Maxwell Hartley is not of this world. He is a visitor from a parallel universe; one in which natural resources are cherished like gifts and are conserved and preserved. The humans in his universe reject the perpetual desire for more and for new and for the newer still—desires so rampant in this universe. In his universe, Hartley is a punk sage endowed with the understanding of how quickly a civilization crumbles under its obsession with superficial systems and ideologies. Knowing this, he is charged with the task of delivering humankind in this universe from its own demise—self-destruction via mass consumption. Assuming the guise of an artist, Hartley embarks on a seemingly impossible mission. It is a Logan’s Run-style odyssey to free humankind from its self-imposed shackles of consumerism before time expires. In thirty short years, he has accomplished so much, but there is more to do.

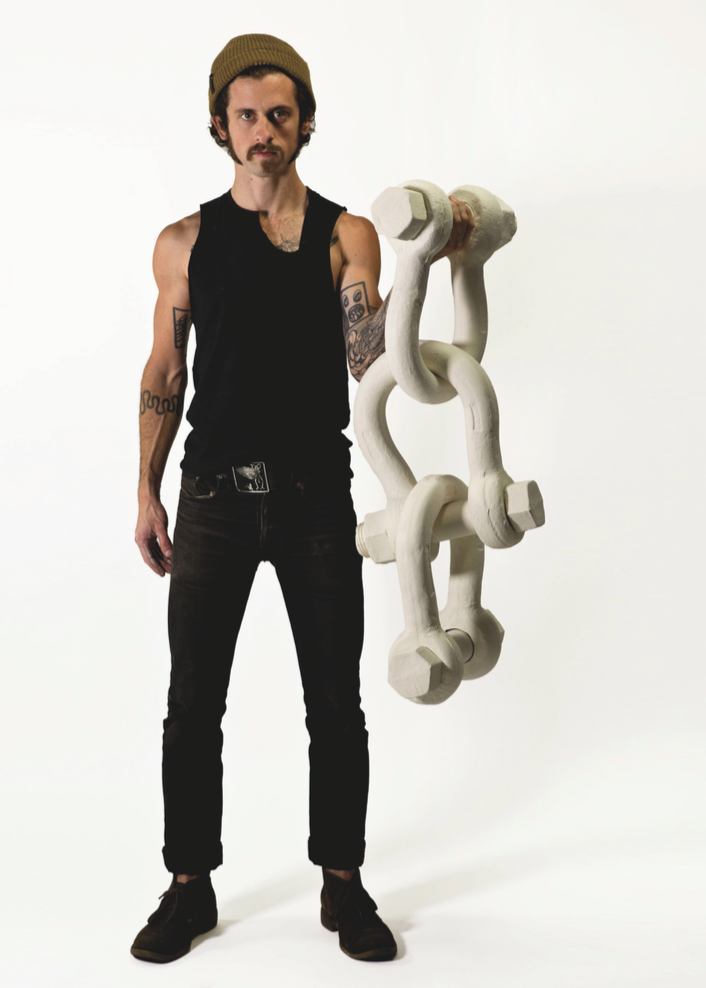

Anomaly, cast ceramic, photo by Shelley Lake

The humans in this universe live disposable lives and Hartley’s gift (and curse) is the ability to see below the surface of everything. Everything. His work begs the viewer to seek a life of substance and to abandon the need for instant-gratification. His artwork encourages the viewer to relinquish a life spent floating on the surface and to sink like an anchor into a world of meaning, emotion, and purpose. His work continually suggests that feeling the pressure and darkness and uncertainty of the deep oceans of life are necessary to human existence.

Anomaly, cast ceramic, photo by Shelley Lake

The success of Maxwell Hartley’s work is that it connects with the viewer on a subliminal level. What, at first, appears to be simply a found-object sculpture is, in actuality, a desperate plea to abstain from the disposable nature of a mass-produced society. His epic sculptures, using industrial materials like steel brackets, epoxy, urethane, and wooden joists, instruct the viewer to build his or her own life with structural integrity. His handcrafted guitars are axes arming humanity with majestic musical weapons with which to combat consumerism.

Hartley’s found-object sculptures are the key to understanding his plight. His use of non-art items and thrift store treasures is so subtly serene that the viewer does not realize he or she is seeing something wholly new and profound. His assemblages are not intended to shock the viewer in the way the Dadaists used taxidermy and urinals. Instead, Hartley becomes a didact of the discarded and asks the viewer, “What makes something worth keeping around for a while different than that which falls to the wayside to crumble?”

Hail Mary Full of Grease, mixed media installation

In the 2013 sculpture Hail Mary Full of Grease, one of his found objects is a replica of a Virgin Mary statue from the Christian religious tradition. The original statue was “borrowed” from a neighbor’s yard and returned after a mold had been made. The new statue has the Virgin cast in ebony porcelain, sitting atop a weathered, vintage milk jug. A mechanism inside the milk jug allows for water to flow over the Virgin, creating a never-ending font of renewal. This is not just “art as commentary” on humankind’s addiction to the disposable. This is art with a message. Hail Mary Full of Grease reminds the viewer that just because an object is discarded, it does not necessarily mean it disintegrates. Materials from nature may biodegrade over time, but materials created by humans are not as quick to decay. Landfills are tombs filled with the expendable. Hartley’s use of the Virgin Mary symbol, combined with the flowing water mechanism, conveys a sense of eternity, spiritual or otherwise. Indeed, it suggests that all things, humans and objects, live forever.

Dark Matter Sewing Box, vintage sewing box, laurel oak burl, cast epoxy

Dark Matter Sewing Box, a piece from 2015, is another example of Harley’s exceptional found-object art. This piece, deceptively small at 16 inches in height, literally carries the weight of not just the world, but of entire galaxies. Behind the door of a vintage sewing box, the viewer discovers an orb, created by filling a balloon with black epoxy. This balloon, intended to hold helium or air, is now filled to near explosion with a dark and heavy mass. Once the epoxy has dried, the balloon is cut away. However, the new object retains some of the balloon’s characteristics. Like the balloon, the newly created orb seems close to exploding at any minute, yet it is permanently frozen in time, unable to deflate or to expand further. This contradiction of a balloon that cannot and will not explode, resides within the confines of a decorative box and is wrapped with a wooden burl. The discarded piece of oak that encircles the orb seems to prevent it from escaping its cell. Despite its static nature, there is an air of movement about this piece. The orb desires expansion and escape, but the oak burl will not allow it. There is so much activity, so much struggle taking place behind the closed doors of this sewing box. It is the same for humankind, as the struggle to be free is so often hidden behind intricately decorated locked doors.

Installation shot at Art Basel Miami Beach, 2016 in the Spectrum tent

Maxwell Hartley’s impressive sculpture work with discarded industrial materials is the loud, prophetic cousin to his found object pieces. If Hail Mary Full of Grease is the humble nun working tirelessly to improve her community in small, quiet ways, then Hartley’s 2008 piece, Vessel, is the boisterous street evangelist proclaiming “The end is near!” Hartley, the visitor, the sage, and the artist, recognizes that both methods are required to reach humankind and affect change: the striking, large-scale, “loud” pieces and the subtle, understated, “quiet” pieces.

Vessel, wood, steel, paint, cast urethane foam, photo by Steven Alvarez

Vessel is that loud piece, one the viewer cannot and must not avoid. Despite utilizing traditionally industrial materials, it is a surprisingly human piece. The use of life-size human figures cast in urethane foam is deliberate and powerful. Vessel is a sculpture that holds each viewer accountable and undeniably screams, “This is about you! This is about all of us!”

In his book, In Abandon, Hartley explains that “We are a species predominantly occupied with movement. We have helped our planet evolve into a system ideally suited to distribute specific bundles of matter about its surface for consumption.” Vessel forces the viewer to question his or her role in this system of consumption. Are the human figures gears in the mechanism of “progress,” moving the system along and creating more things to consume? Or are the figures trapped inside the consumption machine, prisoners desperately trying to escape a system of their own creation?

Capsule, oak, steel, India Ink, sculpture

Hartley reaches out to humankind via his artwork, both the loud and the quiet pieces working together to warn against the pitfalls of the superficial. But he does not visit this universe only to deliver a message of warning. He is here to provide humanity with the proper weapons to fight back against the foes of superficiality and consumerism. His weapon of choice is the guitar. It should come as no surprise that Maxwell Hartley ventured into the world of instrument creation or that he chose to create guitars above all else. For centuries, humanity has used music as a way of passing down ancestral history, telling stories, conveying profound truths, and expressing emotional turmoil. Court jesters used humorous songs to jovially roast their employers and Shakespeare often included songs in his plays. Hartley continues this human tradition in the 21st century, not by creating the music, but by creating the object that makes the music.

Zeebass, Florida cherry wood, photo by Jason Ruznock

2016’s Zeebass is a powerful machine, an instrument of precision and elegance. For Hartley, “building a guitar can be seen as a form of ultimate sculpture.” Creating a musical instrument with the intention of using it to make music is not simply assembling the correct parts in the proper order. It is more like crafting an exquisitely dangerous katana for a samurai. Hartley elaborates on his artistic intent by stating, “These works challenge the viewer to consider the potential energy bound within common elements.” By focusing solely on the instrument itself, Hartley is essentially equipping musicians with a piece of artwork on which they can create their own art. Bulletproof Dimebag is a glorious example of all the pieces coming together, culminating in a guitar that is both shocking and perfectly self-evident at the same time. Built in 2016, and made entirely of material found from a discarded bank teller window, Bulletproof Dimebag surely makes the musician playing it feel indestructible.

This is exactly why Maxwell Hartley is here in this universe. He builds guitars and creates artwork not because it is easy, but because it is hard. He is the JFK of sculpture and he is here to prepare, arm, and lead humankind into the battle for its own soul. Hartley is well aware of his purpose and mission, explaining that, “People need [a] constant reminder never to lose the ability to appreciate the sublime beauty of primitive nature; that the grandest of all journeys and studies are still within our grasp and give purpose to our imagination.”

Bulletproof Dimebag, reclaimed bank teller window, hardware, Shelley Lake

Maxwell Hartley has seen the future. He has seen humanity’s demise in this universe from a far-off place. His universe is one of hope and connectivity and creativity. Humans there are heavy and deep and care not for superficial things. They are creators, not consumers. They delight in giving old objects a new life because they understand that all things are eternal. This is what Hartley brings to this universe through his artwork. Maxwell Hartley is an artist, a sage, and a visitor from another world, and he is most welcome.

You can see more at: MaxwellHartley.com

his travels landed him with good people….. Glad he has stayed this long. We are blessed. , frankie

Awesome, awesome article. Just what I needed.