As a museum curator, I feel a responsibility to create exhibitions that reflect current events and echo themes of social justice. I aim to create projects that elicit conversation, debate, and reflection. I never want people of disparate political beliefs to feel unwelcome in an exhibition I have developed. A museum is a public space where visitors can assert some sense of agency in their interpretive process. Visitors are not required to listen to a tour guide or read the labels or look at every work on view—you can, but only if you wish.

A routine walk through the galleries at any institution can yield powerful feedback about the art on view. You can hear laughter, criticism, confusion, and witness visual engagement just through observing the people who visit the galleries. As a curator in an academic setting, I often receive students’ candid, invaluable feedback. Recent questions from student visitors include: “Why is one man’s abstraction more important than another’s?” “Does the fact that the artist had assistants make his work less important?” “How are you planning to commemorate the tragedy that occurred at Pulse?” The answers to the first two questions flow easily for me. The answer to the third remains elusive. It can be challenging to curate projects about topics that feel too close, too raw, and too emotional. I admire colleagues who are able to react quickly; my projects tend to evolve over longer periods of time. I find myself needing to go through a process in which I question every decision before a show comes together. This process remains especially important for me when working with political art.

Hugo Crosthwaite, Bartolomé, 2001, graphite and charcoal on wood The San Diego Museum of Art Image courtesy of the artist and Luis de Jesus, Los Angeles

My interest in movement across the Mexico/U.S. Border led to the opportunity to work with the artist Hugo Crosthwaite in 2010. Crosthwaite’s compositions are informed by the history of art—his artistic influences include street art, Francisco de Goya, Diego Velásquez, and José Guadalupe Posada, among others. His rendering of figural forms evokes the technique of Old Master painters, but his subject matter functions as an amalgamation of daily life experience in Tijuana to the political events and realities that disturb him. Crosthwaite’s Bartolomé was made while the artist was listening to reports on NPR about the abuses that took place at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. Crosthwaite alludes to Catholic tradition in his reference to Saint Bartolomé, known to followers as a martyr whose skin was flayed. In the foreground of the composition, anonymous hands emerge from nowhere and pull the skin away from a central figure. Some of the figures depicted are badly beaten and others are hooded, evoking the highly-reproduced photographs of prisoners with shrouded heads. Here, the artist conflates time and history. His testament to the pain experienced by these prisoners becomes more tangible as Crosthwaite’s figures are rendered before the backdrop of his beloved city of Tijuana: home to many who struggle with economic inequity, and who remain resilient in the face of drug violence and American visitors who treat their city as a playground. The atrocities of war are difficult to understand. Armed conflicts of the past and present demand reflection.

Michelle Dizon, Basing Landscapes, video, 2013, running time, 50 minutes, Image courtesy of the artist

In 2014, I curated an exhibition titled Women, War, and Industry that examined the myriad ways in which women have been represented in relation to war and industry. During the twentieth century, both the advent of war and increased industrialization led to major changes in the lives of women: their roles in their families, the way in which they dress, and the manner in which they are perceived in the public sphere. There are iconic, historical, and fictional ways in which women have been represented in relation to the complicated and intertwined factors of war and industry. This exhibition presented a historical trajectory and included World War I and II posters and the trailblazing work of American photographers like Margaret Bourke-White and Esther Bubley. Bringing contemporary artists into the discussion of women, war, and industry seemed appropriate given current events. Works by Miyoshi Barosh, Any-My Lê, Pae White, Catherine Opie, and Iana Quesnell were featured in the contemporary portion of the exhibition. Video artist Michelle Dizon, who lives and works in Los Angeles, made a new work for the exhibition titled Basing Landscapes, which presents haunting scenes of abandoned U.S. military bases in the Philippines juxtaposed with interviews with female sex workers who have experienced violent encounters at the ends of American visitors.

Yoan Capote, Abstinecia (Libertad), 2014, cast bronze and engraving and drypoint, Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art, Cornell Fine Arts Museum

©Yoan Capote. Image courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery

Since joining the staff of the Cornell Fine Arts Museum at Rollins College three years ago, I have been able to develop group exhibitions such as Fractured Narratives (co-curated with Abigail Ross Goodman) and Displacement: Symbols and Journeys which presented political work addressing diverse issues, from the use of drones to immigration. Beyond these temporary exhibitions, consistent presentations of socially engaged work occurs in the museum’s permanent collection gallery and at the Alfond Inn. At the Alfond Inn, works by artists such as Yoan Capote and Jenny Holzer draw visitors in with a sense of awe. While both artists produce visually intriguing works, deeper political meanings resonate beyond the initial aesthetic impact. At an elegant hotel, as opposed to a traditional museum space, the surprise encounter with a political work becomes amplified. Capote’s bronze hands spell the word “freedom”—or libertad, in sign language. The models for the hands were Latino laborers. Across cultures, classes, genders, and individual experiences, freedom means different things to different people. Political art does not always have answers; sometimes, it simply questions.

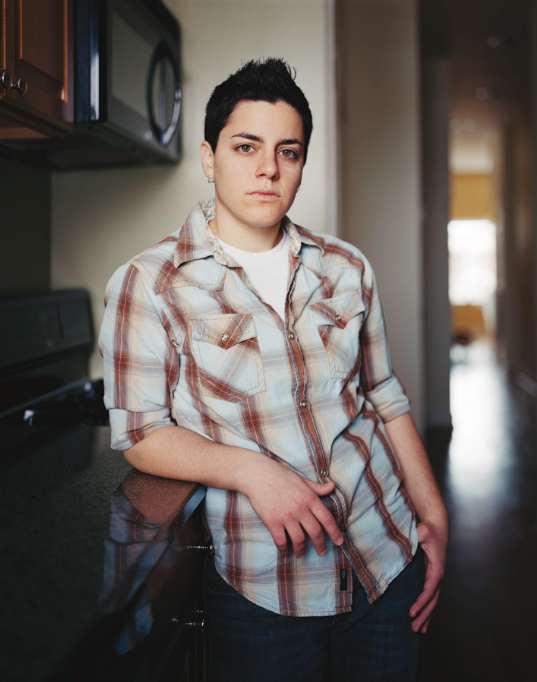

Jess T. Dugan, Betsy, 2013, pigment print Cornell Fine Arts Museum

Image courtesy of the artist

During a class session on portraiture, some students really struggled with a portrait by Vanessa Bell (currently on view as a part of the exhibition This Side of Modernism). They questioned its validity as both a modern representation and as a successful portrait. Instead, they were drawn to Betsy by Jess T. Dugan. For them, Dugan’s portrait offered the intimacy they wanted between subject and artist. Moreover, many stated they saw themselves in Betsy and the medium of photography felt accessible. In 2015, after presenting the first museum exhibition of Dugan’s photographic series, Every Breath We Drew, I could not agree more with their positive assessment of the photographer’s work. Although I did not agree with the students’ assessment of Bell’s modern picture, I embraced their energy. They saw in Dugan’s work a commitment to what she describes as “visual activism” and they responded to her dedication in seeking dignity for her many of her subjects, who identify as LGBTQ and have often experienced marginalization. As Dugan brought her subject into the public sphere, viewers of her photographs who see themselves in her subjects could feel recognized and valued too. After all, being seen and feeling respected are universal desires.

Every day presents new challenges, new responses to work, and new opportunities to expand the conversation. I hope that certain exhibitions spark conversations and provide an opportunity for reflection. Museums can provide a space to foster community, when the events unfolding before our eyes shock us, hurt us, challenge us, or simply make no sense at all.

You can see more at: Rollins.edu/cornell-fine-arts-museum