Wanda Raimundi-Ortiz was born in the Bronx and raised by a Puerto Rican mother and father. Naming herself a ‘Nuyorican’, she has struggled with her identity as a first-generation American born into a country founded on immigrants. She is a walking contradiction in her struggle to discover herself in a society with predetermined categories. Unsure what group to include herself in, she uses art as means to challenge these labels.

Despite traditional training in painting and drawing, Raimundi-Ortiz is best known for her performance and interactive art. As an award-winning interdisciplinary artist, she has created works through means of video, installation, spoken word, and performance art. She discovered that she needed to express her thoughts and beliefs through means that outstretched a simple canvas. Craving a larger outlet for her creative overflow, she turned to this technique as a better conduit for her artistic energy.

Can you describe your artistic process?

My work is really grounded in storytelling. There is a story that needs telling, and I work on finding a way that tells that story in a unique way. Can I move bodies around a room? Can I challenge the viewer with their own expectations/biases? Can I use a popular art method in an unexpected way? Much of my ‘studio time’ is spent watching people, thinking of how they move and behave. I pay attention to my experiences and try to find ways to make a very personal thing relatable to others… the challenge is in keeping the process exciting and fresh for myself. How do I make this a personal challenge? How do I keep my ideas and work creatively relevant for audiences? Where do I draw the line? Where do I cross it? I am also interested in art as activism, a platform to have uncomfortable discussions about otherness. The source of my work is my own experience being a misfit Other (as most of us are) and navigating that landscape of Puerto Rican, American, academic, artist, trouble maker, observer, Bronx chick transplant, code-switcher, culture conduit. Since most misfits are charged with the task of teaching about their otherness (whether we want to or not) I use the work as a multi-purpose tool.

Did your interest in performance art come after your training as a painter and drawer? Or did both methods simultaneously grow? What got you into performance art?

I was primarily trained in drawing and illustration. Performance happened when I, Wanda Raimundi-Ortiz, simply could no longer keep up with drawing as a way to tell my stories. I was introduced to performance art at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 2002. It became a much sharper, precise vehicle for me to express my thoughts and concepts. I was drawn to the immediacy of the medium, the direct call and response with the audience, the limitlessness of the practice. Not an actor, but a performative presentation—actions created to spark discourse, piss a few people off? Blur lines between truths? Destabilize viewers and tip their reality a bit? Part social experimenter, part shaman, part trickster… these are the things that keep me engaged in the practice.

As a professor at UCF, how is teaching art to other artists?

I enjoy teaching other artists. I enjoy pushing them beyond their chosen skill set. I invite them to challenge themselves to dig deeper for inspiration, push harder than their own expectations. I look at it less like teaching and more like coaching. If the talent and drive are there, my job is to refine it and pay forward what was given to me.

Favorite project worked on?

That is hard because I’ve loved my work (almost equally). I am certainly loving the Queens that I have been working on, but I had a great time working on the Ask Chuleta series. That was a real hoot.

Can you elaborate more on the story behind Wepa Woman? Is she still an ongoing story?

I haven’t written or created many Wepa Woman stories these days. Mainly my attention to my identity has shifted greatly since I left New York and I feel that she was a direct line to my life back there. Wepa Woman and Chuleta Bitch were the key players in my comic inspired by my life in the Bronx. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was already investigating otherness within my community as a young artist with ideas and expressions that defied the expectations of my surroundings. Raised to be very proud of my Puerto Rican heritage and somewhat self-righteous conduct, I was a rebellious goody two-shoes in goth makeup and leather, politicized in college about colonized mentalities and angry about “thugged out” lifestyles and expressions that I felt, at the time, set the Latino struggle backward. However, I was also personally struggling with the stereotypes of my culture that I failed to meet. I wasn’t Puerto Rican looking enough and was ostracized, called out, or ignored in my neighborhood. I was too ethnic to feel included by white kids at school. Wepa Woman spoke my thoughts but looked nothing like me. Chuleta looked more like me but spoke as the voice of the life I rebelled against. My life is different here, much more layered and complex, as an academic, working professional artist. I am older, more introspective. Didn’t expect these things to affect my process as much as it has. I have been flirting with revisiting the characters and bringing them up to speed with my own life changes and experiences.

You mentioned that it is loosely autobiographical work—how much of Wanda Raimundi-Ortiz yourself shines through this character?

Honestly, all of my work is loosely autobiographical. Wepa Woman and the other characters in the stories were versions of my personality: multiple voices, ideologies, clashing concepts of self, culture, accountability, community. It is where I worked out (and uncovered) the nuances of the politics of my multiple identities. I was able to pull each persona out and develop them individually. I guess I still do that now, with the queens, in a much more elaborate way. The work is where I try to figure stuff out—power dynamics, external influences, internal dilemmas. Art making is how I try to make sense of the world(s) that I live in.

You currently have a show running at the Cornell Fine Arts Museum, Displacement: Symbols and Journeys. Could you elaborate more on the show and what works you have included?

I have one work in the Displacement show… a drawing of my mother as the Queen Mother. She is the epitome of displacement and resilience. She arrived in this country in the 50’s with a small baby and another on the way, 20 years old and unable to read or write. Somehow she and my dad managed to raise seven children on one Puerto Rican man’s wages. She got us up and ready for school, pushed us to excel. There are now four women in my family that hold master’s degrees. She pushed herself to learn how to read at the age of 60 or so. The catalog where her portrait is published is a book she can now read on her own.

Her existence and resilience is why I do what I do. I cannot imagine having language as the ultimate barrier, that her story never be told or recorded, that a life as amazing as hers be erased if not documented. In my drawing, she is wearing a crown made just for her. Without her, there would be no me, no art, no queens, no court. She IS the Queen Mother. My success as a professional is evidence of her presence on this earth.

Do you have anything in the works at the moment?

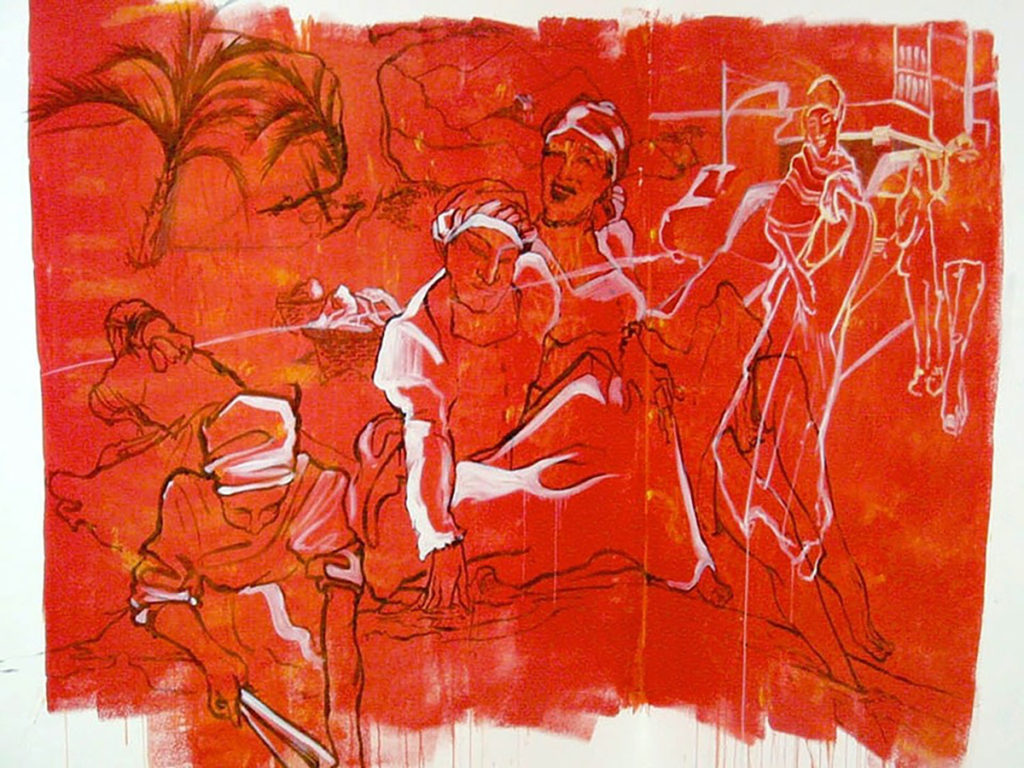

I have several irons in the coals right now. I am currently showing several drawings of key women in my life at the Cornell Fine Art Museum at Rollins College and at the American University’s Katzen Art Center in Washington DC. This body of queen drawings are of women that have been important to my growth as a woman, as a ‘queen’. They are the Royal Court—where I, as a woman and creator, have been groomed and cultivated, where I draw my courage, where I go for wisdom, comfort, support, rejuvenation. These drawings are where I have spent the bulk of my summer and will spend the next year or so. Along with another very intimate performance and a memorial created for the victims of the Pulse tragedy here in Orlando. I am also preparing for a solo show at Longwood Art Gallery in New York.

What is your dream project?

I just saw the catalog of my life before my eyes. My dream project would be to have all the narratives that have woven throughout my career be laid out in a Wanda Raimundi-Ortiz show/book format. Almost like a huge exhibition with a corresponding catalog.

But that isn’t really a project; those are life goals. I have wanted to connect with women that are survivors of various kinds of abuse and help them create royal archetypes for themselves. [I want to] help [them] reenvision themselves as true queens, survivors, warrior women, empresses… I would like to empower them with art the way art has given me voice and strength to unpack my issues, look at them, understand them, work through them, and emerge victoriously as a result. Yeah, that is my dream project. I would like that very much, indeed.

As a creative activist, Raimundi-Ortiz uses her artistic expression as a means to generate a message. Whether it be personal or universal, she likes to create a discussion that causes her audience to really think about themselves and the world around them. Questioning preordained commonalities within our society, along with searching for new truths in oneself, Raimundi-Ortiz uses everything as inspiration. Much can be discovered about oneself through others. She hopes that when people listen to her narrative, they will learn new things about themselves. And in turn, she will gain new insight into those around her.

She understands that not everyone fits into neat little boxes, but rather they far outstretch any means of categorization. Growing up as a Hispanic woman in the Bronx, she struggled with finding herself and where she fit into the larger community. She explains that she was “not light enough to be included in the mainstream of ‘gringolandia’ or the Anglo world, and not dark enough to belong in the black community.” Since learning to embrace uniqueness, Raimundi-Ortiz now uses her ‘otherness’ as a tool throughout her art, much like a painter would a brush.

You can see more at:

WandaRaimundi-Ortiz.com

One thought on “Wanda Raimundi-Ortiz”

Comments are closed.