When I first contacted Dana Hargrove, she politely informed me that she would be camping for the following four days and would not have access to WiFi until she returned home. The thought of being completely disconnected sounds amazing, but it is also a frightening thought. Unplugging has become more than just an action; it is now also a state of mind. More people could benefit from cutting themselves off from instant fingertip access to the world, especially before elections. In Central Florida, we are only an hour from beaches, natural springs, nature trails, multiple state parks, and so many lakes. Hargrove, unlike most of us, makes time to escape the concrete and appreciate the beauty of her surroundings—while they are still left mostly untouched.

As a conceptual artist, Hargrove addresses the issues of consumerism vs. nature, and displacement. She uses multiple mediums such as painting, photography, video, and sculpture to create visually fun works of art with deeper meaning. Born and raised in Scotland, Hargrove moved to America to pursue her MFA. The drastic culture change was not easy for her to adapt to. Her work up to that point was site-specific and driven by the natural beauty of her surroundings in Scotland. Of her new life in a college town in Southern Illinois, Hargrove explains, “I wasn’t feeling confident in my surroundings. I didn’t know the history.” It took her a while to understand the culture of this new place. The site-specific work that she had created in Scotland was now considered graffiti and a crime. Turning to more traditional forms of art helped Hargrove cope with her displacement, and also helped her become “rooted” in her new life.

In America, we are taught to be unauthentic: smiling at strangers for no reason other than to be polite, complimenting a stranger’s appearance, and making small talk of weather and politics while in line at the grocery store. Hargrove was taken aback by all of these traits—which on the surface seem inviting and friendly—but the invitation for friendship is never extended beyond these so-called polite encounters. This façade can be found in all aspects of American culture. Old buildings get fresh coats of paint when rustic bricks become exposed, and in some cases they are completely torn down and replaced with something shiny and new. Architecture is completely contrived in the United States; cookie-cutter neighborhoods of prefab houses can be found all over the country for our friendly Americans to live in. The only thing that changes in neighborhoods across the nation is the landscaping. Hargrove has explored digital manipulation—or enhancement, as she calls it—to photography as a way to give new meanings to the landscape surrounding her. Using her neighborhood as a subject, she began to view America as home, and she slowly started to take root.

Facade 4, acrylic on panel

Unlike Scotland, Illinois did not offer Hargrove lush landscapes with rich histories. In an effort to become rooted in America, she began to research her new home. As a country, America’s history only goes back a few hundred years, but if we have learned anything from Alfredo Jaar, there is more to America than the United States. When Hargrove moved to Central Florida to teach at Rollins College, she explored and studied her new surroundings. It is a personal goal of hers to discover new places every year, both in America and Scotland. The world offers so much history; we just have to be willing to take the time to seek it out and learn from it.

One of Hargrove’s favorite local landmarks to visit was the three-thousand-year-old cypress tree fondly known as “The Senator,” which burned down due to arson in 2012. The tree had acted as a landmark long before central Florida became an urban city; Native Americans had used it as a marker for meetings and trails. Hargrove visited the tree shortly before its destruction and described how she felt when she found out that the oldest bald cypress tree in the world had been destroyed: “A human life consists of a fraction of the time that the world has been around.” Placing herself as a speck on The Senator’s timeline was a humbling experience for her.

Nature is a recurring theme in Hargrove’s work, whether the piece is a visual representation of nature, or the lack thereof. Her objective is to provoke conversations about the environment and how it is changing. “What amazing places are right there on your doorstep?” Hargrove asks. It is so easy to get caught up in the vicious cycle of working for a living that you forget to look. In her art, she uses a beautiful combination of vibrant and pastel colors and natural forms juxtaposed with linear perspectives. In this way, she addresses the delicate balance between nature and culture. “Linear perspective is not something that happens naturally,” she explains. Linear perspective can only be found in landscapes that contain something manmade, like roads or buildings; it is created by urbanization.

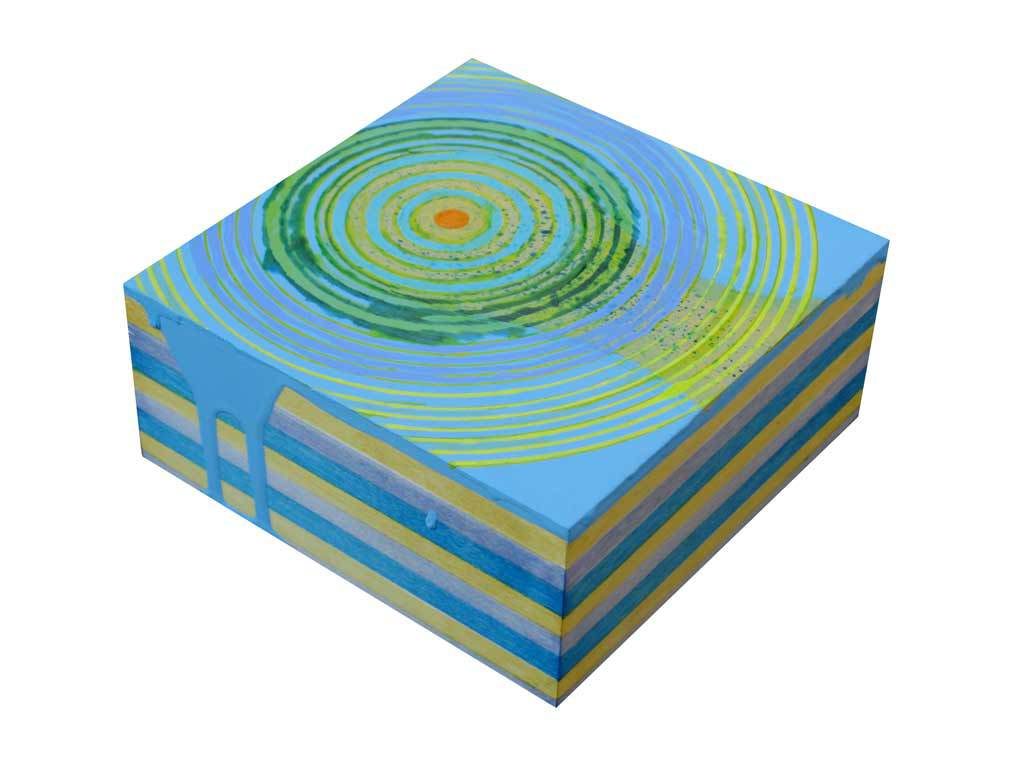

Absentia #1, acrylic on beech plywood

Hargrove’s series Absentia is a graphic example of linear, geometric shapes combined with organic forms. Her colorful “cairns” seem impossibly held up when viewed straight on, but Hargrove reveals her secret and allows the viewer to see the backside of these sculptures, which are propped up with simple supports. Acting almost as parts of a set, the pieces within the series are arranged in such a way so that “the pieces can have a conversation with each other.”

Currently, Hargrove is working on pieces for Art in Odd Places. The theme of this year’s exhibition, which spans downtown Orlando, is “Play.” Her pieces are playful in nature, but they also carry heavy social meanings. These constructed sculptures, similar to the ones created in Absentia, will be set in the most undesirable corners of the city. Like traditional Scottish cairns, these geometric stone mounds act as miniature landmarks of displacement. With this work, Hargrove hopes to bring some joy to the individuals living on the streets downtown, while drawing attention to areas that would normally go unseen.

The Multis, acrylic and indian ink on cardboard

Cairns frequently appear in Hargrove’s artwork—drawings, paintings, sculptures, and photographs all feature these iconic Scottish landmarks. She describes them as “assembled mounds of gathered rocks, hand-built stone by stone through the centuries by locals and visitors to memorialize their summit or journey.” This ancient Scottish tradition has been carried around the world, and now Hargrove is bringing her unique interpretations of cairns to Central Florida.

Another Scottish tradition that she takes notice of in her work is golf. In her series War/Game, she combines symbols from the game of golf with international symbols found on military maps. The tiles that comprise the series work as individual pieces, or can be put together to create a larger map. The vibrant blues and greens chosen for the landscapes are rarely found in nature, yet they convey a sense of natural beauty. These unnaturally perfect colors translate well into the larger golf map, since golf courses are confined areas of manmade nature. When the sport began in Scotland, the early golfers used the natural landscape as a course, but over time the landscape was altered to accommodate the golfers. In 2010, Donald Trump purchased a large, protected portion of Scotland’s coast that he planned to turn into a golf course and luxury resort.

Before 2010, the site that Trump purchased was a sacred tract of land that was open to the public, but Trump managed to get his way, and, against the local people’s wishes, the protected four-thousand-year-old sand dune system was destroyed. After years of bullying locals and befriending the local police department, Trump’s plan succeeded, and the naturally beautiful scenery became a contrived landscape. Scottish natives that had lived near the dunes for generations were forced off of their properties. Their water and power were shut off, property was damaged, and one man even lost a portion of his historic home. But even after beginning construction and destroying the dunes, Trump threatened to abandon the project because he did not approve of the wind farm that was going to be located within his view. The documentary You’ve Been Trumped, which deals with these events, was released in 2012, and Hargrove was able to view the film in the UK. There was a strong reaction to it, and she reminded me how much people in Scotland dislike Trump. She also informed me that this is the first year that she is able to vote in the United States presidential election.

Facade 5, acrylic on panel

Hargrove became interested in the concept of golf courses when she realized “golf courses can be anywhere in the world. You can visit them all and not experience the world. A golf course in Florida can be made to look just like a golf course in Scotland, or China.” Hargrove manages to draw a connection between golf and war through the “applied rules and order to the landscape.” Both take what is natural and dig out dunes and trenches, creating a manmade landscape. Globalization and capitalization are apparent in both golf and war. “Capitalist greed is taking over nature,” and, because of so much urbanization, Hargrove describes how one can easily forget what the real landscape looks like. By combining international war-map markings with artificial aerial-landscape views, she transforms her manicured, beautiful paintings into something much darker.

“Art is a good venue for conversation,” Hargrove explains. But even the experience of viewing art is at risk of disappearing as well. The gallery that represents her, Bridgette Mayer Gallery in Philadelphia, has become a private gallery and will no longer hold public shows. It is becoming more and more common for galleries to turn to this model, or even to become completely online businesses. Viewing work online compared to viewing it in person is a completely different experience. “When I was first starting out, social media wasn’t a thing,” Hargrove tells me. Having an accessible website with images of work is important for artists today. She does tell me that she has enjoyed posting images to Instagram. It has given her the opportunity to revisit and share old bodies of work that have not been viewed online before, but social media can only go so far in representing an artist’s work. Seeing Hargrove’s works in person allows the viewer to have an experience with the pieces that gets lost when viewing on a screen. In Central Florida, we have the opportunity to experience all types of art, and, like nature, it can often be enjoyed without the use of technology.

Arcadia ii-vii, acrylic on beech plywood

For Hargrove’s series Right to Roam, photographic images do not do the pieces justice. These images exist somewhere between painting and sculpture. She starts the creative process by making two-dimensional sketches, and then digitally selects the colors that she will use for the painting. The sculpture is made next, and lastly it is painted. When viewing these three-dimensional sculptures as photographs online, they appear to be flat paintings. Hargrove’s graphic painting style makes the pieces difficult to distinguish that they are three-dimensional, but seeing the pieces in person allows for an interaction that would not happen otherwise. Having the ability to move around the piece freely is something that an online interface cannot provide. Interaction is an important aspect of Hargrove’s art, which represents community. The Right to Roam series uses a variety of colors and modular shapes that come together to create one unique work of art. Viewing the works from different angles can make them appear slightly different, but because they are hanging on a wall Hargrove’s art is approachable. These pieces can be read as cairns or buildings, but either way they represent landmarks that require a community to create them.

Circuit Map, mixed media on panel

Currently Hargrove is on her second sabbatical with Rollins College. She is excited to be able to participate in this year’s Art in Odd Places, and her work will be exhibited both locally and internationally through the end of the year. By exploring nature, community, and consumerism, she has been continuing old bodies of work and creating new conceptual work. “Art is difficult, and that’s okay.”

Being an artist is not an easy task, and it is a job that lasts a lifetime, but sometimes consuming art can be difficult as well. Like American culture, Hargrove’s work gives off a friendly appearance while containing deeper meanings, but if by studying her work you do not see anything beyond the surface of paint, she is okay with that.

You can see more at: DanaHargrove.com