Central Florida is, at once, a draw for all manner of peoples from all corners of the globe, a melting pot of culture, and a grey, muddied mush pressed into the pungent forms of souvenirs, repainted and sold to any passer-through. It’s not just the kitschy roadside shops, either; any Walmart or Target or CVS or Publix within a 50-mile radius of the beaches or the theme parks will have a section devoted to towels and sand pails, to Mickey Mouse and to orange groves.

But there is a current of the macabre in our entire regional identity. It is this siren’s call, drawing outsiders in to Circe’s temple, enchanting even the most intrepid and jaded to stay for days, weeks, months, and years at a time until forever and ever (our tourist culture is one that reproduces by inhabiting our visitors with our spirit, not unlike tachinidae flies). Orlandoans repose in Homeric poeticism, but from the highway we can’t be seen “lolling there in their meadow, round them heaps of corpses rotting away, rags of skin shriveling on their bones.” That’s the crux of our local culture, the part that’s for just for us.

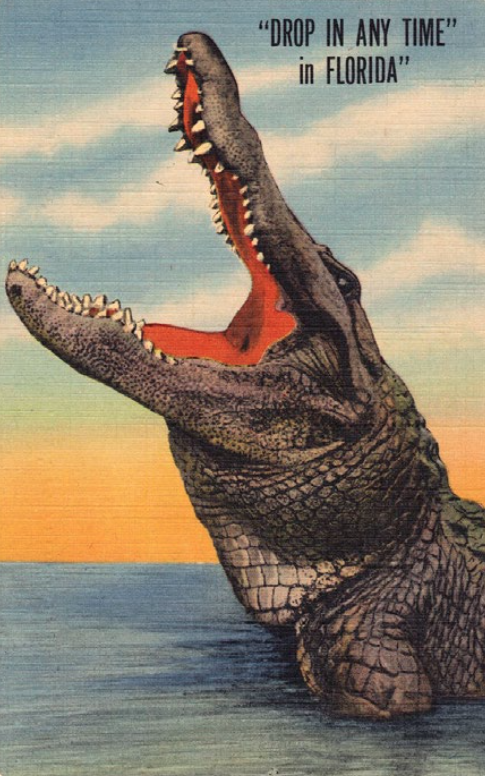

Legendary are our monstrous beasts: giant alligators that eat other alligators in plain view along the suburban foot paths, invasive exotics that have super-evolved in the temperate scrub forests, man-hungry monsters with running kill counts put on display in local zoos that double as alcoholic oases, even our very own iteration of Bigfoot—the Skunk Ape—is suspected to live unseen and unhampered by human interference in the shrinking Florida wilderness.

The “Florida Man” headlines are iconic. These madlib jumbles could only ever feasibly happen in this land of gods and monsters. (“Florida Man tasered in eye at One Eyed Jack’s in Orlando” makes a classic example.) Headlines are always received humorously despite almost always being tragic, and entire online fan cults of Floridians and non-Floridians surround the Florida Man phenomenon.

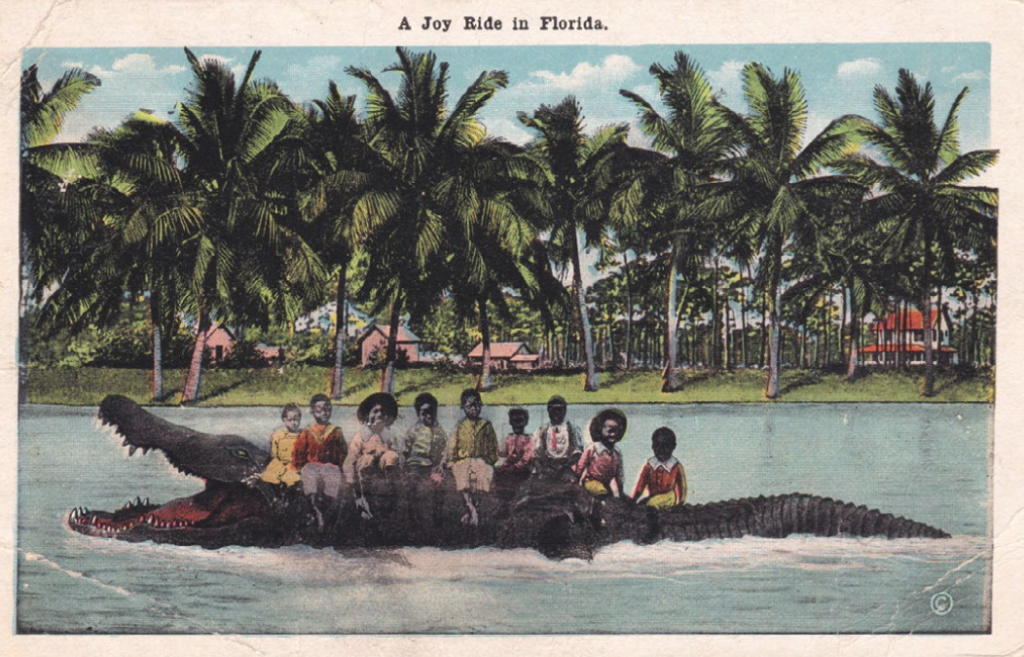

Here, ecological landscapes and cultural scenes intermingle, shift, nudge borders, and threaten to consume one another for once and for all. We know the beauty and the artifice of Central Florida rests on the shoulders of capitalist deceit and violence.

A point of pride in the Disney heritage is Walt Disney’s cabal of pseudonyms he used to buy up black water swamps surrounding Lake Buena Vista on the cheap for his East Coast Disneyland. The plot was foiled when snooping local reporters exposed his identity (Disney purchased the remaining acreage at a much steeper cost), but the scandal has been memorialized as a ‘mystifying’ period of Disney history in various window panes on Main Street U.S.A. and as a footnote in Traditions training.

Meanwhile, 21st century black residents on the west side of the aptly named Division Ave may find it harder to be enthused for Hamilton at the Walt Disney Theatre, the centerpiece of the burgeoning art scene of downtown Orlando, when their own cultural spaces are still plagued by chronic poverty. It only takes a simple Google search to pull hits on this aspect of regional history, which includes the Ocoee Massacre of 1920. An estimated 50 to 60 black citizens were slain and the remaining estimated 500 expelled, not to return until the 1980s (a decade after the Magic Kingdom opened).

Urban legends and colloquialisms surround these tragedies. Neighborhoods come to be labeled by unkind portmanteaus, signaling what heinous crimes took place there. Sometimes these brands do just as much to attract as to repel. Activity at the intersection of S Orange Ave and Kaley Street didn’t peak prior to at least 10pm before the slaughter at Pulse in June 2016. Now, the site attracts hundreds of visitors daily. Diaspora of the local (especially brown) LGBTQ scene look for rainbow heart stickers in the corners of business fronts to determine where they will or won’t be welcomed.

The chain link fence bordering outsiders from the crime scene at Pulse is a living art gallery for memorials, tributes, devotionals, photographs, sculpture and food for our fallen. Occasionally, the Orange County Regional History Center claims some of these offerings to preserve in their archives. Will they display them again someday? Will they be represented as they were originally displayed—on a mural?

Murals, such as those professionally ordained in Mills 50, as well as those that run rogue along Ronald Reagan Blvd, may be the most prominent, public, and numerous displays of art in Central Florida. Their subjects range and aren’t always uniquely fixated on the recently deceased or the plight of perseverance, but they are all the spritely shadows to the high-rise billboards that line the highways and advertise the sirens’ artifice. They’re only seen by those who choose to traverse the capillaries of the Greater Orlando area. They’re for locals only.

Beautifully written

Don’t lie Florida is a freaking tourist trap and a horrible place to live unless your retired.