Visceral is a word used almost too often in discussions about art—especially since it is meant to describe sensations devoid of visual/sensory input—but when an image hits you in your gut in the most innate, ornate, and grotesque ways imaginable, it seems like an understatement.

In New York-born photographer Roger Ballen’s work, there is a subliminal understanding that transcends consciousness and perceived reality—essentially; the right hook to your gut that took you by surprise during a pleasant gallery visit. At Snap! Space, the gallery organized a retrospective collection of Ballen’s dark, sometimes theatrical renditions of the conscious and subconscious mind in a fluid trajectory of his career.

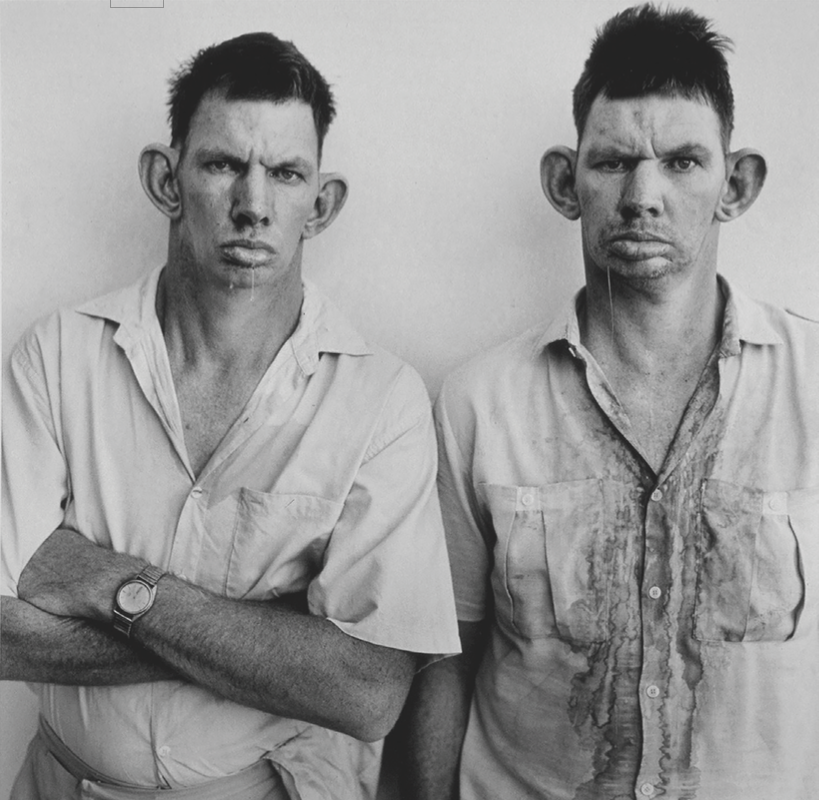

Dresie and Casie, twins, Western Transvaal (Platteland series)

The collection includes earlier pieces from his series Outland to his most well-known photographs taken of South Africa’s politically privileged white minority in Platteland. Ballen has lived and worked in South Africa since the 1980s, where he initially worked as a geologist. The move prompted him to continue his photographic hobby as a full-time career and his portraits of Afrikaners in rural South Africa have been compared to iconic photographers like Diane Arbus (his portrait of two South African twins especially resonated with Arbus fans, and it is one of the most recognizable images in contemporary photography).

Arbus comparisons notwithstanding, Ballen identifies more with playwright Samuel Beckett. The starkness of Beckett’s plays, the dirty furniture, dismal characters, and bleak backdrops are logical comparisons to Ballen’s pieces, as his work has become gradually more psychological than social or economic. Actually, they’re all of these things. They’re a contemplation of the inner recesses of the mind in relation to the gruesome nature of the impoverished, the rural, and the marginalized; in summary, the kind of gruesomeness we try to avoid in our polished lives.

Why do we find these images disturbing, beguiling, or strangely humorous? Do we turn our heads before the hypnosis of Ballen’s strange world sucks us in? For a photograph to be Ballenesque, it must be penetrative. It has to hold us under a spell. It leads us to consider the grotesque, perverse dimensions of our reality—whatever reality may mean to us. Some may argue that art is a reflection of the viewer; that a photograph can act as a mirror. The images may reflect something unsettling, ugly, or deeply revealing about us.

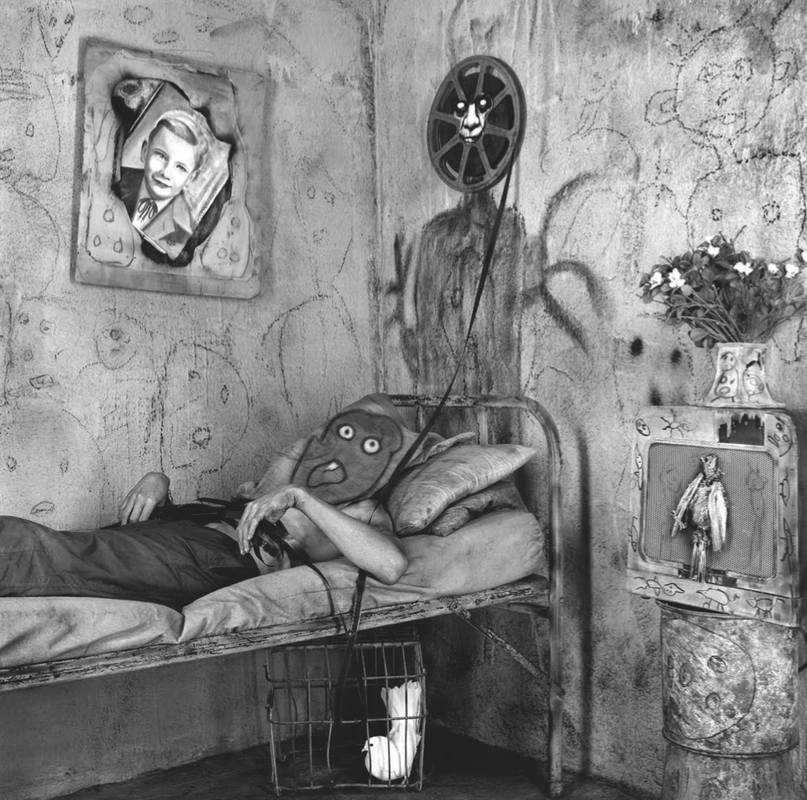

Eugene on the Phone (Outland series)

His work is fascinating because it forces us to do all the mental work, facing the primitive machinations of the mind. At first glance, his work doesn’t seem to be a stripping of the viewer, but it can disarm us. Like the mirror in a gritty public restroom, Ballen’s work forces us to look at the sloppy wall art, the stained furniture, and the grimacing people. Perhaps the scenes look all too familiar in their perverseness, revealing parts of ourselves we believe to have safely tucked away, like in Unwind, a piece in the Asylum of the Birds series, showing a man lying on a meager bed frame. His face is covered by a menacing doodle drawn on fabric. It’s eerily frightening to imagine what lies underneath.

This is one of most impressive things about Ballen’s photographs: each one embodies the underbelly of human consciousness in a millisecond of reality exquisitely assembled and captured. Ballen’s structures of the subconscious are concrete manifestations of the psyche. The Theatre of Apparition was partly inspired by drawings and carvings found in an abandoned women’s prison, and a suburban home is the setting for Asylum of the Birds, leading us to the temporal in-between captured in Boarding House. In the darkest depths of existence exposed in Shadow Chamber, a three-story building with literal chambers of animals, humans, and objects interact, incorporating sculptural and formative motifs more than any other Ballen series. There is a textured assortment of people and animals that leaves viewers feeling a sense of abandonment. The subjects are petrified, frozen not just by the artist’s immortalization of them through the photographic form, but also by their environment.

It was around 2000 when Ballen began to incorporate portraiture and drawing into his photographs. In Eugene on the Phone, a boy lies in a classical pose on a stained couch, holding a frantic cat by its tail while holding a telephone receiver up to his face. The form of the cat, the young man, and the crooked stenciled silhouette of a hanger on the wall somehow join harmoniously.

Unwind (Asylum of the Birds series)

Looking at the retrospective, it’s easy to pinpoint Ballen’s other repeating motifs: heads and limbs arranged to give off both a sense of disembodiment and tangibility, along with birds, wall drawings, protruding wires, and emaciated figures, but the explication of his work sounds messier than it looks. Beyond the Jungian undertones of the shadowed self, the compositional components of Ballen’s work are striking in their clarity. Some may call it organized madness, a reflection of the transferable nature of inner chaos. One of the most impressive things about Ballen’s photographs is that each one captures a glimmer, a millisecond of reality, in the most ironically well-assembled manner. Each piece is rich in its fullness and so that viewers can diagram his work from over the years, which is why the organization of the exhibition functions well for both those familiar with Ballen and those exposed to his photographs for the first time.

If you are the latter party, you may wonder about the ethics behind the work. Is he exploitative of people who may be physically and/or mentally disabled? Is it acceptable to capitalize on this otherness, this ambiguity, derangement and isolation shaped into oddly slapstick and absurdist forms? Ballen emphasizes that he isn’t ridiculing or manipulating the people he’s photographing, but that doesn’t stop us from considering the relationship between people and props within his work, or the subject/object dichotomy in photography. Ballen gets to know these people—a strategy many contemporary photographers use, but few plunge into as intimately as he does.

Since the subjects of these photographs are mainly the economically disenfranchised—white social outcasts of apartheid—his work can be problematic. It can lead viewers to believe he is detracting from the complexity of modern race relations in South Africa. Are we indulging in this problematic and disturbing voyeurism like visitors of a carnival freak show, half scared, half enthralled? Either way, Ballen does more than hold us in a momentary grip; he imprints us with his work and reintroduces us to our shadow selves.

Roger Ballen – In Retrospect, a 30 year retrospective of Roger Ballen’s work, is on view at Snap! Space, until December 17.

You can see more at: SnapOrlando.com