Dawn Roe pulled a cardboard packing box from beneath a light table in her home studio. She kneeled and opened it gently, placing her hand on the pile of twigs, branches, bark, and berries within. “A friend from Michigan sent me some bits of a yew tree…”

Goldfield Study (Gold Paper and Tree, Part 2), Pigment Print, 2013

The artist keeps close to her heart an “appreciation of poetic sensibility,” picking apart language and relating it back to imagery in her photo- and video-based studio practice. Lately, this has manifested in an almost-formalist reconsideration of the photograph’s obvious potential for an indexical relationship with our perceived reality—Roe is moving away from documentary-style, realist photographs, and into the realm of combining processes (such as imprints, cyanotypes, and a continuation with video) in explorations of the camera and photographic processes as optical tools, rather than documentary ones, conveying the ambiguity and uncertainty of something like a feeling or a perceived moment, rather than a specific and identifiable subject. Undermining a strict formalist interpretation of this approach to photographic processes, however, is her specific choice of the yew tree as a subject in this new work, with an awareness of it as a symbolic signifier of death, its physical toxicity, and the significance of its place in history and literature.

Goldfields (installation view), Screen Space Gallery, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2013 (image courtesy of Screen Space Gallery)

Goldfield Study (Digging, Part 3), Pigment Print, 2013

Roe’s interest in the yew tree as a symbol as well as physical material is rooted in her ongoing research and fascination with Virginia Woolf’s experimental 1931 novel, The Waves, which has inspired recent explorations into this new body of work. One passage, which conjures an image of a yew tree in a metaphor for the brevity of life, ignites Roe’s creative process: “Let us stop for a moment; let us behold what we have made. Let it blaze against the yew trees. One life. There. It is over. Gone out.”

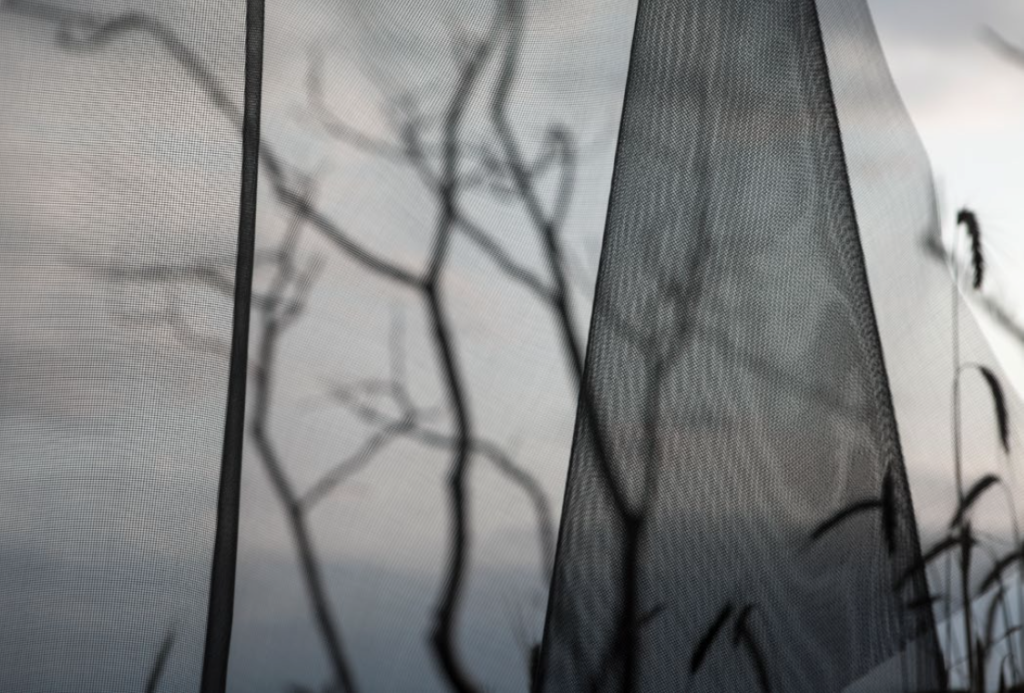

In her 2016 work, The Sunshine Bores | The Daylights, Roe combined audio of a melancholy soprano singing the piece’s titular phrase with footage of a single dead tree against a gray sky, an ambiguous view of a hanging screen ripped from a window, looking out from the prism viewfinder of a large format camera, and views from a lonely, mountainous highway, inter spliced with text taken from Woolf’s The Waves. The video ends with a black screen revealing white, all lowercase Courier text simply reading “in memoriam.” Roe said about this work, “I see it as functioning as part elegy, part perceptual study,” echoing Roland Barthes’ seminal 1980 work Camera Lucida, which was both a theoretical inquiry into the nature of photography as well as a eulogy to the author’s late mother. In Sunshine, Roe approaches multiple experiences of mourning and loss, informed by her personal experiences of the death of her father, as well as several other family members and close friends, through a visual response to a particular tree on top of a hill in Asheville, North Carolina—an earlier engagement with her considerations of the general and the specific in conveyance of grief.

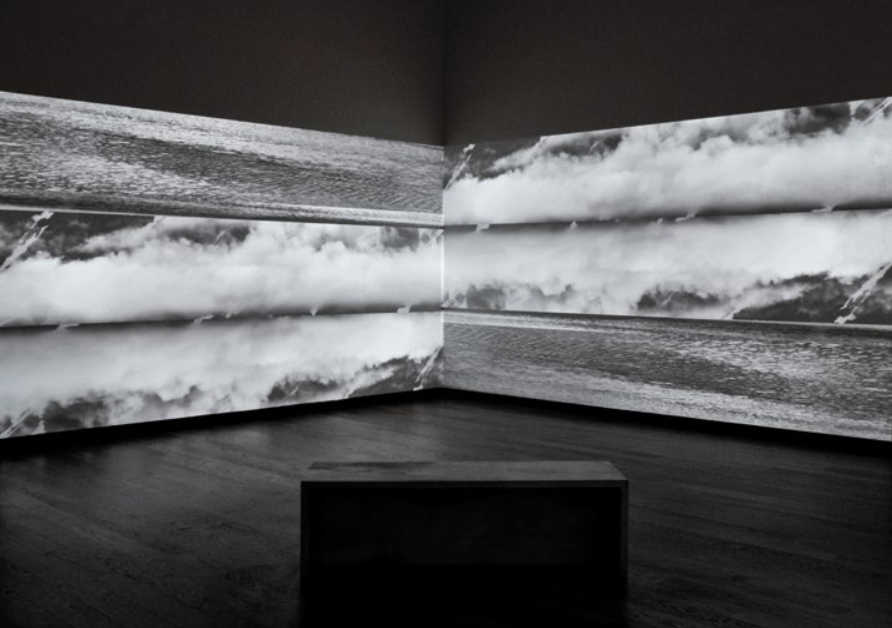

Mountainfield Study, (Installation View), Orlando Museum of Art, Orlando, FL, 2016 (Image courtesy of The Orlando Museum of Art)

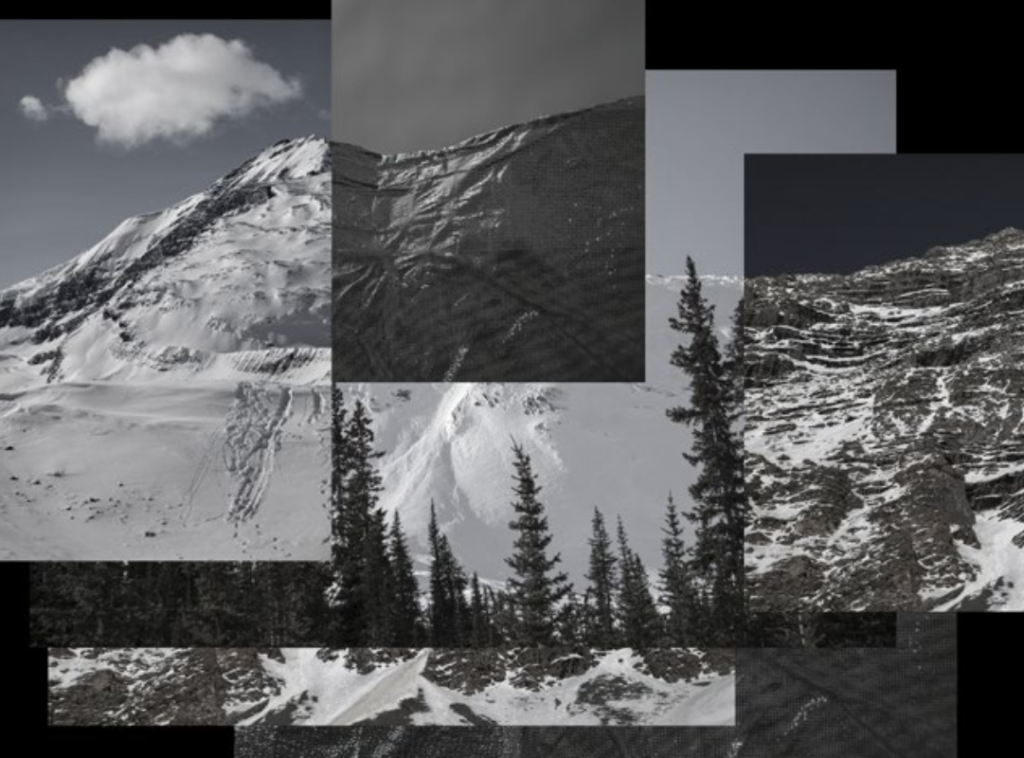

Mountainfield Study (Glacier, Rock, and Scrim), Pigment Print, 2016

Roe’s work exhibited in the 2016 Florida Prize in Contemporary Art show at the Orlando Museum of Art, Mountainfield Study, leaned further into her interest in exploring the camera as an optical tool which influences perception. Mountainfield Study was a split-projection, single-channel video installation comprised of photos and video collected during two artist residencies, one at the Banff Center for the Visual Arts in the Canadian Rockies, and the other at the Listhus Artist Residency Program in Iceland. The dizzying landscapes juxtaposed with occasional frames of random materials such as aluminum foil and fibrous cotton, caused the viewer to experience what Roe refers to as “incongruities”—subtle shifts in perception between what we sensorily experience in the world and what we experience in photographic depictions of such, calling attention to and subverting the illusion of reality frequently implied in photographic forms.

Mountainfield Study (Tree, Rock, and Ice), Pigment Print, 2016

In an earlier body of work, Goldfield Studies, Roe responded to the histories and physical landscape of the Bushlands of Australia while living there as the artist-in-residence at the Visual Arts Center of LaTrobe University. Roe created a series of paired and multiple photographs and digital videos, combining a documentary approach with constructed interventions into the landscape, concerned with “the discrepancies between space as experienced in the past, and as represented in the present,” pairing stillness and movement against a backdrop of a landscape steeped in disparate histories “constructed from the opposing perspectives of indigenous and colonial settler narratives, pastoral landscape representations, folklore and myth.”

The Sunshine Bores | The Daylights, HD Video Still, 2016

The Sunshine Bores | The Daylights, HD Video Still, 2016

Roe continues her explorations of loss, grief, mourning, and perceptual engagement with her experiments with branches of yew, in preparation for an upcoming artist residency in Spain, proximal to Portbou, the location of noted cultural critic and author of The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction Walter Benjamin’s 1940 suicide. Benjamin took his own life while attempting to escape from invading Nazi forces, after the French government ordered Spanish police to return refugees into Nazi hands. As we delve deeper into global crisis, war, and a swelling fascist sentiment, and as our executive branch remains hostile to human life, Benjamin’s death becomes increasingly relevant. Also relevant is an engagement with what we perceive as truth or reality, and how we are shaped by the technologies through which we see the world. According to political theorist Hannah Arendt, “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the dedicated communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction, true and false, no longer exists.” As we cease to critically examine what signs lead us to believe something is credible or truthful, we fall prey to the fabrications of opportunistic fascists.

The Sunshine Bores | The Daylights, HD Video Still, 2016

Roe is deeply affected by our current political situation. Grief is a proper response. As an artist who is engaged with perception, representation, and the porous and malleable nature of what humans accept as reality, Roe’s experiments with “incongruities” provide necessary critical engagement with our increasing ability to accept duplicitous realities from sources posing as truthful (with the photograph’s apparent verisimilitude as a starting point for this discussion). Her use of the historically and politically loaded form of the landscape, which she believes to be a space in flux, is also significant and relevant to the country’s mood of heightened nationalism and xenophobia. Walter Benjamin’s death was a result of a violent construction of geopolitical realities; false borders enforced with a very real and callous disrespect for human life. This is a death repeated many times over, and constantly doomed to be repeated again until we question the feverish and violent defense of constructed realities. Both grief and a criticality of “incongruities” experienced in factuality are places to begin.

You can see more at: DawnRoe.com