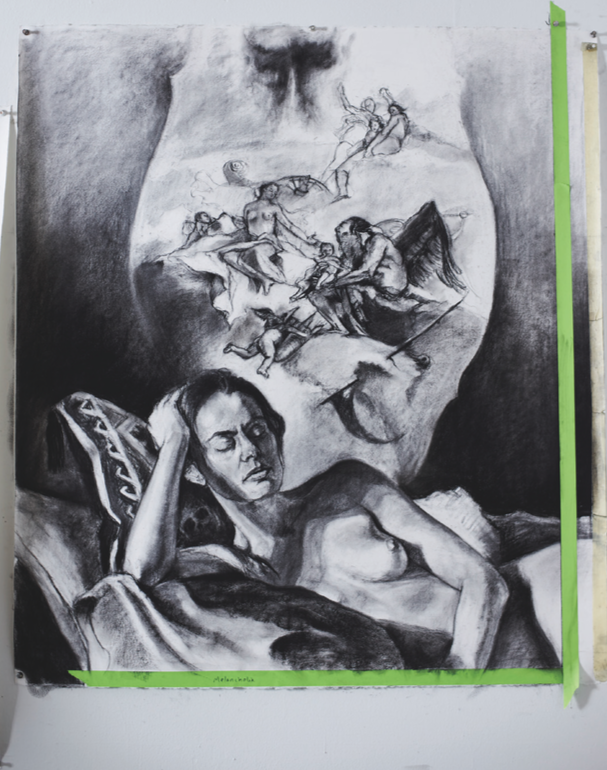

Typically, Jabbur strays from painting about political issues, but lately they have seemed to leak into her work. “I don’t consider myself an activist or see myself as someone who creates political art,” she explains. Because her paintings are such a production, Jabbur’s subconscious has the opportunity to slip into her works, sometimes without her even noticing until the painting has been completed. While in the studio, we discuss one of her works in progress, which she explains is about the circle of life. The piece shows a reclining woman—a classic motif in paintings—dreaming. The whole upper register of the painting represents a dream, which is an appropriation of Giovanni Battista Tiepolo’s An Allegory with Venus and Time. Jabbur’s interpretation of Tiepolo’s piece subtly adds elements of modern war. Her home country of Syria continued to be on her mind while she was creating this piece. “I never thought what was happening in Syria could ever happen. It is weighing on me,” she admits. Adding elements of modern warfare to this painting about fertility and death was a struggle. It is very easy for a painting to become too illustrative for Jabbur’s personal style. When struggling with a painting, she gives it time to breathe by either drawing with charcoal or working on one of her many in-process, labor-intensive paintings.

Study for Where Do We Go, charcoal on paper

Where Do We Go, oil on linen

Because of the scale and amount of detail that go into her paintings, Jabbur spends countless hours in the studio to complete a single work. “It is extremely helpful to have deadlines,” she says. “Sometimes it is easy to spend too long on a painting. Deadlines help make the final decisions.” These deadlines come from shows and exhibitions that Jabbur displays her art in. She currently has work displayed at the Orange County Commission Chambers for their Art in the Chambers show. She has been publicly showing her work since the 1990s and enjoys every second of it. “I want people to see my art. It comes to life in a new way.” The only downside of having a private studio space, for Jabbur, is the lack of interaction. She reminisced about the days that she was able to talk to peers while working on projects in a shared studio space, but now, as a painting professor at Valencia College, she is surrounded by other working artists who are more than willing to give feedback.

Inhaling and Exhaling, oil on panel

Boustany Twins, oil on linen

Over the course of her career, Rima Jabbur has had multiple solo shows, including one at Cornell University and one in Beirut, and has been a part of numerous in group shows across Florida. Lately, she has been pining for another solo show in Beirut. She has also been looking into galleries in New York City for representation in the United States. Traditional portraiture may not be the most popular form of painting, currently, but it is a style that will never be obsolete. “Everyone is interested in the human form,” Jabbur states. “It always comes back to people.”

Study of Tulani, oil on panel

You can see more at: RimaJabbur.com