Why don’t we begin the evening with one big collective scream?”

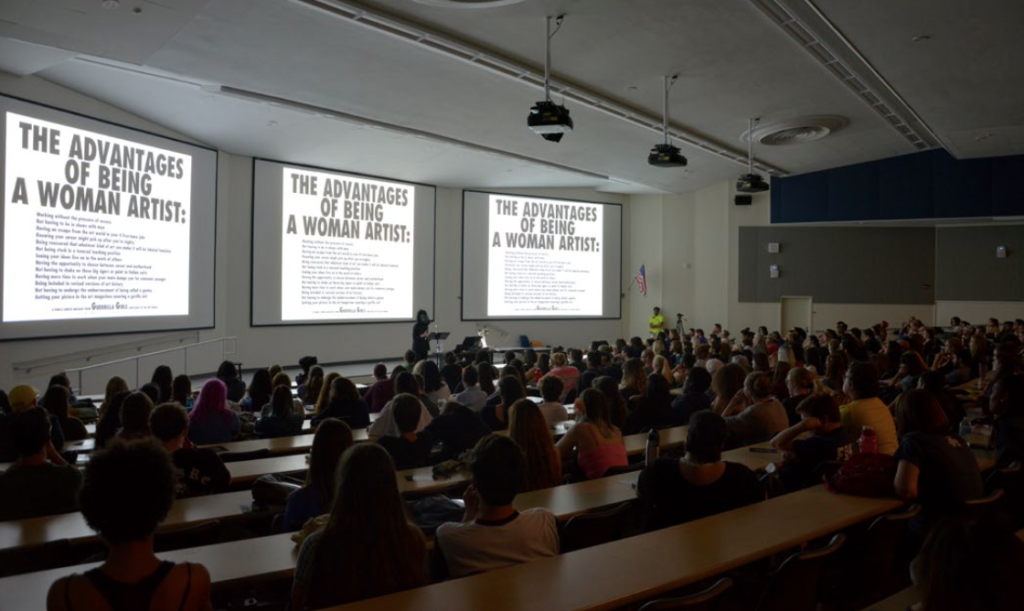

Moments later, the Carleton Auditorium at the University of Florida erupted into a jarring choir of the cries of those feeling the heaviness of our social and political climate. I would be lying if I said the reverberation of my scream beating against others didn’t feel amazing; it was just the release I needed. The question was prompted by Guerrilla Girl Frida Kahlo, who visited UF on February 14. While couples across the globe were celebrating Valentine’s Day, hundreds of people from the Gainesville community gathered for the best date of all: a conversation with a Guerrilla Girl.

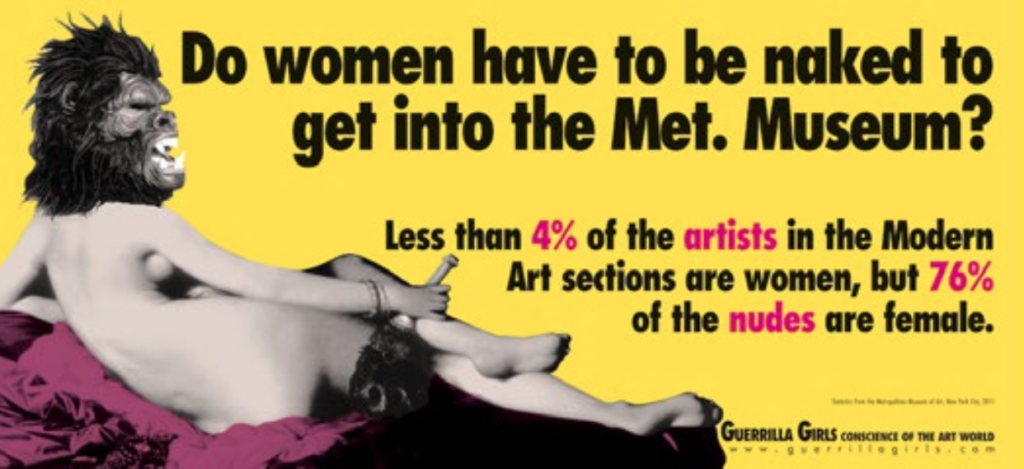

It’s been 30 years since the infamous gorilla mask-wearing, social-activist feminist group called the Guerrilla Girls tilted the art world on its axis. In 1989, they brought to light the shocking statistic that, “Less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female” within the walls of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and prompted the question, “Do Women Have to be Naked to Get in the Met Museum?”

The Guerrilla Girls are superhero vigilantes of the art world. They act anonymously, assuming the names of dead women artists and utilizing a hybrid of fact-driven data and humor to demonstrate the obvious underrepresentation of women artists and artists of color within the scholarship and exhibition of art history. In some respects, things have gotten better; to cite one specific example, the optimistic feminist inside me immediately applauds the appointment of Christine Macel as curator of the 57th Venice Biennale as a hallmark win for the progressive advancement of the art world. Although slight glimmers of equal representation are becoming more present, overall, there is still much work to be done. In 2012, the Guerrilla Girls revisited their original question, “Do Women Have to Get Naked to be in the Met Museum?” only to find that less than 4% of the artists in the museum were women, but 76% of the nudes were female. Are these numbers discouraging? Yes, absolutely. But the fight is far from over.

More than three decades later, the Guerrilla Girls are still fighting for the “radical” notion that women artists and artists of color are just as significant, if not more so, than their white comrades. Dubbing themselves the, “Conscience of the Art World,” they relentless protest the inequities that exist within museums and the art market.

“Art and art history should look like who we are,” said Kahlo, delving into the ways our largest public art museums—meaning cultural nonprofits that receive federal funding from our tax dollars and exist for the good of the public—are systemically controlled by the 1%. Public museums are just that—public—and the collections they store and exhibit should be a reflection of the communities they represent. No longer does it seems rational for a museum located in the heart of a minority-majority city, such as the Met in New York City, to present exhibitions where over 80% of the artists are white males. Where is the art that reflects values my friends and I relate to? Where are the artists who truly represent the American experience? Where’s the diversity?

To cut museums some slack, there are many public institutions today that do house diverse collections and actively seek to exhibit women artists and artists of color, largely to the credit of the Guerrilla Girls’ activism. Almost ironically, many major museums that the Guerrilla Girls have protested now collect their work. The Whitney, for example, is now a proud collector of the very fact-driven posters used to espouse the lack of equal representation of artists within that institution’s collection.

“We embraced it, it opened us up to new audiences,” said Kahlo, noting, “It’s kind of fun to protest these museums right on their walls.” The Guerrilla Girls are inherently educational in their purpose, just as museums are educational in their mission. Understanding the potential impact their posters could have to enlighten museum visitors, the Guerrilla Girls now reproduce full portfolios of their seminal work, making a large breadth of their posters available to collectors. Having their work collected by museums has proven to be a successful tactic, furthering their quest to expose the gender and ethnic bias that exists in the art world and society at large, by placing themselves within the timeline of Western art history.

However, Kahlo was quick to explain, “We’re not scholars, we’re popularizers,” and emphasized the importance of working collaboratively to support a cause. The Guerrilla Girls are not about high-brow, esoteric work. They let facts speak for themselves, adding a punchline or outrageously funny quip to entice viewers. “If you can make someone who disagrees with you laugh, you sort of have a hook with them,” she posited.

Toward the end of her talk, Kahlo highlighted the importance of staying aware, of asking questions, and of getting vocal about societal issues that demand more critical attention by the populace. She spoke of the power in being “a professional complainer,” reclaiming the word “complain” in a way that makes it a positive method for creating change.

So when Kahlo commanded the entire auditorium to scream, her intention became deeper than just having us produce sound. It was a call to action that rippled through the entire auditorium, our cries became promises to one another to become more active and engaged citizens. By inviting us to “make trouble together,” she encouraged the audience to join the Guerrilla Girls and their impressive history of activism to demand equality in our society. Kahlo’s visit to UF truly planted the seeds to inspire a new generation of activists in our own community.

Photos provided by the Casey Wooster, University of Florida, College of Arts

To learn more, visit: http://www.guerrillagirls.com/