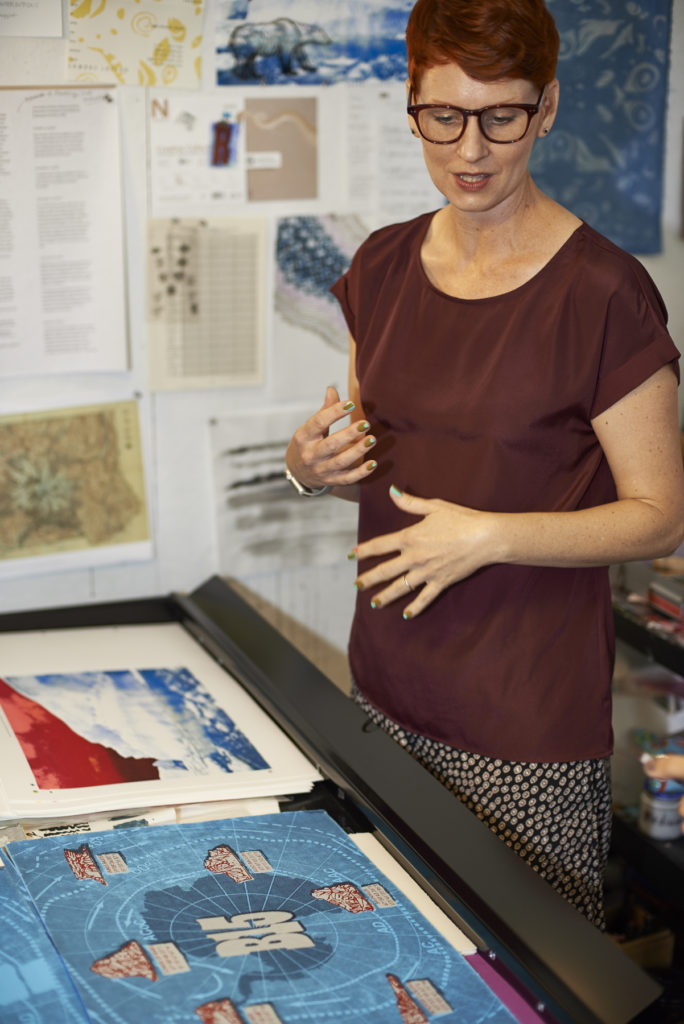

What is the reality of climate change? What are ways to invoke or even evoke a dialog that is both important and easy to digest? How do we bring these serious issues that seem almost impossible to fix to an audience’s action-orientated attention? Rachel Simmons, artist-educator and Professor (at Rollins College) sees “visual art as the ideal vehicle to express the tensions between politics, culture and sustainability.”

I do feel like the artist is in direct contact with a very large audience. The audience gets to critique and form an opinion on the work. You can’t really critique and talk about the sciences in this way unless you’re studying science.

I sat down in an interview and studio visit with Simmons to talk about ecotourism, her Antartica series and the inner dialog of choice. We get into her creative process and the ways she formulates ideas to create new works. She creates art with a sense of self-awareness of harm to the environment in mind. Simmons wants to remind the audience, and herself, of the choices that we make in our everyday lives and how, maybe, the seemingly small things we do out of convenience can be changed to help the environment on a global level.

Did you grow up in Orlando?

I ended up in Orlando for college where I went to Rollins as an undergrad. Then I went to Louisiana State for grad school and then ended up back here at Rollins.

What did you study?

I was in the honors program here, which is a unique interdisciplinary program where we look thematically at global issues and then tackle them from multiple disciplines. For example, if we wanted to discuss the way the human brain functions, we would study that through psychology text, neuropsychology text, spiritual text, and anthropological text—then we’d get at the human brain from all of those different angles.

Were you always interested in environmental studies and climate change, or did that interest spark after grad school?

I think that my environmental awareness didn’t really develop until during the Iraq War. It was right around the time my husband and I decided to start a family, and we were thinking, What is it like to start a family when your country’s at war? So, this was pretty much right after 9/11. There were a lot of these new environmental movies coming out like, An Inconvenient Truth—and then Leonardo DiCaprio did a big blockbuster environmental film, The 11th Hour. That environmental discussion was happening in the public. We were also shifting from using this term “global warming” to “climate change.” So, I started to become interested in the discussion around how we were talking about it and why we were talking about it. At the same time, I had these opportunities at Rollins to travel. I didn’t grow up with much money, so there wasn’t a lot of traveling in my younger years. Maybe traveling within the country, but not internationally.

Like to Antarctica?

Right! When I had those opportunities, I started to travel specifically to places where ecotourism was, in some way, shaping their economy.

Define ecotourism. I need the audience to know the exact definition because I honestly had to look it up.

Oh, yeah! That would be, if you’re trying to develop some tourism in your area, and you want to pull people in because of the natural beauty of your area. The Grand Canyon is an example of ecotourism. Like national parks, where you go to see nature—you’re not going to New York City to see The Met. You’re going just to see the wilderness, or this idea of the wilderness. There’s this whole industry that’s grown around that. There are all kinds of ecotourism. There are coffee plants in Costa Rica where you can go and live for free as long as you work on the plantation. You can go on a luxury cruise and circumnavigate Antarctica. Those are two very different ends of ecotourism.

So there’s a spectrum?

There is a huge spectrum in the ways you can engage as an ecotourist. There are ethical dimensions to how you go about doing it and whether or not you’re leaving a huge carbon footprint. I’m not interested in judging if ecotourists are thinking about these things or not; I’m interested in the idea of us thinking about that as we travel. It’s a little ironic going to a place that’s ecologically sensitive.

After looking at the didactic writing you have up on your site, I realized that there are elements of self-awareness in the Antarctica series. I initially read them as this type of activism where you’re critiquing society and excluding yourself, but what you’re actually doing is including yourself in the critique and the issues.

Yeah! We’re all included because we can’t escape it, really. Unless you’re going to go and live off the grid. We live in this system. I live in Orlando, I can’t not have a car. I could, but that would be a very purposeful choice for me. I’d be lucky enough to make it a purposeful choice and then I’d have to really work hard to make it happen in my life without one. So, there are certain systems in place that I can’t change as an individual. I can be aware of them and make a choice of what I do within that system, but I can’t completely escape the system.

Wow… 100% Agreed.

[Laughs] That’s sort of where the tension is! Which I think is interesting.

Yeah, I love the internal dialog that you kind of have to have with yourself like, with what you choose to eat. “How bad is this for the planet?”

Absolutely! Every choice we seem to make—everything we are going to consume is political and cultural, which is exhausting, but you know…

Orlando is very interested in food. Asking if things are local is super trendy. It’s great; I wasn’t really asking myself these questions five years ago.

It is very trendy. Let’s see how long it’s trendy for [laughs].

Have you seen the Soylent stuff?

Yeah, it’s hideous, and he (Rob Rhinehart) named it after Soylent Green, which is a sci-fi movie about eating people.

I’m kind of into that. I like the packaging. It’s very mundane. It’s black and white and just gets to the point.

It’s very futuristic.

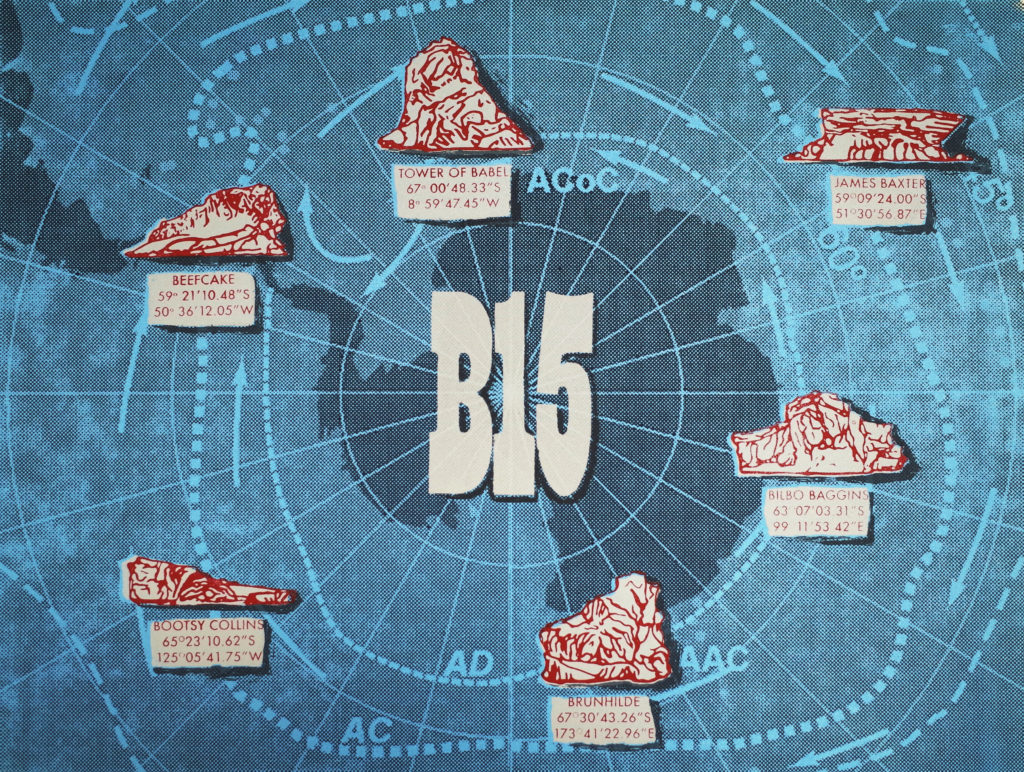

With your trip to Antarctica and the images you created afterward in the Antarctica series, there are these monochromatic blue tones that are almost interrupted by the color red. Can you explain why you made these choices?

That’s actually from going to and experiencing Antarctica. There’s very little variation in color in the landscape except for the sky, but then when you run into the scientific bases, they’re all painted orange or red so you can see them. In a storm, you would need to be able to spot them, so they’re all so bright. That’s why I starting using those colors—to describe things in these images.

Were you always into printmaking or was that a recent choice?

I studied under a printmaker named Tanja Softic. She now teaches at the University of Virginia in Richmond. I took a lot of printmaking as an undergraduate; she was very influential. I did lithography, letterpress, relief, monotype, etchings, and just tons of different printmaking. I didn’t apply to printmaking for graduate school because there were only a certain amount of spots that were open. Painting and drawing always had tons of spots, so I sort of hedged my bets and just went into painting and drawing instead. Which really worked out, because that was a whole other skill set that I had. When I came back and applied for this job [at Rollins] I had to teach half of the studio curriculum—from figure drawing to basically everything. Everything except for graphic design and photography. If I didn’t make that decision, I wouldn’t have been able to do all of that. I’ve been teaching the printmaking course here since 2008. We’ve changed a lot of our equipment; most of it is environmentally friendly.

What processes are safer?

Water-based, mostly; all of the screen printing that we do here is water based. With things like etching, you have to use acid baths and there are fumes. There is a whole new movement within printmaking to make it greener.

How new?

I want to say within the last 15 years, people have really started to focus on it because a lot of printmakers are exposed to a lot of toxic stuff for decades.

With printmaking, do you think it is easier to create textual work, because you aren’t really focusing on creating these perfect forms, but maybe just choosing the right word/language to use?

I did a lot of writing back when I was a student here. I actually did my thesis on the relationship between text and image, because I always found it very fascinating. Anything I saw where text was the image was just always very compelling to me. As an artist and writer, I have incorporated text a lot within my work. I also have access to all of this equipment here as a professor. It’s always encouraging me. I’m an artist who likes a lot of other stuff, not just art. I’m into environmental science, comics, and fiction. I’ve always been interested in little science guides on how to identify rocks and lizards, etc.—any kind of science material really. I draw from these things as influences as much as I would an exhibition.

I watched your 2010 Green Art Ted Talk and you mentioned reading Cabinet of Curiosities by Albertus Seba.

That book is right there behind you! I think as a textual artist and a printmaker, books are like raw material for me. Especially with books like that, they’re really historical and they represent this fusion between art and science. Art needs science and science needs art. Science needs art a lot. Scientists aren’t good at capturing our imagination without visualizations. The artists who did the illustrations in Cabinet of Curiosities had to reanimate all of these dead specimens. So, these forms that the snakes are taking in the book are not actually happening. They’re the artist’s interpretation of these dead, stuffed creatures. So, their imagination really makes all of these images come to life. Naturalists, I think, have been always instrumental in bridging the gap between science and art. These are people who like to draw; they’re really careful observers of the natural world.

You’d have to be truly interested in these things because most of the language used in science isn’t really accessible or used anywhere else.

Yeah! Absolutely. Darwin is a good example of a scientist who was also a naturalist. He was recording, drawing, and cataloging everything that he collected, saw, and came across. His theory of evolution was written years after he saw the evidence for it. He had to collect, draw, and think about it, and let it simmer, and then this theory came out of all of that observation—but it was just observation. He had to document and reflect. He had to have been such a keen observer.

Are you currently reading/pulling from anything?

I just finished this graphic novel, Patience by Daniel Clowes. All summer long, I’ve been reading books about text, Letter by Letter by Laurent Pflughaupt; then Kern by Derek Beaulieu. I took a visual poetry class and the teacher had us read these.

VISUAL POETRY?! Have you read Jpod by Douglas Coupland? He uses text in this way! Visually?

Yes. I remember reading him in the 80s! The designs were super cool and he would write about yuppies [laughs]. This summer, I categorized all of the typeface that we have here, so I have all of these books about fonts and typeface.

I’m so basic…I am going to have to say my favorite font is Helvetica (I am transcribing this interview in Helvetica Neue).

Helvetica is a good one! There are those truly awful fonts like Comic Sans and Papyrus. Fonts are very interesting in terms of their history. A lot of the typefaces that we have on our laptops are all coming from the designers who’ve created the type for this process (letterpress).

I have a friend who has his phone in Comic sans, it’s the worst thing…

[Laughs] Oh no…if you really want to be a font snob, you should read Just My Type by Simon Garfield. It has such great stories about type. Like the guy who designed Baskerville, when he and his business partner split up, he didn’t want his partner to have the drawers of metal, the original cast type, so he ended up dumping them into the river so no one could have them.

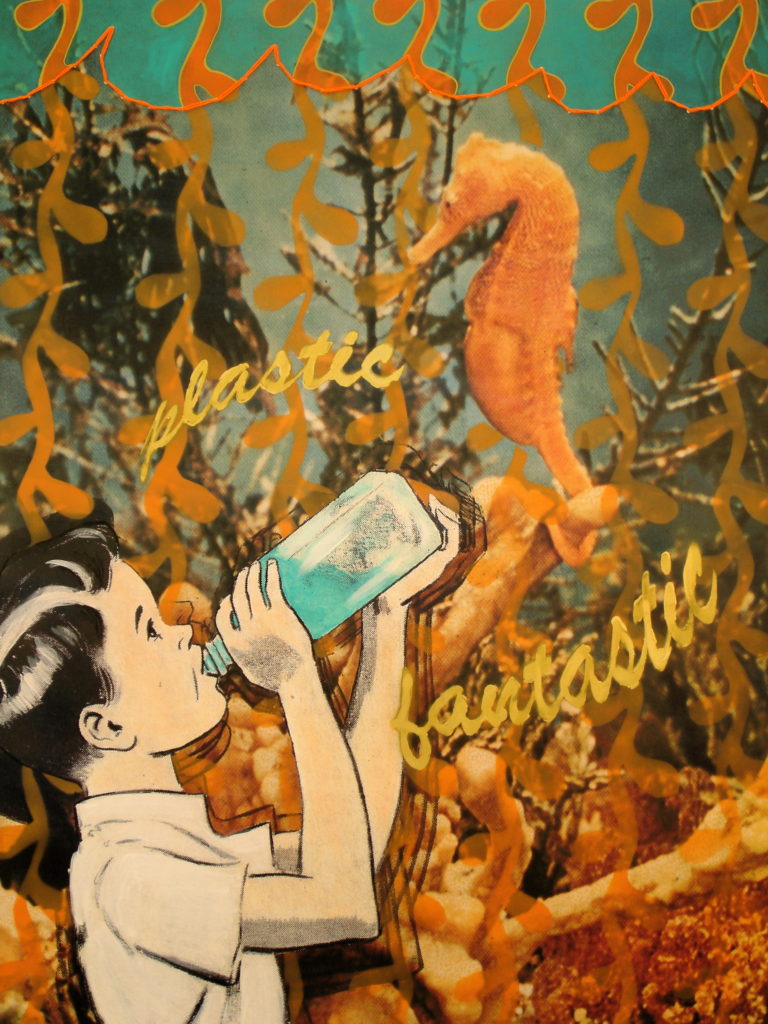

You created an installation, Wonders of the Sea, consisting of around 100 illustrations for a solo exhibition at The Cornell Museum back in 2007.

That project came out of a couple of residencies that I did. I did a residency in Hawaii. I ended up going down to the beach one day and finding all of this crap washed up on the beach, and started this investigation of how and why that stuff ended up there. If you’re from Florida you know our beaches are very clean because every inch of the land is owned by someone who’s responsible for cleaning it up. In Hawaii, it’s not this way, if no one owns it, nobody cares. It’s very rural. I started making work about pollution in the ocean and that’s where that body of work came out of. It was about investigating the diversity of the ocean. I was also thinking about building relationships with natural forms and with nature. The way that I build relationships is that I find some connection to them and then I start researching them, and then I visually make images of them.

The connection with natural forms and nature, is it about your presence in these spaces/with these things?

It usually is from an experience I’ve had. I went on a trip to the Galapagos Islands and every time that I take these trips, I’m usually with a bunch of people from Rollins—people who have PhDs—and they’ll fill me in on all of this stuff that’s happening over dinner or whatever. We end up talking a lot about these big issues like climate change or marine pollution, and we’ll talk about them from our different disciplines. It’s like a continuing education. I’m interested in seeing the world this way. I think that’s how the world works. We’re never going to solve climate change with just one set of people who know just this exact set of information in their field. We have to have politicians, economists, citizens, environmentalists, and soccer moms. We have to collectively use all of the knowledge that we all have and start to see things from the different perspectives. There’s not going to be this one solution or one person who comes up with that solution.

All of these different people do convey ideas very differently. The language used by, for example, an economist, would probably only reach a very specific audience.

Yeah! I’ve done projects with physicists where we’ll talk around and around something and we’ll be talking about the same thing, but we just use really different languages to speak about the same subject! There’s not a huge difference between what I do in my studio and what an experimentalist does in their lab. The difference is the outcome and the audience we’re intending.

You can see more at: RachelSimmons.net