Communion Photograph Series, giclée print

“Naming suffering, exalting it, dissecting it into its smallest components—that is doubtless a way to curb mourning.” —Julia Kristeva, Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia

Shelby O’Brien acknowledges the horrors of the human body in abject memorials, crafted using human blood in traditionally domestic material processes such as candle-, soap-, and candy-making. O’Brien became acquainted with the ephemeral nature of the human body and its physical existence at a young age, witnessing her mother’s struggle with chronic illness, and then while facing her own mortality as she underwent a hysterectomy in December of last year at the age of 25. Profoundly moved by these experiences, O’Brien focused her artistic practice on confronting physical impermanence in a death-denying society while continuing her family’s legacy through heirloom traditions.

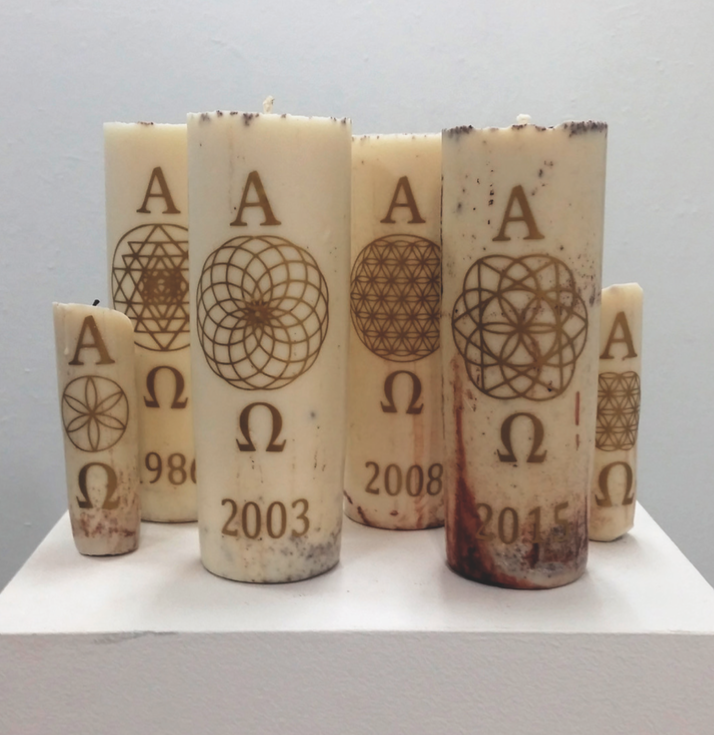

Paschal Candles, Soy wax, paraffin wax, peppermint oil, lemongrass oil, human blood, and vinyl

When faced with the decision to go forward with a hysterectomy during her second year of graduate school, O’Brien began experimenting with canning and preserving in her studio, informed by childhood memories of her family’s tradition of canning garden vegetables in the summer and her own desire to “hang onto whatever is left for as long as you can.” She filled vintage glass canning jars with clear toy candy (a traditional Pennsylvania Dutch recipe), ephemera from her previous medical interventions, as well as blood belonging to her mother and herself, collected during routine appointments with a phlebotomist. The resulting works are poignant memento mori, memorializing a traumatizing event particular to the artist’s life while gently teasing our attempts-in-vain to defy death as human beings.

Communion Photograph Series, giclée print

While her studio experiments with canning were motivated by a desire to preserve, O’Brien’s chosen materials all contain metaphors for the ephemeral nature of life, as well—consumable candies, melting wax, and disintegrating soaps. For a recent series of sculptures, the artist was influenced by Christian and Catholic rituals relating to life, death, and resurrection and their symbolic, material manifestations. Again, using her own and her mother’s blood, she created Paschal candles inscribed with dates representing surgeries, accidents, and diagnoses from her and her mother’s personal histories, referencing the traditional use of Paschal candles during Easter, baptismal, and funerary rituals.

Your Blood, My Blood, Our Blood, clear toy candy (sugar, corn syrup, water), human blood, traditional canning jars

Memorials often valorize the dead and provide comfort for the living, turning away from the decaying body and toward the spiritual and symbolic, offering hope of an abstract eternity. O’Brien’s memorials, however, decidedly enter into the realm of abjection, confronting the fragility of the human form with its biological reality. In her 1982 work, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, Julia Kristeva wrote, “A wound with blood and pus, or the sickly, acrid smell of sweat, of decay, does not signify death…these body fluids, this defilement, this shit, are what life withstands, hardly and with difficulty, on the part of death. There, I am at the border of my condition as a living being.”

O’Brien’s memorials, in their exaltation of the physiological processes that make death an inevitable part of life, are elegant and poignant, personal and universal homages to these conditions of human life.

You can see more at: ShelbyOBrienArt.wix.com/shelbyobrienart